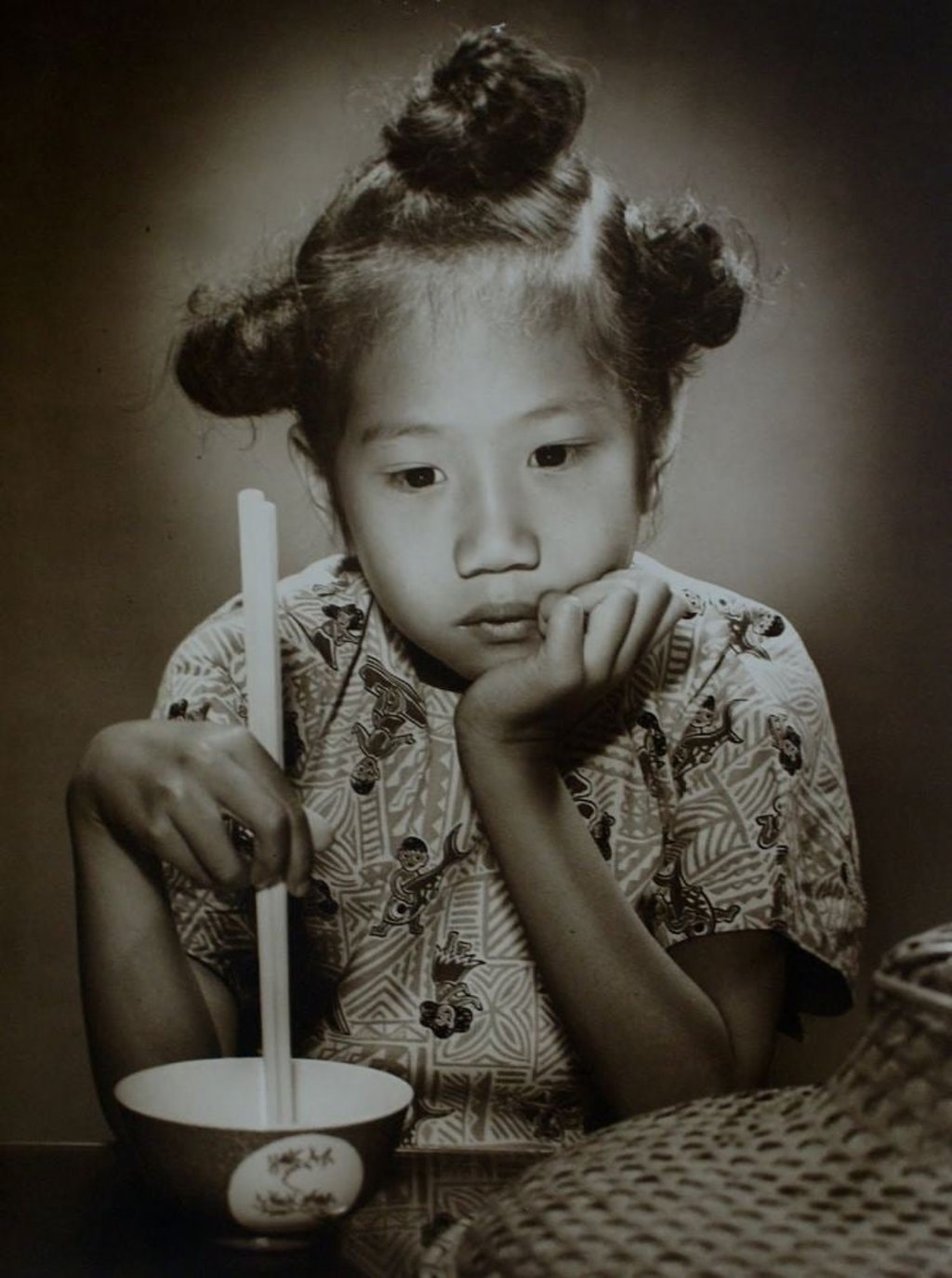

Then & Now | How Chinese-American photographer’s evocative Hong Kong images celebrate its past and a portrait by him served as quite the status marker

- Beautifully arranged, artistically lit black-and-white portraiture was a Francis Wu speciality, and he used light on smoke, mist and other ethereal reflective effects

- Wu’s studio, located in Gloucester Arcade, in Central, remained a popular landmark for decades after its opening in 1931

Old Hong Kong Government Annual Reports yield more than long-dead official statistics; these volumes provide tantalising glimpses of creative workers whose various endeavours are often unjustly forgotten. One such individual was Chinese-American photographer Francis Wu, who, with his wife, Daisy, was among Hong Kong’s more prolific photographers from the 1930s to the 70s.

Many of Wu’s evocative Hong Kong photographs make an appearance in these reports, and they form the signature plates in numerous period travel books and memoirs.

Beautifully arranged, artistically lit black-and-white portraiture was a Wu speciality. In those years, for most people, a professionally posed personal photograph was only taken at significant life events, such as weddings, graduations or a major birthday or anniversary. Those leaving Hong Kong more-or-less permanently, whether for overseas study or emigration, would get a series of portraits taken as mementoes for friends and family left behind.

Given the overall costs and difficulties of return travel, some “significant others” would probably never be seen again; a high-quality photograph created a permanent, poignant reminder of faraway people and places, and earlier shared lives.

After the Communist takeover in 1949, numerous émigré photographers from China decamped to Hong Kong. Shanghai photographers, in particular, were known for highly sophisticated special effects. Photographic equipment – unlike other professional accoutrements – was highly portable; the contents of a small suitcase could be enough to help an otherwise penniless refugee make a fresh start, along with technical skills acquired elsewhere.

Well into the 1960s, private photography in Hong Kong was largely the preserve of the wealthy. Film stock, processing and printing were expensive, relative to most wages. Cameras, lenses, flashes, reflectors and other sophisticated gadgets were beyond the budget of most people. Even when prices started to fall – Kodak’s Brownie box camera, and various imitations, revolutionised photography all over the world in the interwar years – complicated equipment was still too expensive for most purses.