Reflections | How Chinese place names like Beijing, Xian, Guangzhou changed under foreign control, and how the new monikers came about

- While China was never fully colonised in its modern history, parts of it came under the control of foreign powers from the late 19th to the early 20th centuries

- ‘Postal romanisation’ names such as Peking, Amoy and Canton were abolished and replaced by Mandarin-based pinyin names in 1964

In addition to Kuala Lumpur, the state of Penang is the other place in Malaysia that Hongkongers are familiar with, especially the state capital, George Town. But for some time now, there have been calls, led by a Malaysian academic, to change the name of George Town to its former name, Tanjong Penaga.

Since Malaysia’s independence from Britain in 1957, many place names have been changed. In Kuala Lumpur, major thoroughfares saw name changes, like Mountbatten Road to Jalan Tun Perak. In the rest of the country, towns like Teluk Anson became Teluk Intan, and Province Wellesley, the mainland portion of the state of Penang, was renamed Seberang Perai.

George Town, named after the British king George III, is among the colonial-era place names in Malaysia that remain in use today.

Of course, Malaysia isn’t the only country to rid itself of place names imposed by their former colonial rulers. India is another famous example, though name changes in the subcontinent have mostly involved restoring the original pronunciations from the Anglicised ones, such as Bombay to Mumbai and Bangalore to Bengaluru.

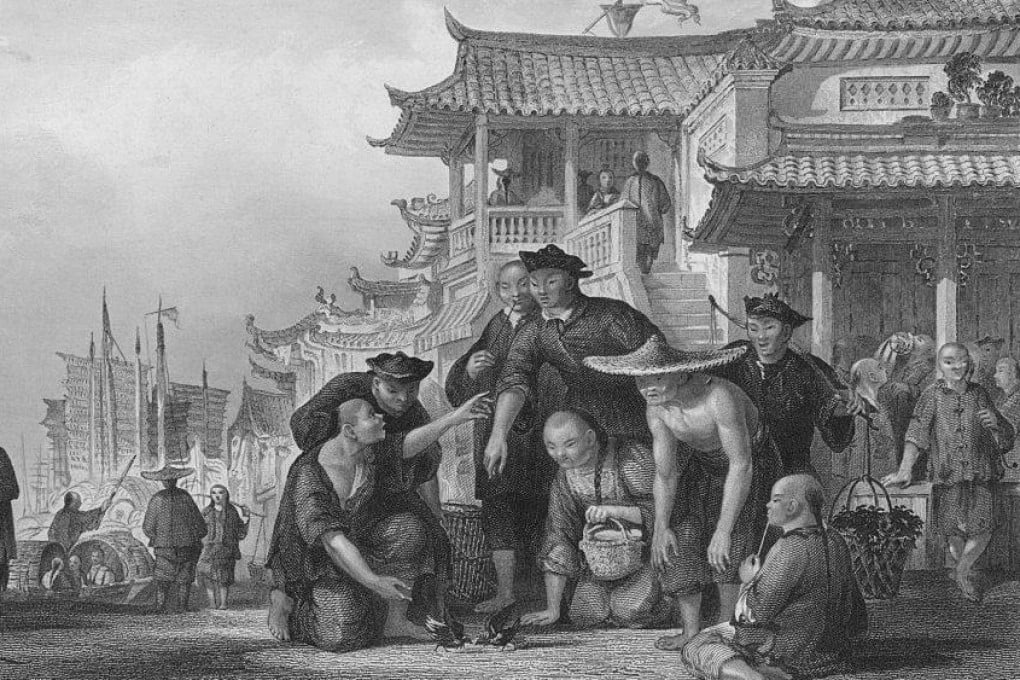

Chinese place names also underwent extensive changes in the 20th century. While the country was never fully colonised in its modern history, parts of it came under the control of foreign powers such as Britain, France, Germany, Japan and Russia from the late 19th to the early 20th centuries.

Like India, most name changes were made to their pronunciations and romanisations. Before China adopted the Hanyu Pinyin system of romanising Chinese, place names were rendered in what is known as the postal romanisation system. Beijing was Peking, Chongqing was Chungking, and so on.