Then & Now | Busting the myth of Portugal’s ‘benign’ colonial influence in Asia

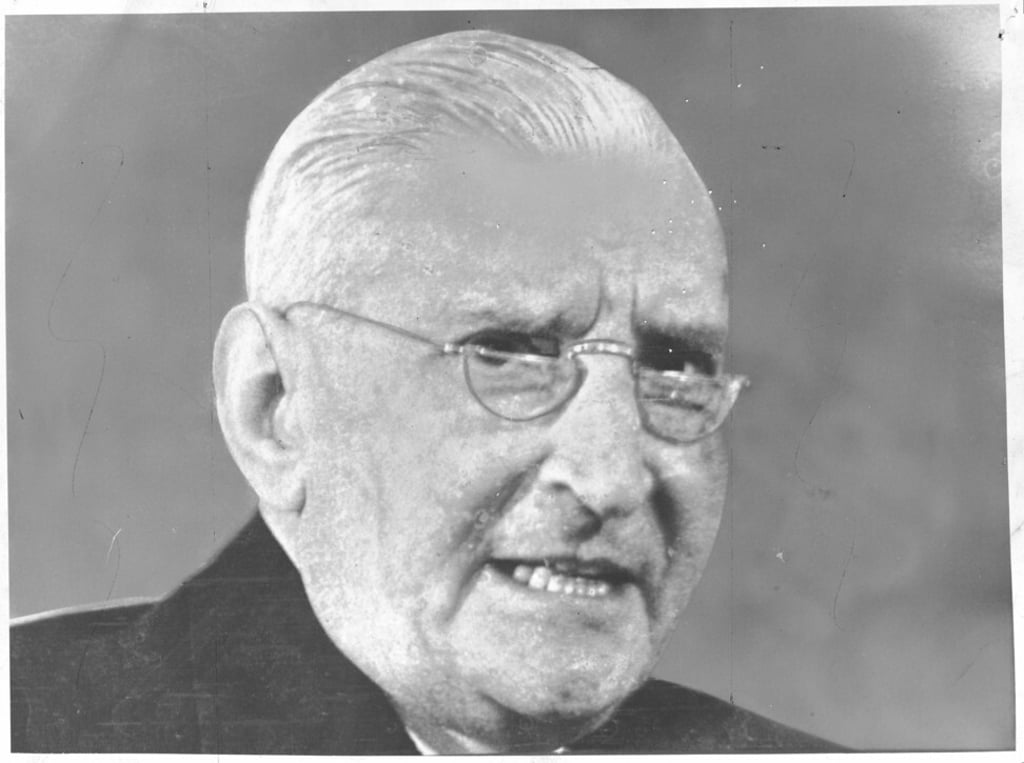

- Portuguese dictator Antonio Salazar propagated the idea that Portugal was a ‘different’ colonial power with amiable relations with local populations

- He cited the extent of interracial marriage and cultural intermingling as evidence for this, but the truth is rather different.

History largely consists of the intersections between fact- and evidence-based truth, and myths, legends, fables and tall tales, convenient or illustrative, which conceal as much as they reveal. Throughout human history, all societies have had their own foundational myths, heroes and villains that solidify into time-honoured “fact.”

People believe a myth’s essential truth (or otherwise) because they want to believe it; nuance, for many, remains a profoundly uncomfortable space. The centuries-long history of the Portuguese in Asia offers an illustrative, multilayered example.

A long-prevalent myth, perpetuated during Portugal’s fascist Salazar regime (1932-68), was that the country’s legacy of overseas expansion was profoundly different from other European colonial experiences. Evidence for this, allegedly, was the extent of racial intermarriage and cultural intermingling, creating new and distinctly different peoples, cuisines, languages and modes of living, from Brazil to tropical Africa to maritime Asia.

Picturesque hilltop forts bristling with antique cannons, gently mouldering tropical Baroque churches and the like, lend a beguiling atmosphere to its former colonies in Goa, Malacca and Macau.

But was the 16th century Portuguese presence and its later legacy really as benign as it was fondly recalled by a right-wing dictatorthree centuries later? Abundant historical evidence indicates their conquistador ferocity.