Reflections | Malaysia’s latest political shenanigans have echoes in Qing dynasty China

- In late 19th-century China, the Hundred Days’ Reforms might have set the country on an entirely different path

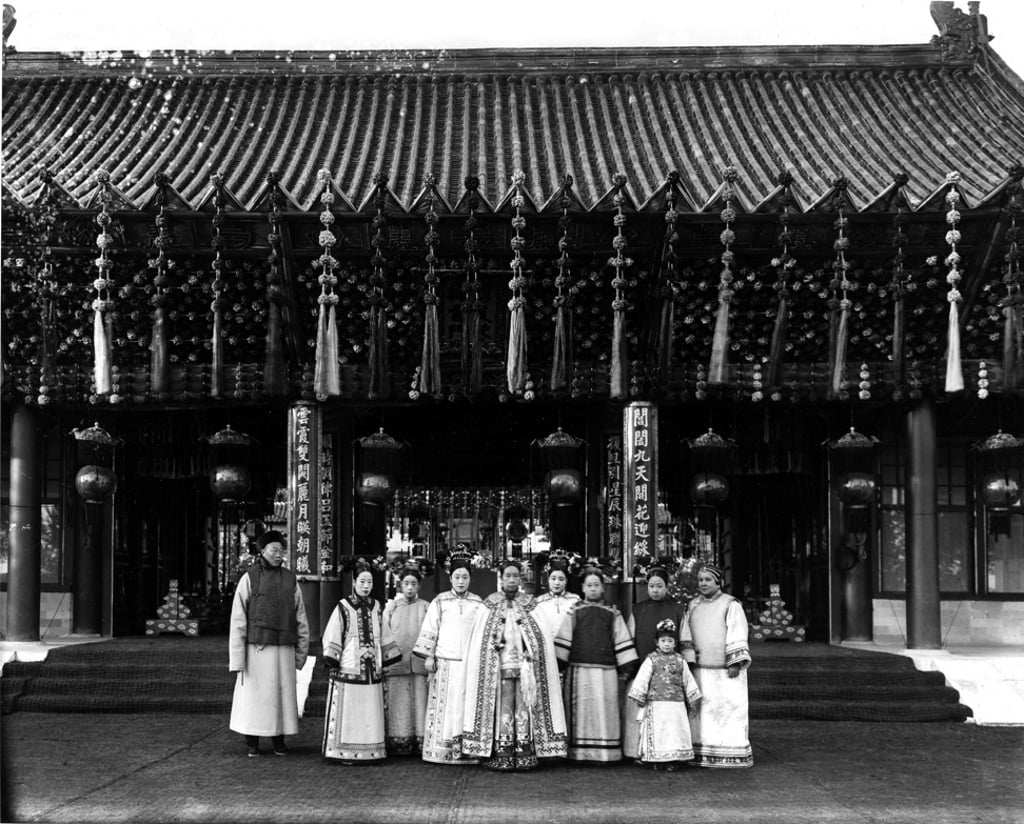

- But reformers were no match for the conservatives at court, led by Empress Dowager Cixi

Malaysia is grappling with a political quandary that is as ill-timed as it is unnecessary. I was in Kuala Lumpur last month when the series of events first started to unfold. A meeting at the national palace between the leaders of several political parties and Malaysia’s kingwas the first indication something was afoot. Then came reports of a dinner attended by more than 100 members of parliament of different political stripes. At the same time, supporters were gathering at the homes of certain party leaders. Rumours swirled of a sudden change of government.

In 1898, near the end of the imperial era, a palace intrigue forever changed the history of modern China. The Qing dynasty’s navy was decimated during the 1895 Sino-Japanese War, resulting in China ceding Taiwan to Japan. Soon afterwards, Western powers began to carve out Chinese territories: the Germans occupied present-day Qingdao; the Russians took Dalian; the French Zhanjiang, in southern Guangdong; and the British Weihai, in Shandong, as well as Kowloon and the New Territories.

Distressed and alarmed by China’s subjugation by foreign countries, a group of scholar-officials, led by Kang Youwei, petitioned the young Guangxu emperor to implement reforms to strengthen China militarily and economically, and eventually become a constitutional monarchy similar to western European countries and Japan. The so-called Hundred Days’ Reforms, as it is popularly known in the West, began in earnest on June 11, 1898.