Then & Now | How handwritten notes help bring the dead back to life

- Marginalia in books, on cover sheets and on scraps of paper add telling personal details and the private thoughts of individuals

- Sorting the papers belonging to a late Portuguese friend led this columnist on a journey of discovery

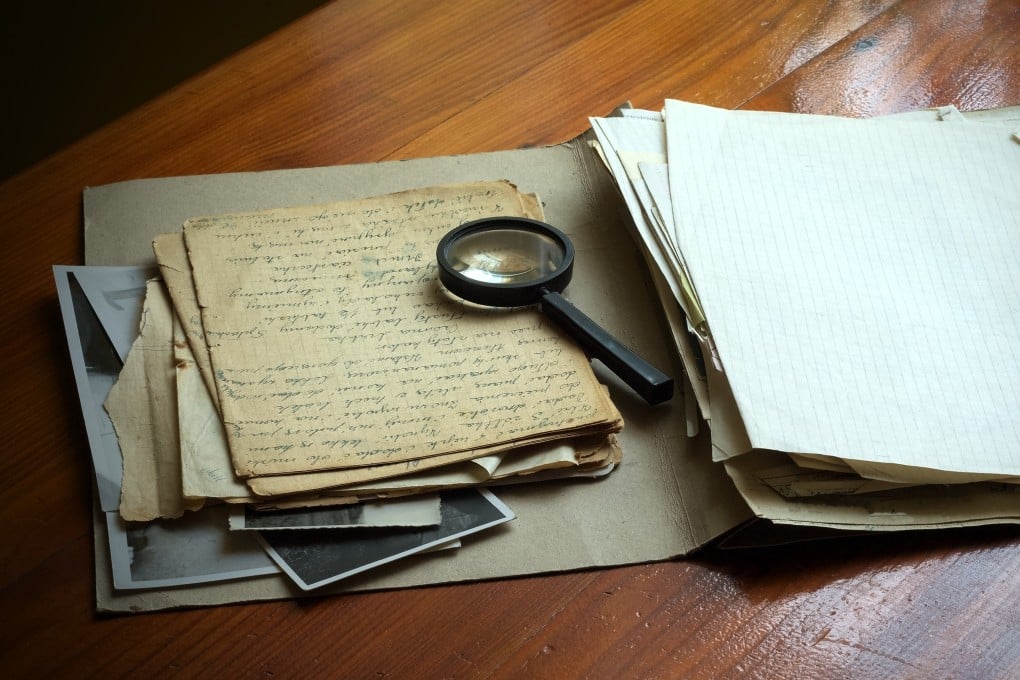

Among the unexpected joys of historical research are the occasional glimpses archival documents offer into the minds of long-ago personalities. These are most candidly revealed in marginalia – notes jotted down in the margins, or pinned to the relevant sheet on an extra piece of paper.

Books with scribbles and margin marks may be a bibliophile’s nightmare, but they reveal the private thoughts of previous owners. For biographers working with limited material, these scrawlings can provide invaluable insights.

Aged official files, bundled together with “India tags”, lengths of cord with metal crosspieces at either end, which could be threaded through a punched hole to keep related pieces of paper together, are another likely source. Covering pages illustrate the viewpoints of different officials as a file made its way up and down corridors, via various in and out trays.

Interdepartmental warfare, venomous personality clashes, small-pond rivalries and long-simmering bureaucratic spats inevitably leave their flyspecks behind for later eyes to reconstruct. Past events, long-dead actors and forgotten tensions are brought vividly back to life in this way.

History, after all, doesn’t happen in a vacuum; human beings, with their manifold strengths and failings, are integral to the process.