Then & Now | Who were the lascars, where did they come from and where have they gone?

- Muslim seamen from around Asia, many of them stereotypical drunken sailors, are remembered in Hong Kong road names

- Bangladeshi and Indonesian crew still sail the high seas, although the archaic term has fallen from favour

Lascars appear in almost every Asia-themed travel account and shipping memoir, from the mid-19th century advent of steamships until scheduled passenger sailings from Europe finally succumbed to competition from air travel in the late 1960s. But who were the lascars, where did they come from and where have they gone?

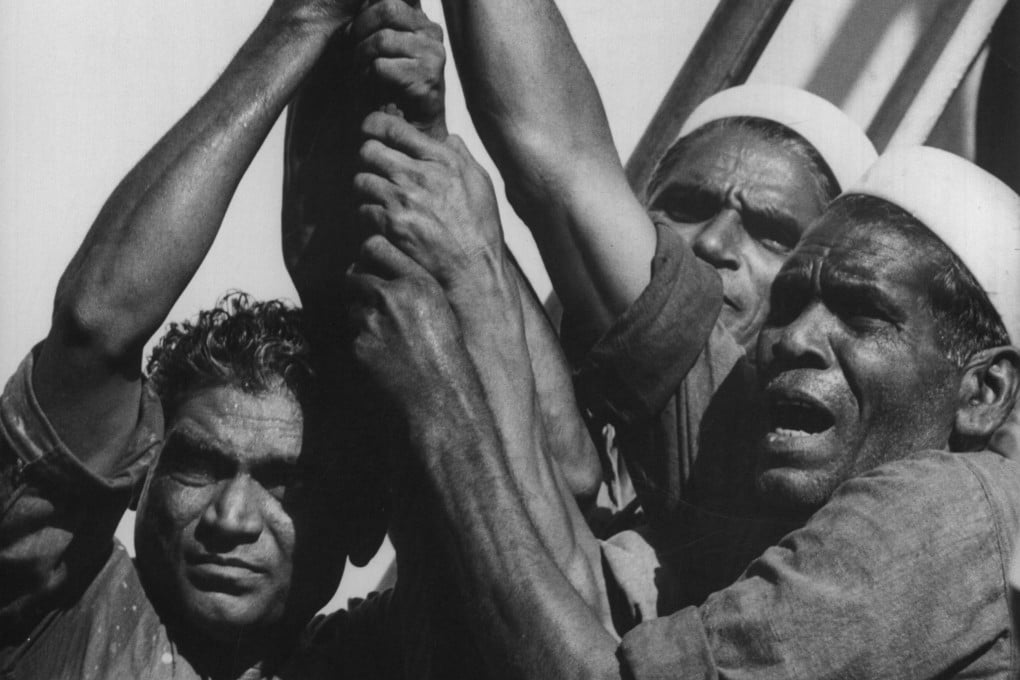

Broadly speaking, the term was a generic one for Muslim merchant seamen. Usually Bengali, these men were mostly recruited from Calcutta, Dacca, Chittagong and Cox’s Bazar. Others were engaged from much further west. Aden, the British-ruled Red Sea coaling station, also supplied “lascars”, most of whom were Yemeni sailors.

Some intercontinental shipping lines, notably P&O, exclusively employed lascars as deck and engine room crews. Other shipping lines that passed through South or Southeast Asian ports, such as the Glen Line, employed lascars as well as Chinese crewmen for certain roles such as cooks, laundrymen and stewards.

Dutch shipping company Java-China-Japan Line, which became Royal Inter Ocean Lines after the war, employed its own brand of “lascars” recruited from Indonesian ports such as Surabaya and Makassar. Mostly Javanese, these Indonesian “lascars” also included a significant contingent of Bugis and other ethnic groups with strong maritime traditions.

A perennial management challenge, despite the Islamic prohibition on alcohol, was the lascars’ tendency to enjoy drunken binges on shore. For this reason, some shipping companies engaged only Chinese seamen. These included the Blue Funnel Line, which plied ports between Liverpool and Japan, with a subsidiary route to Australia. Its founder, Alfred Holt, a deeply religious teetotaller, preferred Chinese employees for their tendency not to hit the bottle.