Colonial Hong Kong’s ‘creative’ approach to lending to ex-China shipowners

While tycoons cried racism, their ships were breaking the UN embargo on trading with China – and their mainland families were under threat

Solid, cross-checked, independently sourced facts and equally solid, broad-based interpretations drawn from them are the gold standard for any historical writing. A challenge with corporate memoirs – and company histories – is that an author’s claims about the past tend to go unchallenged, with few external filters to mitigate errors. After all, apologists maintain, it is their version of events, so who can gainsay them?

This flaccid approach is especially prevalent in Hong Kong, where whatever dribbles forth from the chairman’s lips – especially in his later years – is uncritically licked up by those whose living depends on humouring him. There has never been a shortage of underemployed, ethically flexible hacks prepared to bash out a “history” or “biography” for the right price, with no inconvenient questions asked. And so the line between historical facts and self-serving corporate fantasies blur even further.

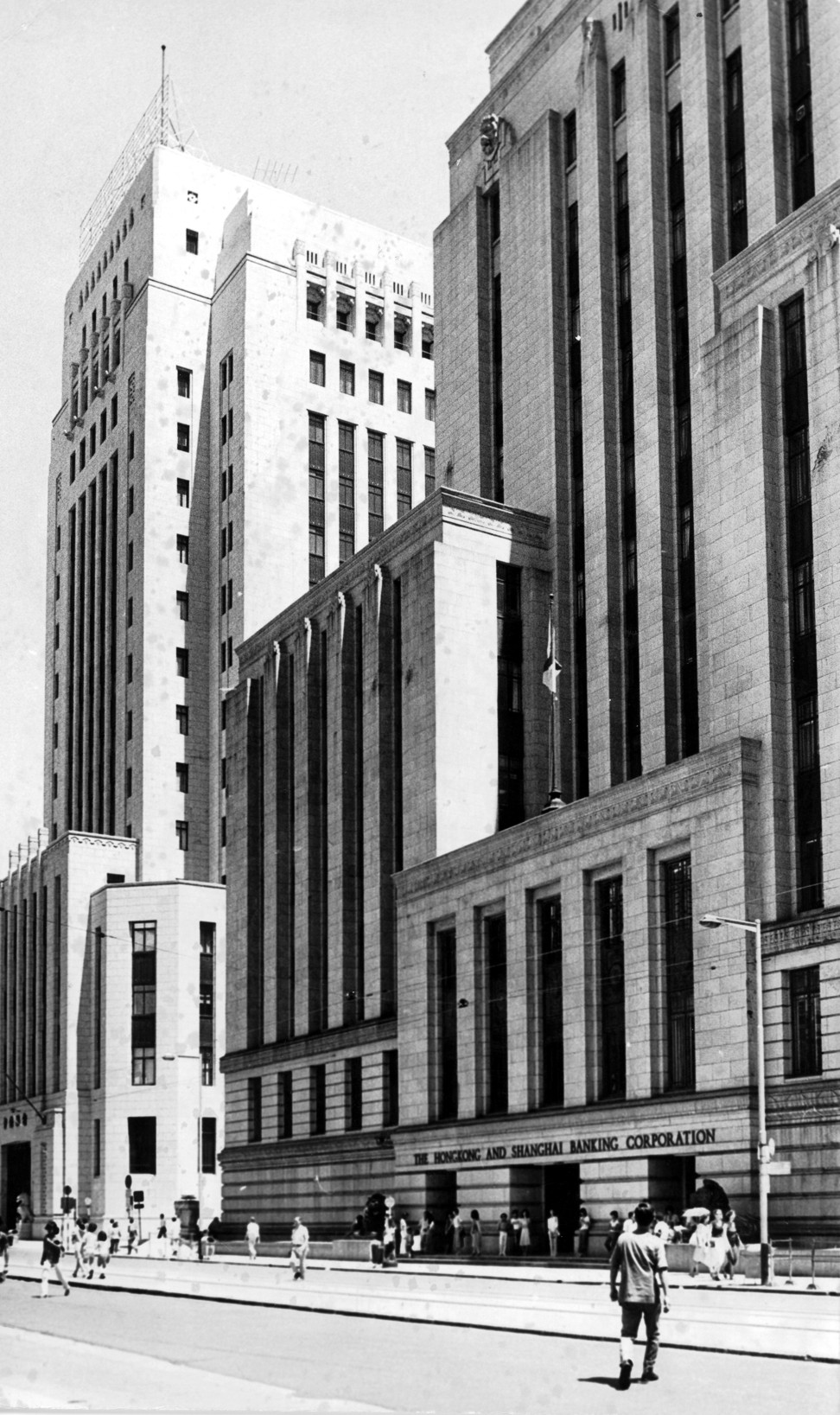

One recurrent whine in Chinese tycoons’ memoirs is the difficulties allegedly faced in the 1950s when seeking direct finance in Hong Kong, especially from mainstream local banks HSBC and Standard Chartered.

All too often, such complications were sourly attributed to Western racism. Petulant grumbles about colonial arrogance, while seldom completely unfounded, deflect attention from the reasons for institutional reluctance to deal with them directly. Such hesitancy was coldly pragmatic in origin, not racial.

During the cold war, local banks with significant exposure to the United States were reluctant to loan money directly to anyone whose broader political connections they could not vouch for. This was critical during the heyday of the United Nations’ embargo on direct China trade, which followed the outbreak of the Korean war, in 1950.

These strictures particularly involved Chinese shipowners, many of whom were one-time Shanghai businessmen who had left China as the Nationalist government imploded, in 1948-49, yet remained exposed to events on the mainland as the communist regime consolidated power.

With the personal safety of immediate family members in China intrinsically linked to how cooperative their relatives outside China were with the regime, some “running with the hares and hunting with the hounds” was inevitable.

What Hong Kong leadership can learn from 1922 seamen’s strike

Using their ships to help evade coastal blockades enabled shipowners to burnish their “patriotic” credentials. And the sizeable profits to be made from transporting embargoed materials – in particular high-grade steel, rubber, petroleum products, pharmaceuticals (especially antibiotics), aircraft parts and other highly engineered industrial items – made the risks worth taking. It also made the shipowners toxic to mainstream banks. “Know your customer” protocols meant extra due diligence was vital with many ex-China clients, notably the shipping fraternity.