Chiang Kai-shek used Western journalists to promote his Nationalist cause abroad – including a controversial Australian radio host

- Frank Clune was a prominent radio host and author in Australia who, despite supporting the White Australia policy, was transfixed by Asia

- In Taiwan, Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek wooed Western reporters in the wake of the Chinese civil war to get them onside, and Clune was one of them

“Shock jocks”, controversial radio hosts, are nothing new. Their predigested opinions and populist world views often exert an outsized political influence among regular listeners.

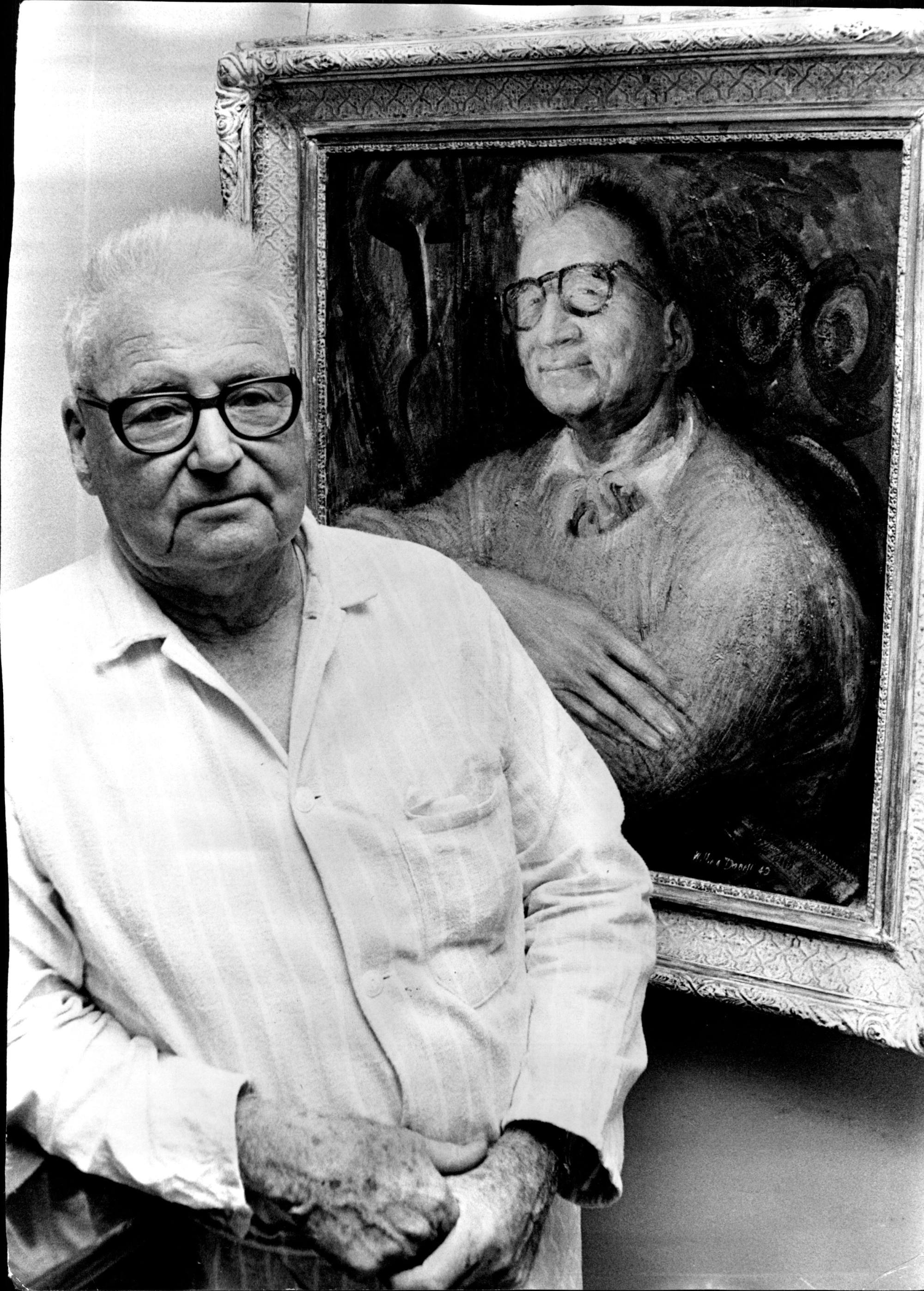

One Australian example, wildly popular in his lifetime through nationally syndicated broadcasts, though largely forgotten today, was Frank Clune (1893-1971).

