Reflections | Chinese emperors might not have faced impeachment, but they were not immune to removal from rule

- The power of rulers in imperial China was absolute, but they were still at risk of being overthrown by adversaries

- Liu He’s behaviour did little to endear him to his ministers, who deposed the new emperor after just 27 days

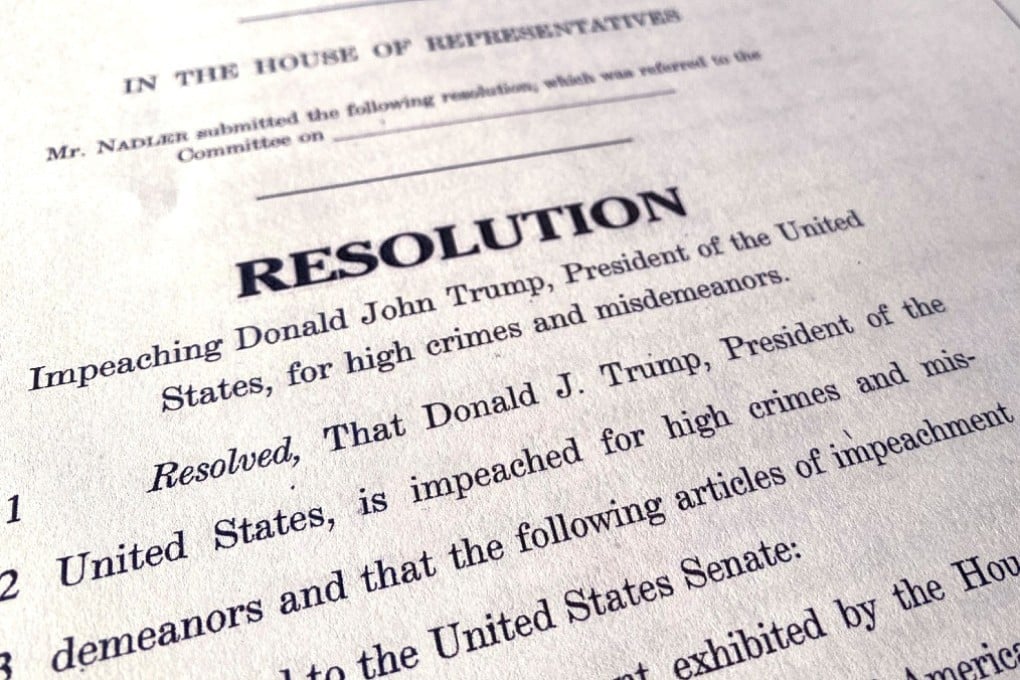

By now, many will be familiar with the part of the American constitution that provides for the removal of the president “on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors [sic]”.

Liu He (92–59BC) was the nephew of Emperor Zhao of the Western Han dynasty, who died in 74BC at the age of 21 without any children. The formidable Huo Guang, a powerful minister who dominated the government after Zhao’s death, reckoned that among the male members of the imperial clan, Liu was the most amenable to his control. He arranged for Liu to be “adopted” as the late emperor’s son (though he was only two years younger than Zhao) and formally installed him as emperor.

Upon arriving at the capital from his fiefdom Changyi (present-day Shandong), the new emperor did not endear himself to Huo. Not only did Liu harass the bureaucracy by issuing an average of 40 orders a day, but, most shockingly, he bedded the consorts of the late Zhao, who were, strictly speaking, his aunts and adoptive mothers. Zhao’s widow, the young Empress Dowager Shangguan, appealed to Huo for help to rid the palace of this lout.

Before the ministers at court one summer’s day, in 74BC, Huo read out charges against Liu and declared him unfit for the role of emperor. Huo personally removed Liu’s crown, before placing him under house arrest. Liu was emperor for only 27 days before he was deposed.