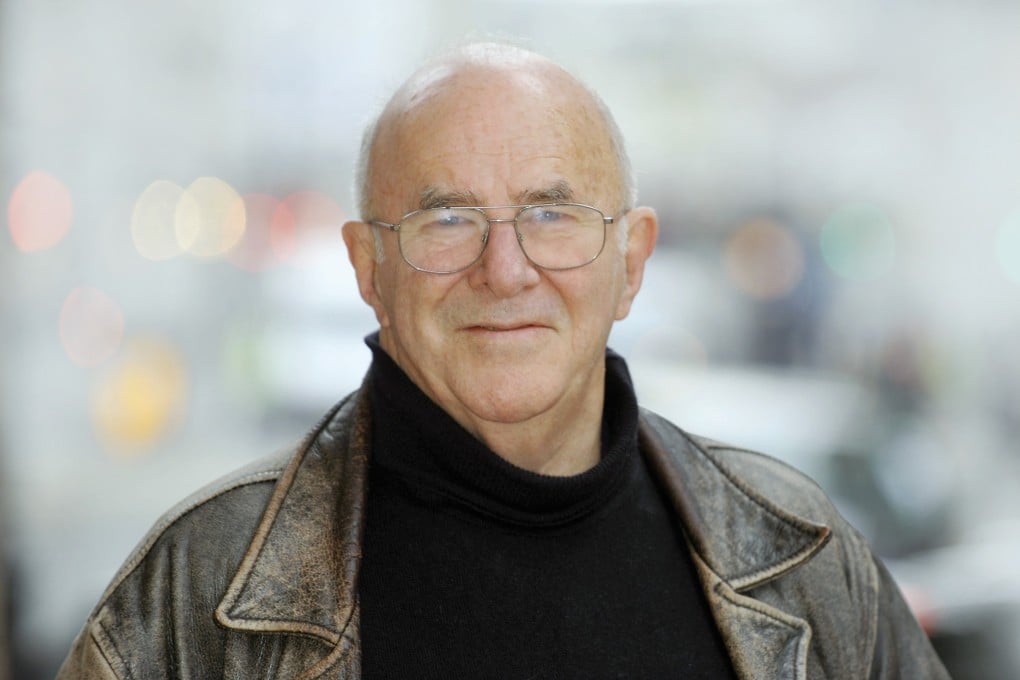

Then & Now | How Clive James’ Hong Kong connection inspired his poetry and leaving Australia allowed him to flourish

The late writer and presenter’s father, a one-time Japanese POW, is buried in Sai Wan Bay.

In the late 1940s, the remains of those who had died in Taiwan were exhumed and relocated to Hong Kong; following the Chinese civil war and the communist assumption of power on the mainland in 1949, war graves located in a British territory were considered more secure.

James survived the Japanese prison camps, but tragically died in September 1945, when the American B-24 transport aircraft on which he and other recently liberated POWs were travelling from Okinawa to Manila, in the Philippines, was diverted owing to a typhoon and crash-landed in Taiwan. Clive James wrote a moving poem, My Father Before Me (2004), partially quoted below, on visiting his father’s Hong Kong gravesite.

This hillside, since I visited it first,