Clune knew his market, and unabashedly broadcast and wrote for “Mr and Mrs Average” – a domestic audience who, decades before inexpensive mass travel, would never have visited the exotic, faraway places he vividly described.

Clune was a staunch defender of the White Australia policy that prevented immigration by non-Europeans and he periodically articulated this in terms more patronising and condescending than openly racist.

Hong Kong, at various periods, features tangentially in his works.

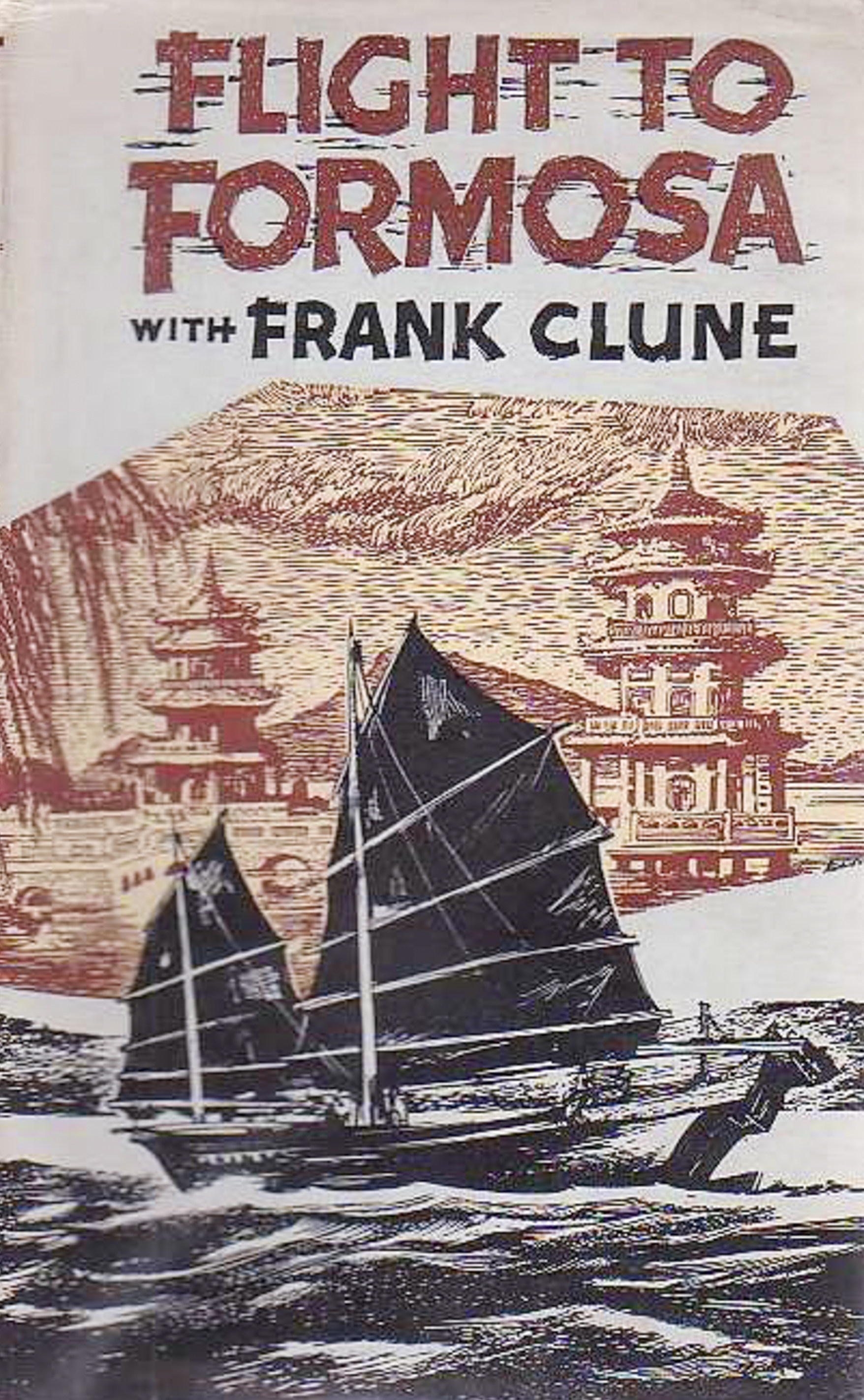

As the title suggests, Flight To Formosa (1958) covers a visit to what is now known as Taiwan, also via Hong Kong – the usual transit point in those years. Several chapters vividly contrast Hong Kong’s post-war development, population increase and overall visible changes with observations from his pre-war visit.

