As Hello Hong Kong campaign woos visitors, remember mass tourism is a recent phenomenon; in ancient China there were just 4 classes of traveller

- It’s mass tourism or bust for one Chinese city with the launch of the Hello Hong Kong promotion, yet until recently long-distance leisure travel was unknown

- The tourists of ancient China were emperors and their entourages, merchants, intellectuals – the ‘influencers’ of their day – and farmers resting from toil

“Hong Kong is ready to welcome you all again,” beckons the jaunty video promoting the city as a tourist destination. “It’s time for all of us to say ‘Hello Hong Kong’!”

The “Hello Hong Kong” campaign was launched recently to revive the city’s floundering tourism industry, which had suffered successive knocks since 2019 – first from the violent social unrest just before the pandemic, then the worldwide pandemic itself, and finally the government’s insistence on keeping Covid-related restrictions for inbound travellers long after most countries had removed theirs.

Before the advent of better means of transport, the rise in disposable income and greater safety and protection for travellers, what was “tourism” in China like? Like the rest of humanity in the pre-modern world, most Chinese did not travel long distances and very rarely for pleasure.

There were basically four groups of travellers in ancient China. The first were VIPs like emperors for whom money was no object. A few rulers, such as the First Emperor (259–210 BC) of the Qin dynasty, toured their empires to gain insight, however superficial, into the lives of their subjects.

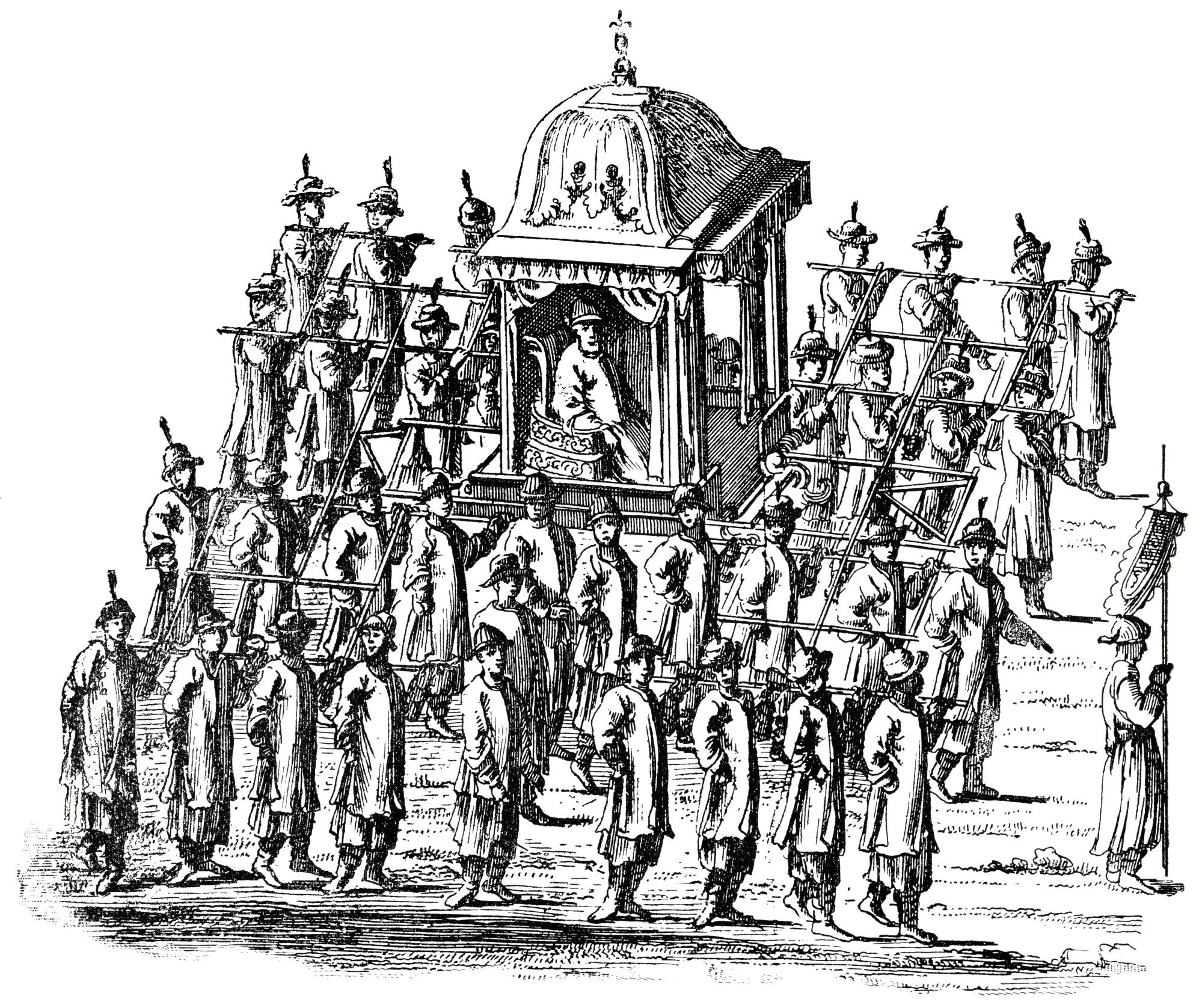

With a massive entourage and magnificent regalia accompanying the emperors, these grand imperial tours were also designed to awe the people into willing subservience.

There were, of course, rulers who travelled across their realms solely for personal pleasure, often at enormous expense, with no real benefit to the people.

Convince Hongkongers that the city is back, and the world will follow

For the second group of travellers, money was the only object. People who engaged in commerce were indispensable to society even if they were despised by the educated Confucian elite.

Besides traversing the vast Chinese empire, travelling merchants also ventured out into foreign soil, either over land or across the seas, to buy and sell a multitude of commodities and goods.

Their travels, often taken at great personal risk, enriched the Chinese nation not only materially, but also culturally in the form of the foreign foods, customs and even ideas that they brought back with them.

Intellectuals were the most famous travellers in pre-modern China only because they left behind copious records of their travels in their poems, essays, personal letters and travelogues. Interestingly, their travels usually coincided with low points in their official careers, when they had ample leisure time.

Most of these well-read men of letters travelled for self-edification, preferring to visit sites of great historical or literary significance, or places of great natural beauty.

They were the “influencers” of their day, for the places they had visited and written about would become popular destinations that continue to attract tourists today.

‘Cheap and tacky’: ‘Hello Hong Kong’ tourism campaign panned by advertising experts

The last group comprised the overwhelming majority of the population – the farmers, artisans, servants and the rest of the hoi polloi. It is even debatable if they ought to be included in this discussion about travelling because they neither had the means nor the time to embark on long journeys away from their homes.

For them, “travelling” took the form of excursions, which might last one or two days, to nearby hills or lakes whenever there were breaks in their work, which were few and far between.

A comparatively recent phenomenon in human history, mass tourism mushroomed in tandem with more affluence and cheaper air travel in the decades following the second world war. Today, the effects of mass tourism are felt in many places in the world.

There is also the immeasurable carbon footprint that it generates, which affects us all.

These are not, however, the immediate concerns of many Hongkongers, especially those who are directly or indirectly involved in the tourism industry. For them, the “Hello Hong Kong” campaign simply has to work.