Then & Now | Hong Kong now has its own ‘Five O’Clock Follies’ media cabaret as press briefings stretch public credulity beyond breaking point

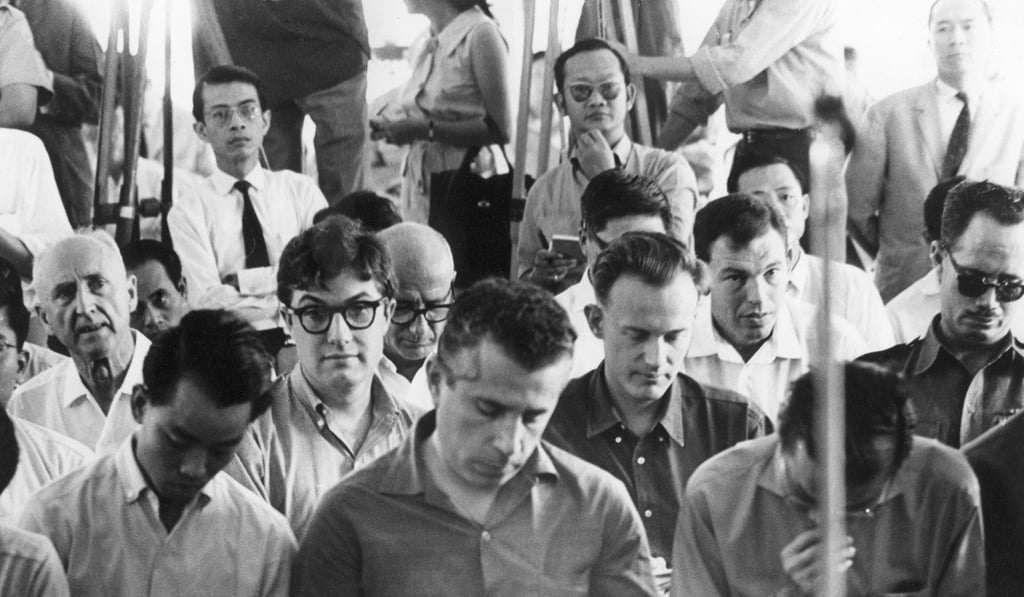

- During the Vietnam war, regular press conferences were held at the roof terrace bar in Saigon’s Rex Hotel when a breakdown of the day’s hostilities, casualties and ‘successes’ were given

- Richard Pyle, then the Associated Press bureau chief, described it as “the longest-playing tragicomedy in Southeast Asia’s theatre of the absurd”

Richard Pyle, the Associated Press bureau chief, memorably described the proceedings as “the longest-playing tragicomedy in Southeast Asia’s theatre of the absurd”. Press pack feeding frenzies anywhere, as numerous foreign correspondents’ memoirs make plain, relied as heavily on interviewing each other for “background” as on quotes from key figures. It was ever thus, but in Vietnam, the scale of official dissembling was remarkable.

People who had not been anywhere near the action vividly described eyewitness accounts related by sweaty, dirt-stained journalists and news cameramen returning from the field. Yawning chasms loomed between the public relations rendition of events and the full Technicolor accounts of those who had been at the scene. Corrosive cynicism became inevitable, and only worsened as the intractable Vietnam conflict bogged down. So it is in Hong Kong, half a century later.