Closer exploration of long-ago books like these, whose titles do not outwardly suggest any local connection and are overlooked by time-pressed researchers, reveal something new and unexpected about the place. What Clune’s writing lacks in background research is amply compensated by sheer enthusiasm.

Careless of hard facts when these annoyances didn’t suit whatever rollicking narrative Clune had chosen to create, these books are essentially annotated travel diaries, whose bones clearly show through flesh padded on later.

Nevertheless, Clune’s outsider insights into people, places, everyday life and the general feeling of the times provide useful contrast to accounts written by long-term residents.

Positive coverage of places such as Taiwan – as a reciprocal expectation by their hosts for a generous, all-expenses-paid junket – were inevitably accommodated.

Lessons from history: how Chiang Kai-shek lost China

Personal access to visiting journalists was key. Productive, popular personalities such as Clune, with significant followings in their home countries, would generate goodwill dividends that far exceeded the couple of hours expended.

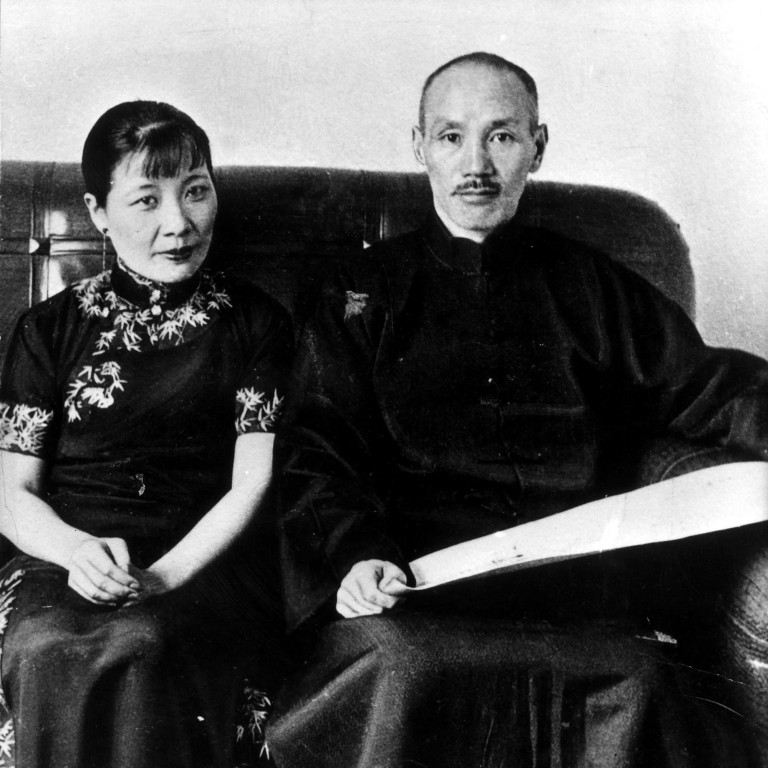

By the late 1950s, the couple’s foreign-oriented PR exercise had been pared down to a winning formula, which varied in time and intensity relative to their guest’s perceived influence.

China 1949: why did the Communists win?

An hour’s friendly chat – in reality, a tightly focused political monologue by Madamissimo, with occasional questions permitted – was invariably interrupted by an “unscheduled” walk-in from the Generalissimo, who had “unexpectedly” just heard of the important visitor’s arrival, and wanted to extend his personal regards.

As Chiang spoke no English, his American-educated wife acted as his interpreter, with her charming Southern lilt deployed to the fullest. Ten minutes maximum, and several exchanges of compliments later, Chiang went on his way, with the visitor suitably overawed, because the great man had taken time out to greet him personally.

These interviews concluded with a well-chosen “small token” from Madamissimo, a signed photograph, as well as something charmingly Chinese for his wife, with her name carefully inscribed on the attached card.

This artfully artless strategy worked every time; Flight To Formosa positively fizzes with Clune’s gushing enthusiasm for the defeated Nationalist cause and for Chiang Kai-shek and Madamissimo in particular.