Then & Now | Extradition: how Hong Kong and Macau have provided China with ‘a sunny place for shady people’

- The absence of extradition agreements between Hong Kong, Macau, mainland China and Taiwan have made them safe havens for the corrupt and the criminal

Extradition arrangements with Macau, mainland China and Taiwan – or, rather, the convenient lack of them – have long been one of Hong Kong’s most curious legal anomalies. Legislative proposals to extend the scope for rendition between these jurisdictions have been controversial, with various groups raising concerns.

Macau and Hong Kong never formally cemented joint extradition arrangements when they were, respectively, Portuguese and British colonial territories, though low-key renditions were known to occasionally occur. The reasons for this curiosity are ultimately tied up in the fact that both territories have long provided Greater China with, as British author W. Somerset Maugham once shrewdly noted of the French Riviera, “a sunny place for shady people”. This jurisdictional no-man’s land was especially useful during the cold-war era, when the colonies provided safe havens for intelligence agents to operate in.

Since the Portuguese handover of Macau, in 1999, agonisingly slow attempts to regularise relations between what are now separate administrative areas within the same nation state have been ongoing.

The absence of formal extradition arrangements with the mainland ensured that the crooked merely needed to cross the frontier, either way, to be safely beyond the reach of the law. Or at least they were so long as the authorities on the other side were prepared to shield them. Historically, this state of affairs had convenient advantages.

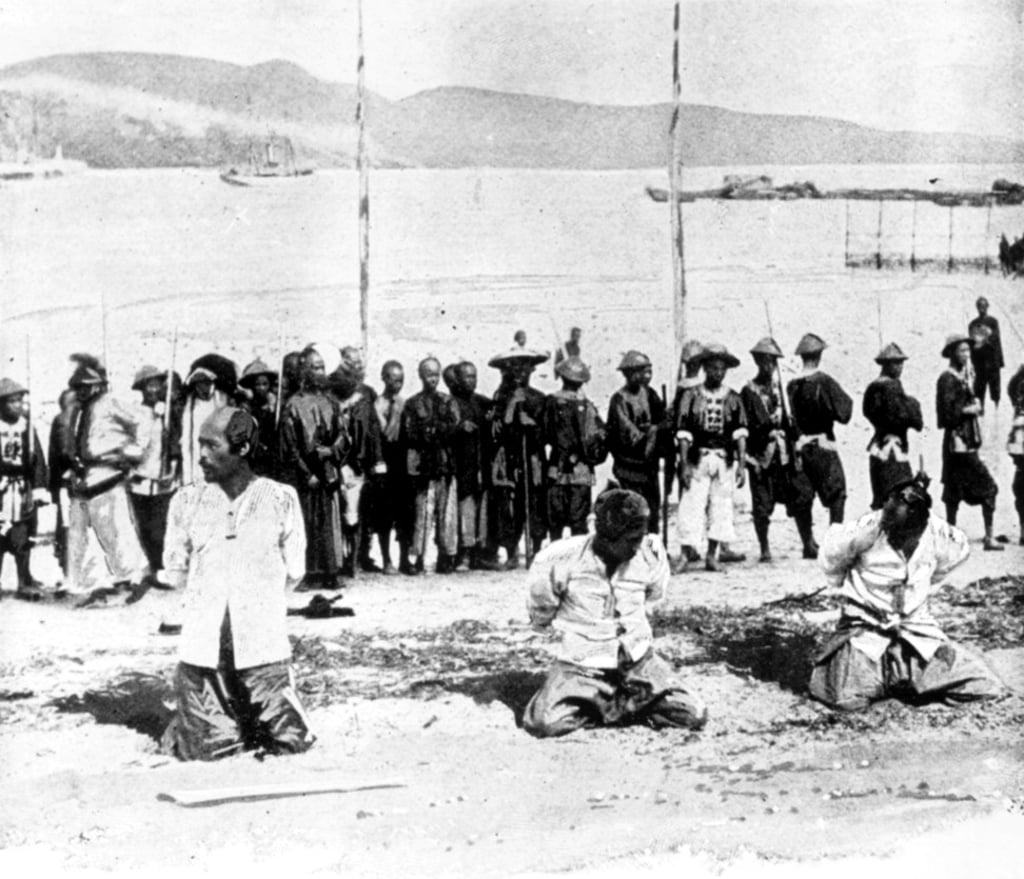

Until the New Territories lease was signed, in 1898, and this particular loophole was plugged, pirates and other bandits who could not be convicted in Hong Kong courts due to rule of law considerations were typically deported – after their acquittal and discharge – across the harbour to the Kowloon Walled City. Forewarned, the Chinese magistrate stationed there – with no further real judicial process – swiftly arranged for the separation of head from shoulders with a broadsword, dispatching the legally (if not actually) innocent criminals to the next world for final judgement.