Face masks’ wide public use began with Spanish flu, and soon embroidered ones became popular

- There’s nothing new about wearing face masks to combat the spread of disease – reusable, patterned cloth ones were worn by many in the Spanish flu epidemic

- The practice spread widely, even to rural Australia, as this writer was reminded on a visit to an elderly godmother soon after the Sars outbreak ended in 2003

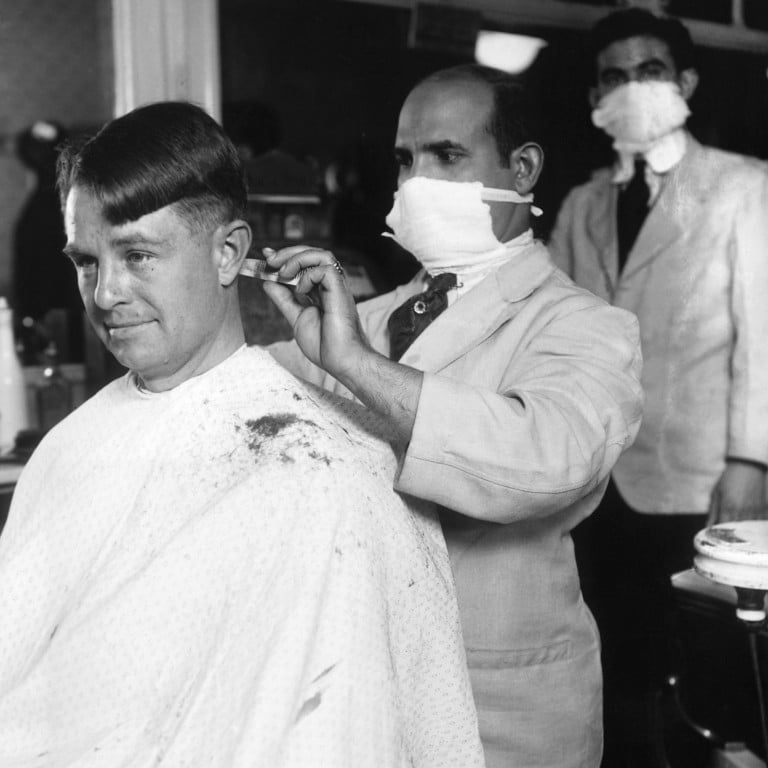

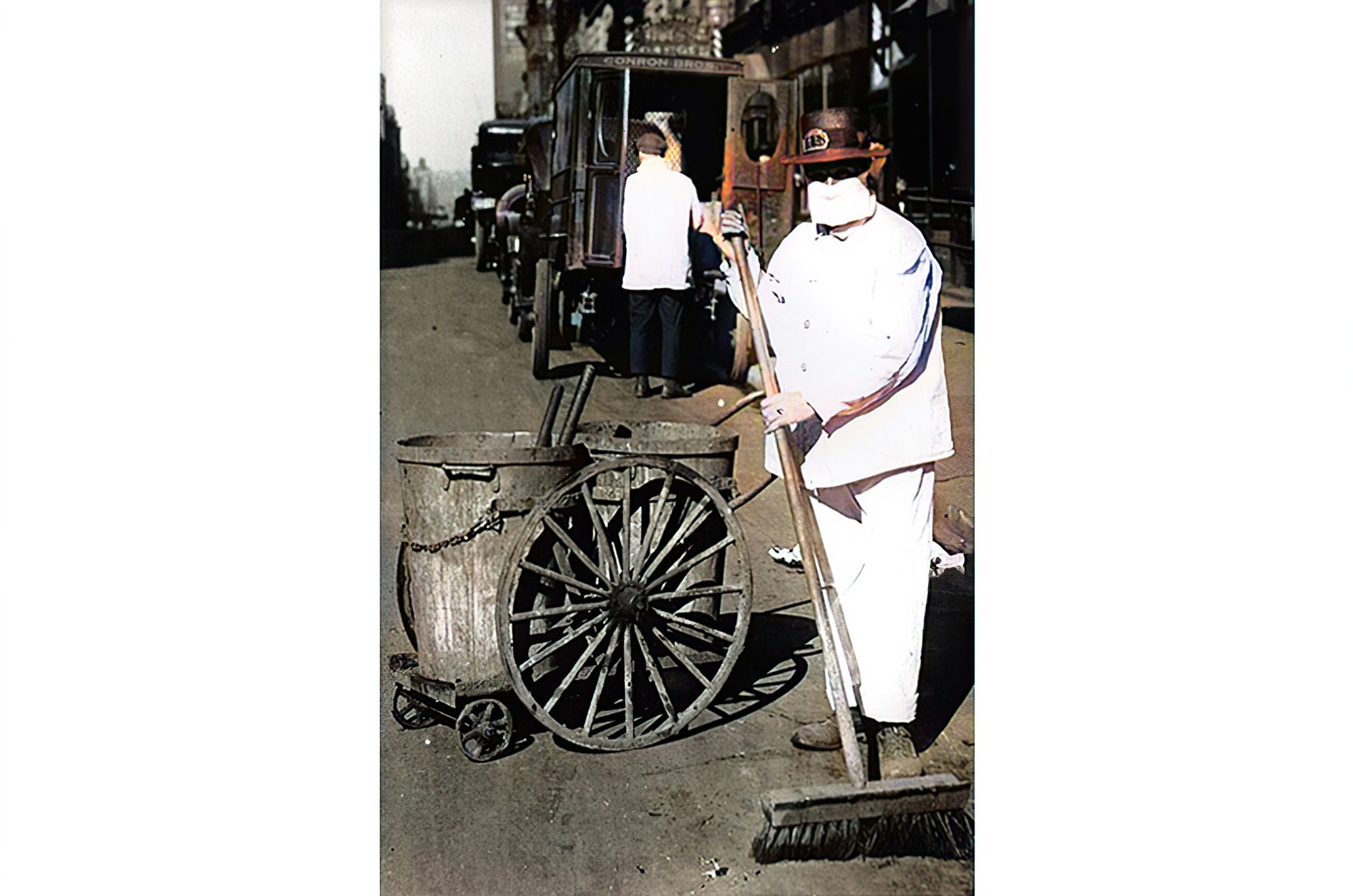

The Spanish flu epidemic, which broke out in 1918 and claimed tens of millions of lives by the time it finally subsided, in 1921, first brought the concept of face masks to the world’s attention.

Hitherto seen only in operating theatres and similar medical settings, this earlier global pandemic helped make populations aware that forms of nose and mouth covering, such as face masks, helped reduce the spread of highly transmissible infectious diseases.

Confirmed cases were isolated, and camp-produced masks, made from white cotton, gauze or other fabrics, were worn by all those undergoing quarantine, and anyone else who came into close contact with them. These masks were sterilised by boiling before reuse. Scarce resources meant single-use disposability – the norm today for such items – was impossible.

Somewhere, she had read that certain local fashion designers – whether to be trendy or ironic had never seemed clear – had used beaded face-mask designs as part of their season fashion collections; this particular nonsense naturally attracted much practical, countrywoman’s mirth. “Now, how on Earth would something like THAT ever hope to keep the germs away?” she chortled.

Reusable cloth face masks had been a dimly remembered part of my godmother’s infancy and early childhood – she had been born in 1919, the year the Spanish flu really began to spread around the globe.

On recalling that she still had them, we pulled out the battered fibre suitcase from under the bed in the spare room, in which Jimmy, her much-loved, threadbare, jointed teddy bear, Margaret the celluloid sleeping doll, whose porcelain eyes opened and shut, school prize books, old birthday cards, and all the other carefully preserved treasures and souvenirs from her long-ago bush childhood, were carefully stored.

Tucked away in a brown paper envelope, among other handmade garments, were several baby- and infant-sized cloth face masks, brightly embroidered with bunny rabbits, sprays of flowers, Red Cross symbols and other patterns, along with a few adult-sized versions that her mother had made to match.

Like the current Covid-19 pandemic, the Spanish flu took a few years to finally burn itself out globally; meanwhile, these items were everyday attire in rural Queensland and – much like today’s commercially available patterned masks – some people took the opportunity to stamp an individual style on what was, ultimately, a tiresome, health-driven necessity.

To my lasting regret, I didn’t think to photograph these historically important artefacts, and sadly have no idea what eventually became of them when that dear person finally passed away, several years later.