Then & Now | Remembering Sonny Sales – a true Hong Kong patriot, 1920-2020

- Sales was a politically talented, supremely civic minded – and occasionally divisive – local legend

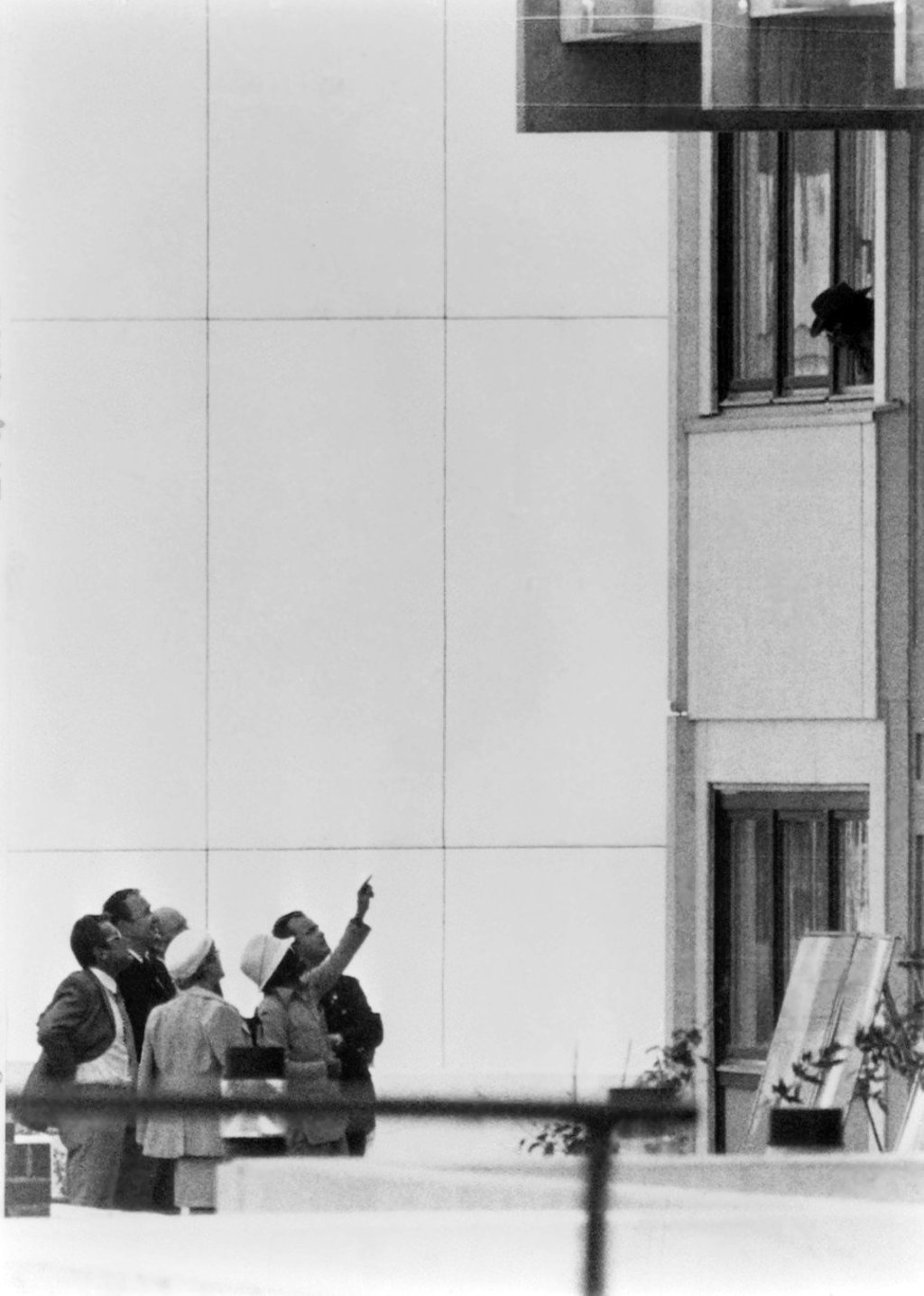

- He personally negotiated the release of Hong Kong athletes taken hostage at the 1972 Munich Olympics

Local Portuguese community leader Arnaldo de Oliveira Sales, popularly known as Sonny, who recently died aged 100, was a prominent, and intermittently polarising, figure in Hong Kong’s wider community life for more than 60 years.

Born in 1920 on Shamian, the Anglo-French concession island in Canton (Guangzhou), Sales was educated at La Salle College in Kowloon, and – like many among Hong Kong’s Portuguese community – spent the Pacific war years as a refugee in neutral Macau. He later married Edith Nolasco da Silva, an heiress and a member of one of Macau’s wealthiest Macanese families; they had no children, and she died in 2006.

Sales was an example of a type once widely found among Macanese – and Filipino – cultures; the mestizo-branco (“mixed-white”) who rose to social prominence and community influence in race-conscious colonial or semi-colonial societies. In both of these groups, those who oriented towards their Western side – and could pass for white, as Sales did – tended to reach higher positions of power and influence than those of mestizo-Asiatico (“mixed-Asian”) appearance.