Reflections | Powdered pus up the nose and other Chinese precursors to vaccinations

By the Ming dynasty, ‘variolation’ was being used to immunise against smallpox, often quite successfully

Certain countries see the development of a vaccine as a race with national prestige at stake, reminiscent of the Cold War rivalry between the United States and Soviet Union in everything from culture to sports, and from space exploration to nuclear warheads. While competition may encourage progress, imagine how much more could be achieved – and how much quicker – if data and findings were shared across national borders. It is sobering that, even in a global emergency, the notion of our shared humanity fails to trump narrow tribalism.

The first successful vaccine in modern history was the smallpox vaccine, developed by Edward Jenner in late 18th century Britain. Highly infectious and often fatal, smallpox was the scourge of the ancient world. Taoist medical practitioner Ge Hong (AD283-343) was the first Chinese writer to mention the disease, tracing its appearance in China to AD23-26.

The ancient Chinese used a method called variolation to immunise against smallpox. According to legend, a physician on Mount Emei, in Sichuan, originated the method around the 11th century and was invited to the capital, where he successfully immunised the son of the Grand Councillor. This story is probably apocryphal but we do know that, by the middle of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), prevention of smallpox by variolation was being widely practised in China.

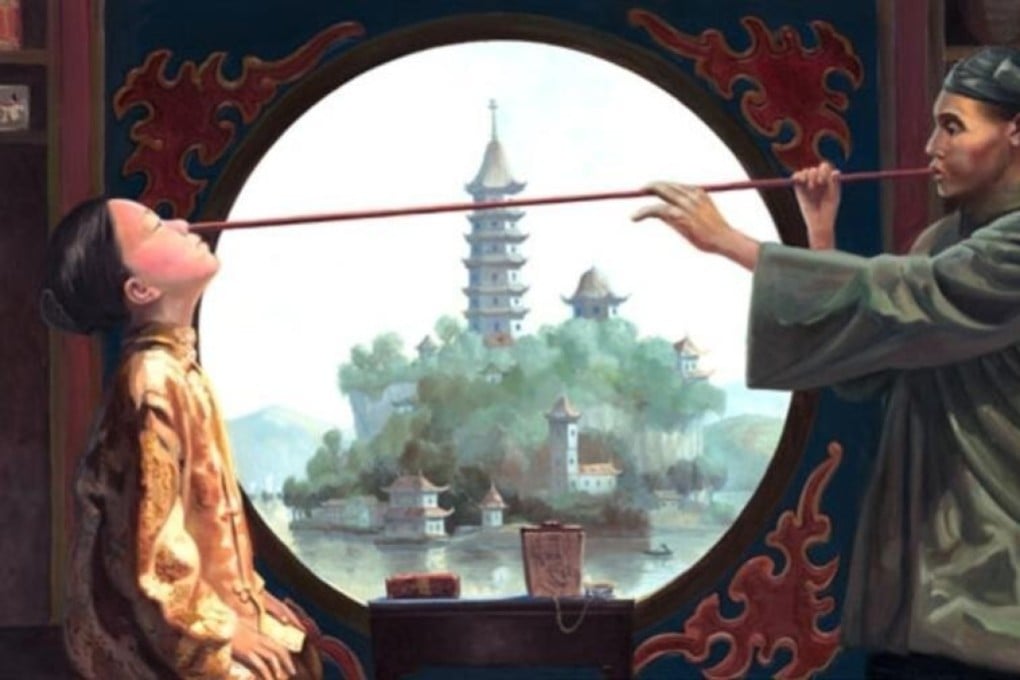

There were several ways a person could be immunised using this technique. The pus of the pox from an afflicted person would be collected in cotton wool and stuffed up the nose of the person being inoculated. Marginally less revolting was to grind dried pox scabs to powder and blow it up the nose through a long pipe. The least repulsive method wasto wear the clothes of the smallpox “donor”. Whichever method was used, soon afterwards, the “receiver” would develop a mild case of smallpox, and two to four weeks later, would recover and gain immunity.