Reflections | Men have always paid for female companionship, as Singapore was reminded by KTV coronavirus cluster

- Karaoke customers earned disdain for a cluster of virus cases in Singapore recently, but men who can afford it have always paid for women’s companionship

- Sex was not necessarily involved – courtesans were prized for their singing, dancing and playing of musical instruments, and poets and artists paid them homage

People in Singapore had been eagerly anticipating a relaxation of Covid-19 restrictions when the city was visited last month by a major cluster of new coronavirus infections involving KTV hostesses, and the men they hosted.

While I never understood its allure, nor the motivation of the men and women who seek it, paid companionship at entertainment establishments used not to be as predictably sordid as it is now. Before the world was corseted by a new puritanism in the 20th century, courtesans and professional mistresses were an acceptable, albeit shadowy, part of elite society, whose existence straddled the respectable and risqué in what the French call le demi-monde (“the half world”) and the Japanese ukiyo (“the floating world”).

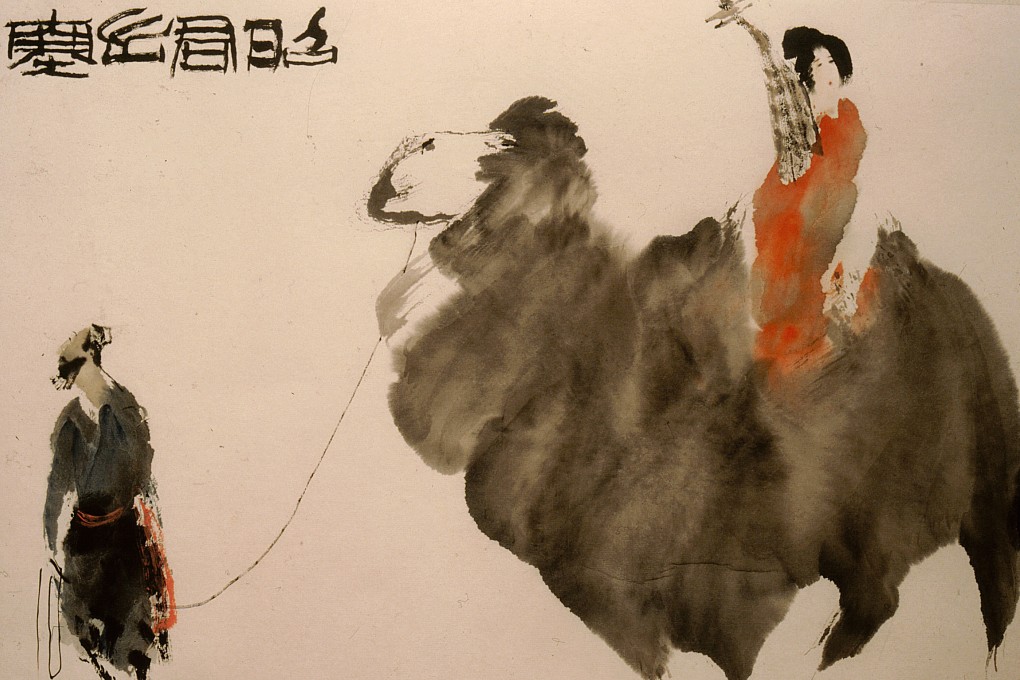

Compared to the wokeful and judgmental present, there was less shame attached to paid female companionship among the Chinese elite in the past. Men with means openly frequented the entertainment quarters in the cities. The seriously wealthy maintained a bevy of female singers or dancers in their households.

Sex was not necessarily part of the arrangement. Apart from their looks, the more sought-after courtesans were sufficiently learned to engage in highbrow conversations and witty repartee with their erudite clients. An artistic ability such as singing or playing a musical instrument was the minimum job requirement at the more exclusive establishments.

Courtesans were one of the major drivers in the creation and proliferation of the literary form known as ci poetry. Originally, ci poems were written as lyrics set to well-known tunes, and were not meant to be recited but sung, which was where courtesans and singing girls came in. Some poets in the Song period (960-1279) wrote ci for their favourite courtesans to perform, and the women thus favoured brandished these literary tributes as badges of honour, and the license to charge premium fees.