Chinese education through history, from the ‘Six Arts’ to Confucianism, repressive rote learning and Western-style modern schools

- China had one of the most developed education systems in the world before the modern era, including ‘international schools’ that drew students from far and wide

- But the rise of neo-Confucianism and the ‘eight-legged essay’ eventually forced much needed reforms, with Western-style modern schools introduced

Not having any children means that I am spared the worry over their education, a bane that afflicts almost every parent I know – from the quality of schools and their proximity to their homes, to fretting over little Wing Sze’s grades or Wai Keung’s future prospects.

Before the modern era, China had one of the most developed education systems in the world. The very first schools in ancient China were established by the state to educate sons of the high-born. Students at both elementary and secondary levels were taught the Six Arts, which were the major arts of ritual, music, archery and carriage driving, and the minor arts of literacy and arithmetic.

By the Western Zhou dynasty (c.1046BC-771BC), places in these state schools were given to exceptionally gifted commoners from across the country, but few were admitted. Paradoxically, during the chaotic Eastern Zhou dynasty (770BC-256BC), when the Chinese nation was divided into as many states as there were feudal lords, education blossomed.

Multiple schools of thought contended with one another – Confucianism, Daoism, Legalism and Moism, to name a few – but more importantly, there was a proliferation of private schools open to all that based their pedagogies on these philosophical systems. Education was no longer the preserve of the upper classes.

Compared with China’s royal couples, Prince Philip and Queen Elizabeth set a rare example

In the early imperial period of the Qin and Han dynasties (221BC-AD220), male children of all commoners could enrol in state schools, which were set up all over the empire at county and even village levels. The purpose of these schools, apart from providing the population with basic education, was to nurture talent for government. Graduates of the Taixue, or university, in the capital would be recruited into the imperial bureaucracy.

After Emperor Wu of the Western Han dynasty endorsed Confucianism as the sole national ideology in 134BC, China’s school curricula would focus heavily on the Confucian canon of classical texts until the early 20th century.

The imperial examination system was formally established in 606 during the Sui dynasty, and built upon in the subsequent Tang. Under this system, students of all classes, from state or private schools, could take a series of examinations and if they passed at the highest level, would be given an official position.

The excellence of Chinese education from the Tang dynasty onwards meant that schools in the capital became “international schools” of sorts. Unlike in modern-day Hong Kong and other places, where locals pay eye-watering fees to enrol in foreigner-run international schools because local schools are perceived to be inferior, the schools in Changan, Kaifeng and other subsequent imperial capitals attracted students from Japan, Korea, the Ryukyu Islands, Vietnam, Central Asia and beyond.

Advancements made in printing technology during the Song dynasty (960-1279) resulted in even greater expansion of education for the masses, but the rise of neo-Confucianism during this period cemented the rigid interpretation of the ancient philosophy as the sole path to one’s educational, and hence career, advancement. By the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the baguwen (“eight-legged essay”) became the only right way to answer examination questions, which contributed much to the stultifying quality of Chinese education – marked by the rote learning that we are familiar with – for the rest of the imperial period.

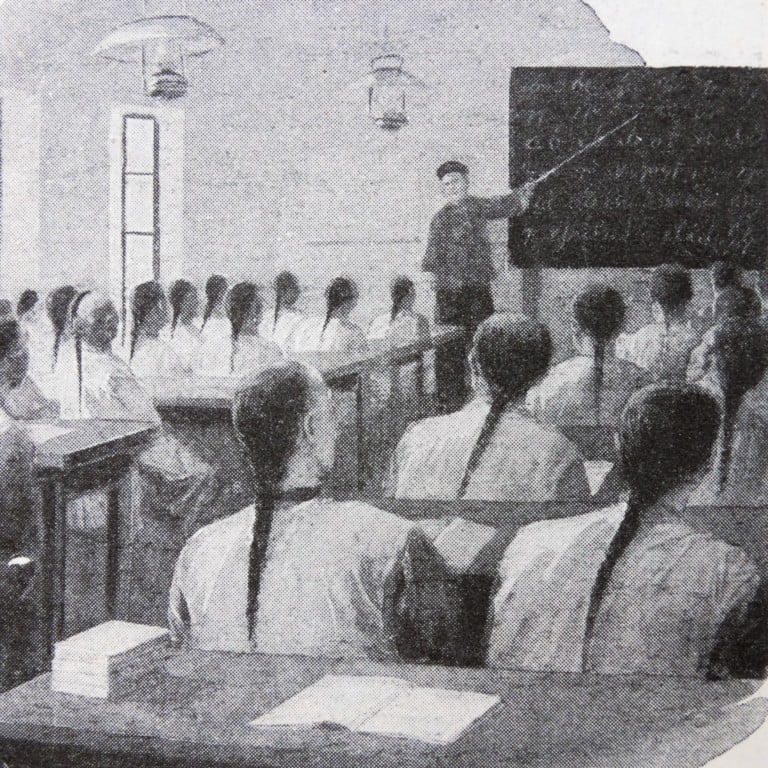

Battered on all sides by foreign powers from the late 19th century onwards, China realised that its education system needed reforms. On September 2, 1905, the Qing dynasty finally abolished the millennium-old imperial examination system. Western-style modern schools were introduced into the country and they have remained the norm to the present day.