Then & Now | Why passports, BN(O) and otherwise, mean so much more than nationality

- Speculation abounds regarding the future status of Hong Kong Chinese BN(O) passport holders

- A Post Magazine columnist reflects on his own experience with the ‘second-class’ document

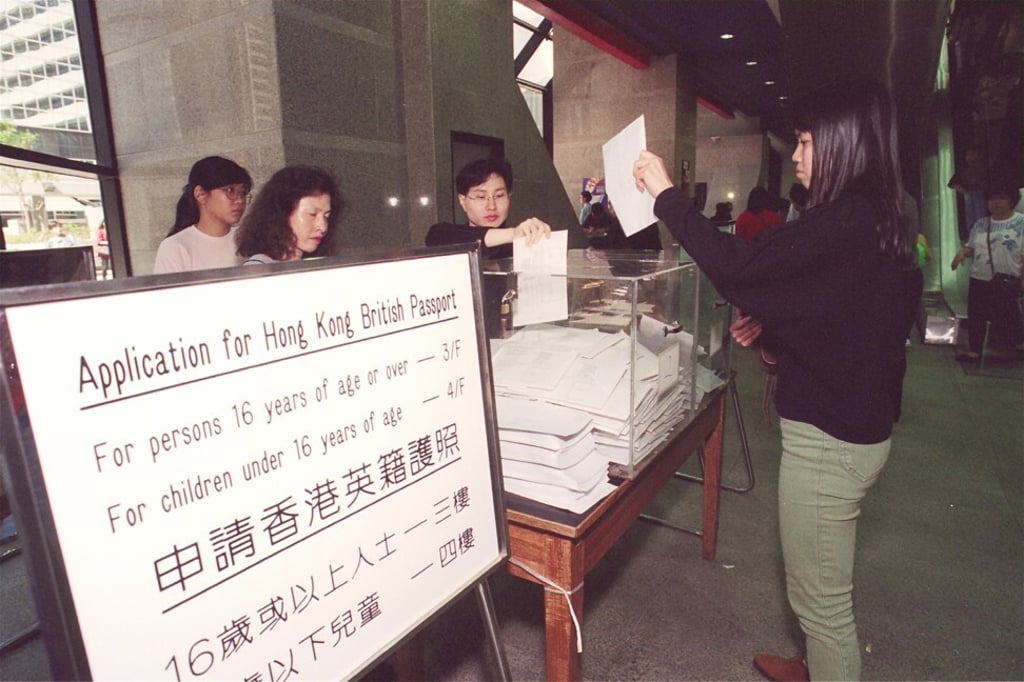

Little remembered today, it was possible to apply to become a British Dependent Territories Citizen before the handover; this seemed like the right thing to do – it signified commitment. My chosen identity in Hong Kong has always been that of an immigrant – never a transient – and all life’s selections led to that final decision to make the city my permanent home.

So one baking hot summer’s day in 1996, I queued outside the Immigration Department to register, and was eventually issued with a certificate of naturalisation, some seven months before the British Dependent Territory – Hong Kong – officially ceased to exist.

When interviewed, I was asked by the bemused official if I was doing this to claim public assistance or to register for public housing. No, I was not. Consular inquiries indicated that my Australian passport could not be returned; BN(O) status conferred “nationality” but not citizenship – voluntary statelessness was not an option.

Nevertheless, I duly applied for a BN(O) passport, and travelled the world on it. This experience was invaluable – it opened my eyes to the not-so-subtle discrimination holders of “second-class” citizenships endure.