Then & Now | He defended Ho Chi Minh and worked with Lee Kuan Yew: how one London barrister changed history in colonial era

- It is not unusual for British barristers to parachute into Hong Kong to take on controversial cases

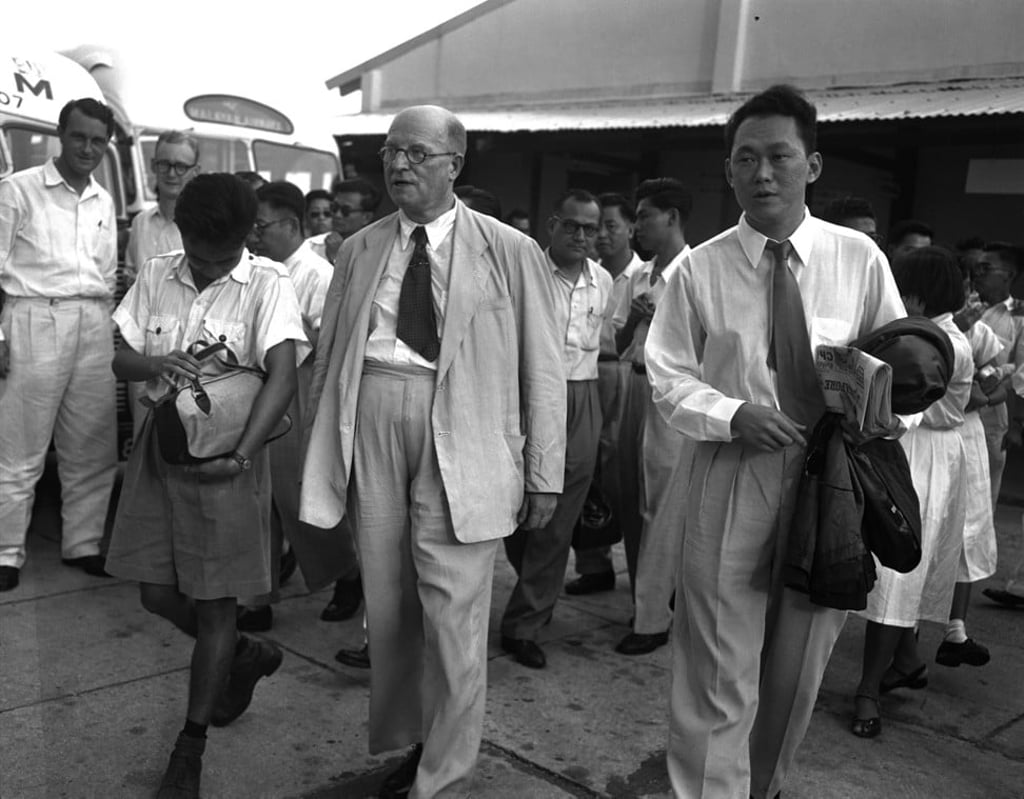

- Indeed, some high-profile lawyers like Denis Pritt made their names defending complex and politically charged cases

Every so often, prominent British barristers parachute into Hong Kong to take on controversial cases allegedly too complex for local silks. Sometimes these cases are such that an outside practitioner may offer fresh perspectives. Overseas barristers are extremely well paid for their services, so it is no surprise that, for decades, Hong Kong has been wryly termed “Treasure Island” by outsiders given leave to appear before the local courts.

Given the inevitable expense, the more overseas barristers that are employed the more “face” is gained, which can be a compelling consideration in Hong Kong. In high-profile cases where, let’s face it, the accused may be culpable of even more naughtiness than the offences with which they have been charged, the more top-flight representation they can call on, the better.

As one retired senior judge remarked to me during a conversation about a recent high-profile corporate corruption case that had engaged several London silks – and nevertheless ended in a brace of convictions and lengthy prison sentences – “just how guilty does one have to be to go to all that effort?”

Some top London barristers made their names defending complex and politically motivated cases around the world. One such individual, whose early socialist leanings eventually turned him into a crypto-communist, was British barrister Denis Pritt (1887-1972). Pritt had been a Labour Party member since 1918 and, according to one contemporary, “he swallowed it whole” after a visit to the Soviet Union in 1932. He became such a communist sympathiser that he was later expelled from the Labour Party.

A document prepared by English novelist George Orwell for the Information Research Department in 1949, and made public only in 2003, listed the names of likely communists within the British establishment. In it, Orwell noted Pritt was “very able and courageous” as well as “almost certainly an under-ground Communist”.