How Christmas in Hong Kong evolved from a European affair to a Chinese religious festival, until an American Santa Claus swept all before him

- Early Chinese Christian congregations in Hong Kong observed Christmas as a religious obligation – there was little feasting or gift-giving going on

- From the 1920s, the idea of a secular Christmas motivated by consumer spending began to appear in Chinese port cities. Now it’s a seasonal party open to anyone

How has Hong Kong celebrated the Christian festival of Christmas since early times, and in what ways did this change as society expanded, diversified and evolved?

Early European communities here celebrated Christmas according to their own national traditions – British, French and German variants abounded.

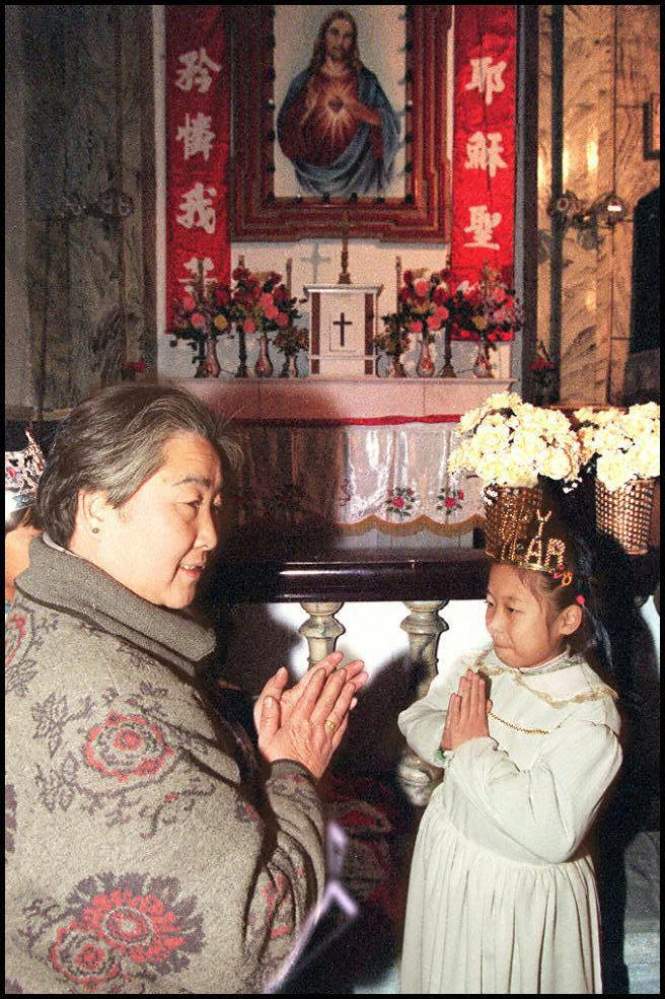

As time went on, emergent Chinese Christian congregations in Hong Kong observed their new festival, but they did so entirely as a religious obligation. Feasting, gift-giving and other aspects borrowed from European traditions were mostly absent.

Gradually, these elements became part of Chinese Christian Christmas customs, which varied according to the beliefs of specific denominations.

Churches were appropriately decorated for the festival, and as soon as it was finished, reusable items were stowed away for another year. These days, municipal and corporate Christmas decorations often serve double duty until Lunar New Year, with minor pre-planned variations.

A major Christmas player in Hong Kong was the Portuguese community. By the 1930s, this group formed the second-largest permanently domiciled community in the colony (behind combined groups of ethnic Chinese, and significantly ahead of the British population).

Local Portuguese Christmas customs – as one would expect from a sizeable community descended from centuries of cultural creolisation in Macau and elsewhere – were a beguiling mélange of Roman Catholic religious practices and regionally specialised recipes that originated everywhere from Lisbon to Nagasaki, via Africa, Goa, Malacca, Timor and Macau.

In a home-based society communally centred on churches, traditional recipes and habits of generous hospitality were matters of pride; production and distribution of high-quality festival foods – especially at Christmas – were taken seriously.

Nativity connections were commonplace: traditional biscuits, known as fartes, were shaped to represent the pillow of the infant Jesus; Bolo Menino – “Little Boy Cake” – was a light, spongelike confection that had similar connotations.

Protein-heavy foods were served during Christmas dinner; the beloved Diabo – literally, “The Devil” – was a thrifty way to transform leftover roast meats into a hearty Boxing Day casserole, and every family had their own variant. Often livened up with curry powder, dried chillies and other high-powered seasonings, its pungent flavourings also helped disguise less-than-fresh ingredients.

From the 1920s, as the worldwide craze for all things American washed across the Pacific to the China coast, the then-curious, now-universal concept of a secular Christmas motivated by consumer spending began to appear in Hong Kong, Shanghai and other internationally influenced Chinese port cities.

In this new form, heavily decorated, snow-covered Christmas trees and a jovial, red-suited Father Christmas took centre stage, and songs such as Jingle Bells, Rudolf the Red-Nosed Reindeer and White Christmas replaced religious carols. With these modifications, a hitherto Christian festival was democratised into a seasonal party, open to anyone who wished to take part. Over time, this has become the standard Hong Kong-style Christmas celebration.