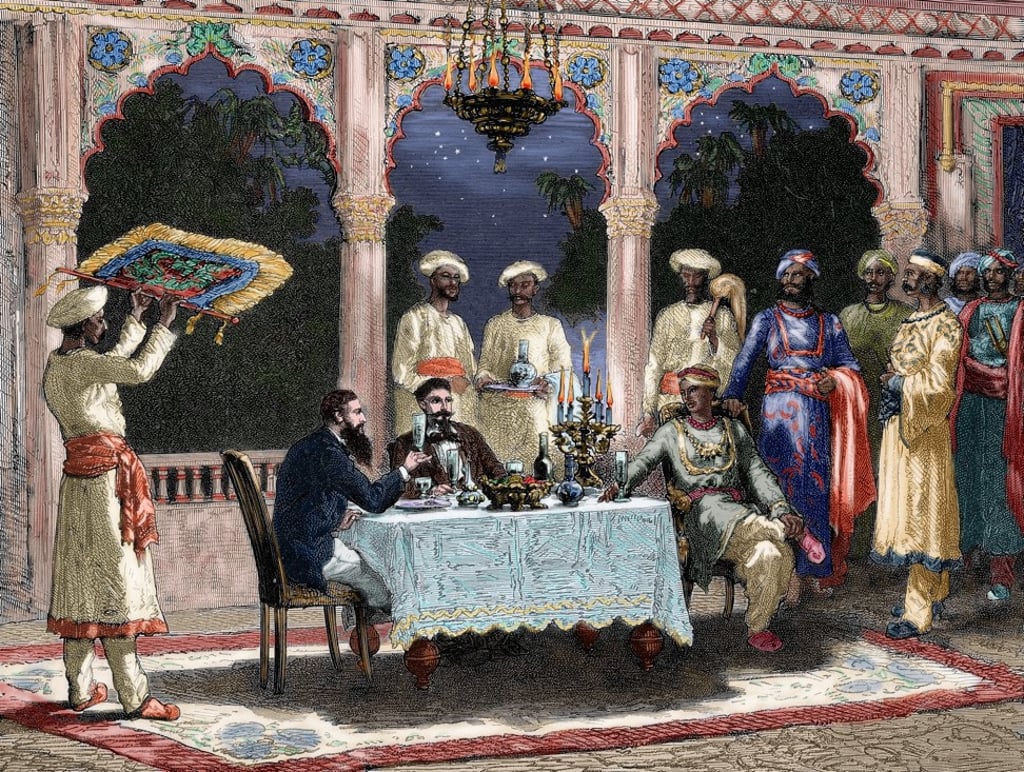

Then & Now | Why elegant dinner tables of colonial times were laden with tinned food

A lack of fresh produce as well as hygiene concerns meant most meals were made from processed imported foodstuffs that would then be jazzed up with chutneys, mustard, pickles and any manner of relish

How was the diet of colonials distinct from that of their contemporaries at home? Freshness – or the lack of it – was a key difference. From the late 19th century onwards, most European foodstuffs consumed in colonial contexts – from India and Southeast Asia to China and the Pacific – came in tins. While some fresh foods were simply unprocurable locally, preventive hygiene was the main reason for this. Microbiology discoveries during this period conclusively proved the links between certain food-borne pathogens and the often-fatal diseases they caused. Effective cures were decades away, and prevention was regarded as the only way to maintain one’s health in habitually filthy, frequently primitive tropical conditions. Tinned food – as long as the can itself remained intact – was germ-free, and therefore safe to eat.

Constant attention to hygiene was essential; various guidebooks intended for colonial wives stressed the importance of making periodic kitchen inspections, but recommended a scheduled visit once a week only, with reliance on trust, and a cautious weather eye, the rest of the time. Not everyone listened; a period memoir staple were tales of over-fussy, carbolic-mad housewives who harassed their staff to the point where “cookie” and the other servants eventually resigned en masse.

Inevitably, taste was sacrificed to safety by the canning process. In consequence, another variety of preserved foods became essential additions to colonial tables; prepared mustard, mint jelly, Worcestershire sauce, chutneys, ketchups, pickles and relishes of various kinds all helped ring the changes on a drab, unvarying diet. What was actually served up for the evening meal in a married quarter in Hong Kong, Fiji or Malaya in 1935 differed little from what might have been on the menu in Leeds, Cheltenham or Bournemouth at that point in history; in Britain, however, potatoes and other root vegetables, along with peas, beans and asparagus, would have been fresh in season, and the milk would come fresh in a glass bottle, instead of evaporated in a tin.

Processed cheese, either foil-packaged or canned, was another British colonial food staple – like tinned butter, processed cheese could tolerate prolonged periods without refrigeration. Dutch colonies, by contrast, imported large quantities of wax-sealed edam, gouda or leiden cheeses, which also lasted well in the tropics.

Most alcohol consumed in colonial society was hard liquor, either served neat over ice, or diluted with various mixers – whisky-soda, gin and tonic and that most colonial drink of all, BGA (brandy and ginger-ale) predominated. Copious quantities of well-chilled beer and locally brewed stout – the latter was more popular in Singapore and Malaya – dominated colonial drinks tables.