Language Matters | How the word ‘education’ came to have two distinct meanings

- Passing along knowledge is one thing, bringing out an individual’s character is quite another

- Chinese exam boards expunging controversial topics raises more questions than it answers

So what does education encompass?

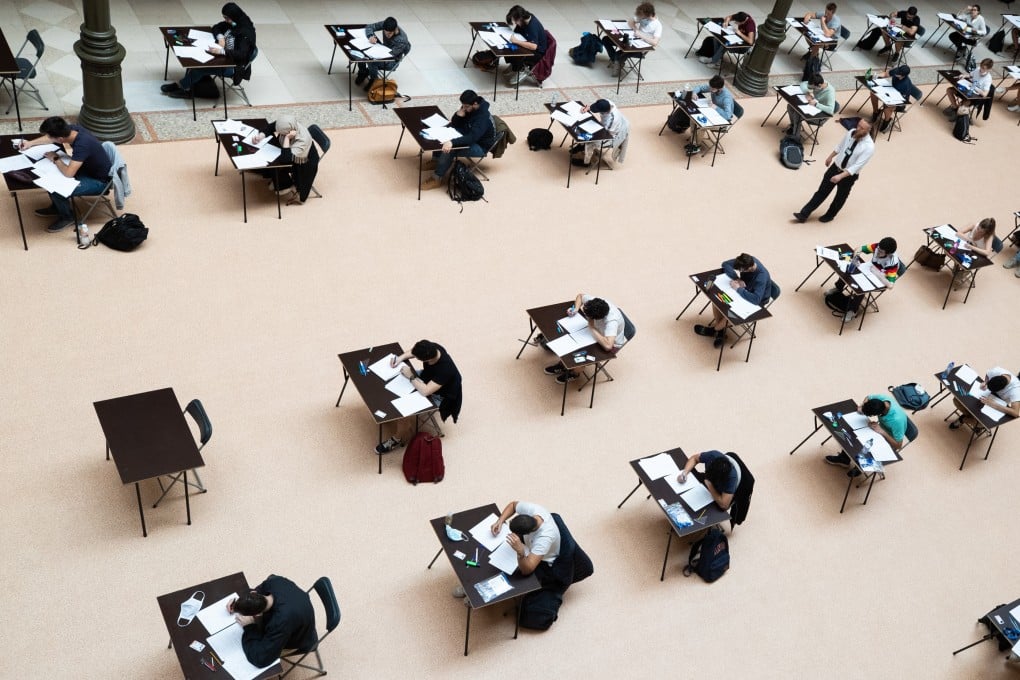

A primary, well-recognised definition of education involves the systematic instruction, teaching or training in various academic and non-academic subjects received by a child or an adult, typically at school or university. More fundamentally, education is also the process of bringing up and nurturing a child, with reference to forming character, and shaping manners and behaviour.

The word entered English, first in the late 1520s and more regularly from the 1600s, from the Middle French education and classical Latin e ducatio n - and educatio , which are based on educat- , the past participial stem of educare. Educare does indeed hold the meanings of “to rear, to train”.

Another related, though distinct, sense of education involves the culture or development of personal knowledge or understanding, growth of character, and moral and social qualities, as contrasted with the imparting of knowledge or skill. This meaning is believed to have developed most likely through influence of the other classical Latin word related to education, educere.

From the Latin ex- (“out”) + ducere (“to lead”), which comes from the Proto-Indo-European root *deuk- (“to lead”), educere means to bring out, lead forth, draw out (as well as further meanings in medicine and chemistry involving drawing off medicaments or isolating a substance from a compound or mixture) – thus underscoring the connotations of a person’s intrinsic qualities being drawn out.