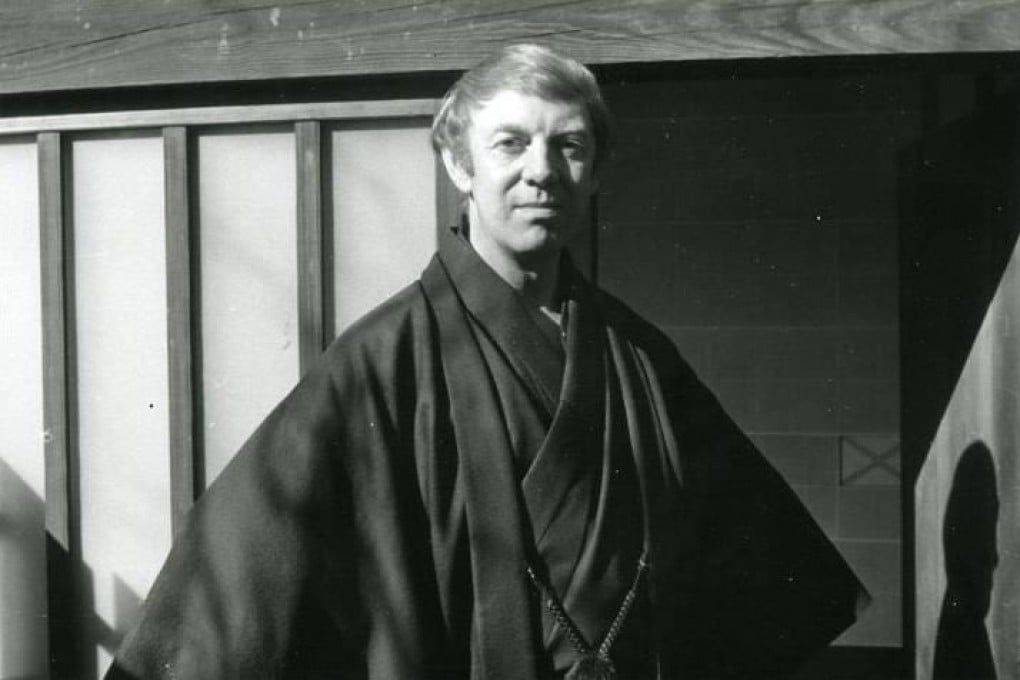

Then & Now | Writer of blasphemous homoerotic poem, James Kirkup’s desire to shock extended to Asia

The prolific British writer, who spent three decades in Japan as well as a brief period in Hong Kong, is infamous for the poem behind the last successful prosecution for blasphemy in Britain – The Love that Dares to Speak Its Name

Prolific British poet and travel writer James Kirkup is best remembered for a single poem – The Love that Dares to Speak Its Name – the 1976 publication of which caused the last successful prosecution for blasphemous libel in Britain. In the poem, a Roman legionnaire fantasises about having sex with the crucified Christ, and suggests Jesus had counted John the Baptist, several disciples and, less plausibly, Pontius Pilate among his sexual partners. After the poem was published, in Gay News, the British paper was prosecuted and fined, and its editor handed a suspended sentence.

This controversial legal action was brought by Mary Whitehouse, the British teacher-turned-moral crusader whose shrill but well-meaning denunciations of “obscenity” made her a polarising figure from the 1960s to her death, in 2001. Pursed-lipped disapproval of sex and bad language – the BBC and its long-serving director general, Hugh Greene, were particular targets – obscured her more positive campaigns. Vulgarities that have descended into everyday speech – “bloody”, “bugger” – would see Whitehouse appear on the box, pop-eyed and indignant.

The trial judge described the poem as “quite appalling”, a verdict echoed by various literary critics; one described it as “an awkward mixture of homoeroticism and English hymnal”. Even the author later distanced himself from it. Nevertheless, the desire to shock was a key aspect of Kirkup’s temperament; an earlier poem, The Drain, explores his delight at watching strapping young workmen wield “well-oiled tools”. Unsurprisingly, mid-1950s Britain did not suit him. Decades of expatriate wandering followed, mostly in Asia.

Tropic Temper: A Memoir of Malaya (1965) grew out of a short-lived stint as an English lecturer at the “utterly third-rate” University of Malaya, and his travels around the newly independent country. Kirkup’s languid description of life in Kuala Lumpur, then a small-town capital, is sharply drawn, with acidulous remarks about academic mediocrity, racial animosity and professional and personal college rivalries. Judging by the sour reviews from his erstwhile colleagues, Kirkup’s liverish observations were probably accurate.