Hong Kong’s links with Korea haven’t always been as happy-go-lucky as its K-pop obsession

- The connection dates goes back to Japan’s pre-war militaristic expansion in East Asia

- Some of the most brutal guards in Hong Kong’s prison camps are now known to have been Korean

Gaggles of selfie-stick-wielding Korean tourists snap away at identical plastic cups of “Hong Kong style” milk tea outside Lan Fong Yuen, in Central, and other “local” Instagram clichés. Or at least they did, until months of unrest – and now the coronavirus outbreak – dramatically slashed arrival numbers.

While the ubiquity of Korean culture may seem new, a Korean presence in Hong Kong goes back to the time of Japanese colonialism and militaristic expansion in East Asia.Before the Pacific war, the small Korean community in Hong Kong was regarded – so far as the average resident gave it any thought at all – as barely indistinguishable from the Japanese. Korea had come under Japanese control in 1910 and Formosa (modern Taiwan) became a Japanese colony in 1895. By the 1930s, the inhabitants of both territories were seen by the wider world as colonial Japanese, in much the same way as Australians, New Zealanders and Rhodesians were broadly regarded (though not by themselves) as sort-of British.

In the manner of colonial peoples the world over, sedulously aping those in power was a reliable pathway to success in their own society. Koreans (and Formosans) who fared best in Japanese settings were those who had erased virtually all aspects of their own culture and national identity: “passing” for Japanese was among the highest (and probably the saddest) cultural compliments that could be paid to any Korean.

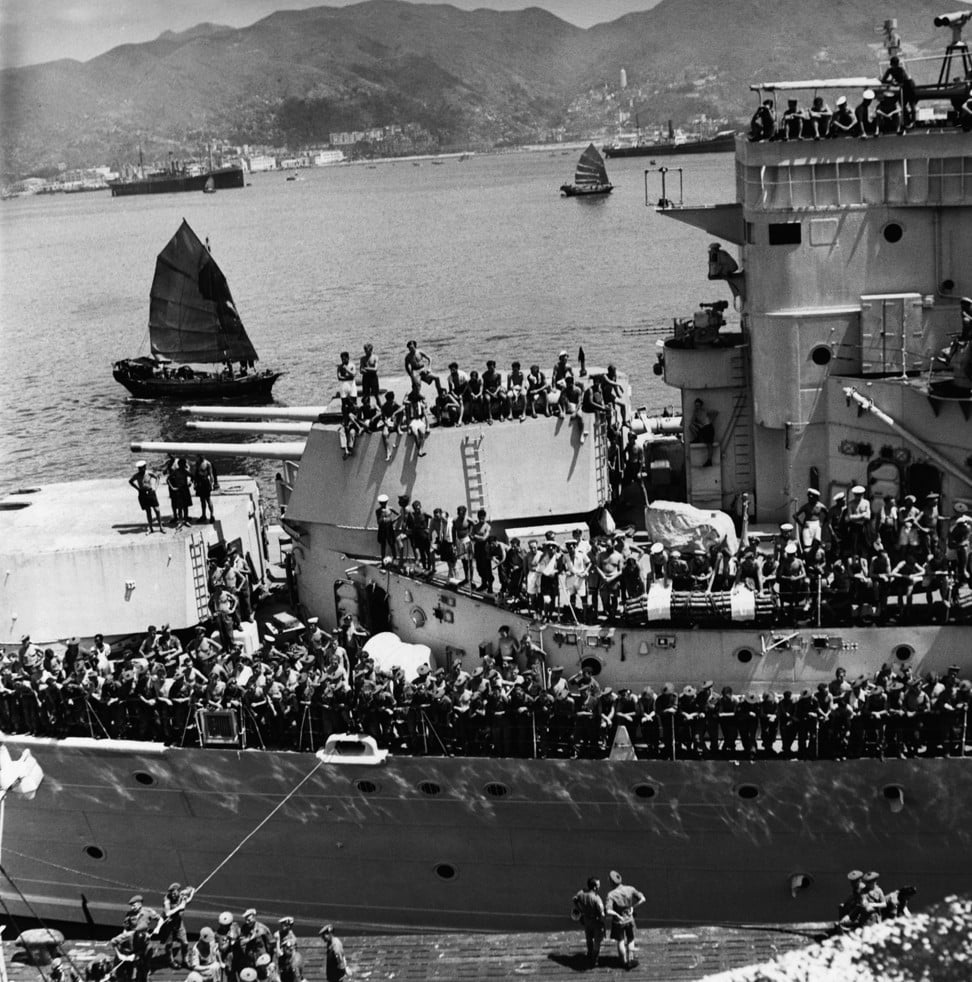

Hong Kong’s other main connection developed when the Korean war broke out, in 1950, and spluttered on until a ceasefire was brokered, in 1953. (The conflict has never officially ended and the Korean peninsula remains divided across a heavily fortified Demilitarised Zone.) During this time, Hong Kong became a key staging post for United Nations forces rotated through Korea.

The local economy boomed following a UN-led embargo on direct trade with China, imposed after the Chinese invasion of North Korea. Hong Kong’s import-export gateway role was strangled by the embargo, but local manufacturing industries rapidly expanded to fill the gap, greatly assisted by abundant refugee labour and flight capital into the colony from elsewhere in China and Southeast Asia.