Ready-to-wear fashion wasn’t always cheaper than bespoke – for women in Asia, clothes tailored by travelling couturiers were once the everyday choice

- Unlike today, when ready-to-wear fashion is generally cheaper than bespoke, women in Asia in centuries past would employ travelling tailors for household dresses

- These artisans would follow contemporary trends and use different fabrics to suit customer needs, at a time when standard-fit garments were the height of fashion

For those without personal memories of what older generations wore in earlier times, surviving period clothing helps us to better understand now-transformed domestic lifestyles.

Among the first items usually disposed of when someone dies, everyday garments are soon forgotten, unless something is retained for practical reuse, or for sentimental reasons by those with space to keep them.

Outfits that a person was photographed in were usually more formal, dress-up garments, rather than what was typically worn around the house or garden in everyday settings. If someone knew that a camera was lurking, they often asked not to be photographed until they’d changed into “something better”.

Consequently, photographic evidence for everyday household wear – especially in European contexts in Asia and Africa – was unusual until the 1930s.

From Kenya and Queensland to Malaya, Borneo and Hong Kong’s New Territories – wherever home sewing was the norm – period photographs reveal a surprising similarity in basic outfits worn by European women.

Shirt-waisted, three-quarter-length one-piece frocks, belted and buttoned, formed the usual basic style. Unlike today, ready-to-wear clothes were once the expensive outfit. Handmade or home-made garments, however well cut, stylish and attractive, were seen as the lesser choice.

How airline uniforms evolved through the decades – what’s changed and why

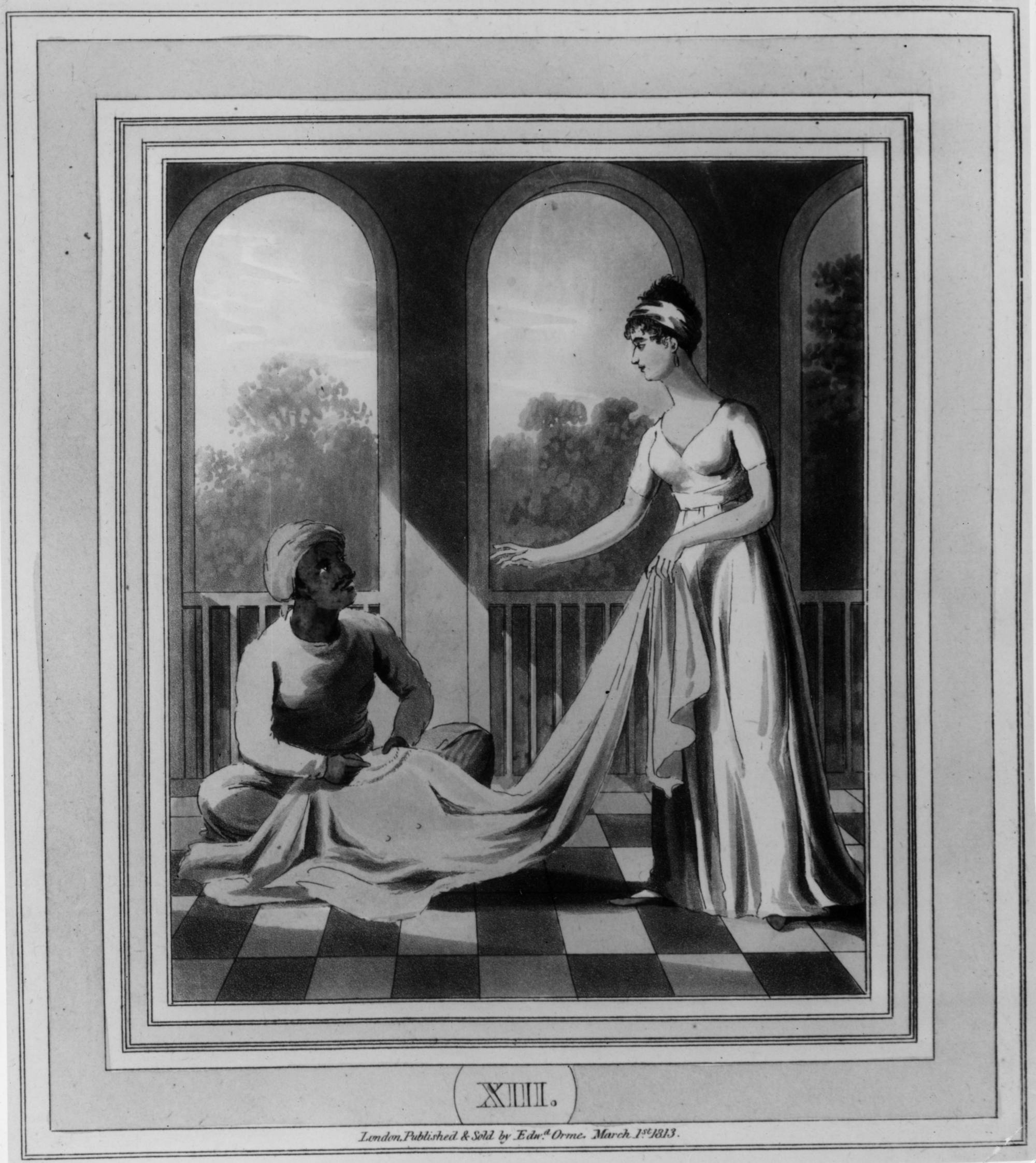

Where and by whom these garments were run up depended on the location. A visiting tailor-dressmaker was known on the Indian subcontinent as a darzi.

Engaged by a household to sew for family members and servants, he would typically be based on a back veranda where he sat cross-legged in front of his hand-operated portable sewing machine. Fittings and adjustments could be made as soon as items were ready.

In Southeast Asia, similar arrangements were made; there, these travelling artisans were known as tukang jahit.

An assortment of pattern books – usually a couple of years out of date – accompanied the jobbing dressmaker on his rounds.

From general ideas gleaned from these prototypes, after discussions among friends and family, and from working experience of previous experiments, various pick-and-mix styles evolved. Collars in one form, sleeves and cuffs in another, along with pleats and smocking somewhere else, coalesced into an often highly individual sartorial expression.

In particular, hem lengths rose and dropped and ascended once again in relative proximity to current or near-recent fashion trends elsewhere, the age of the intended wearer, how acceptable such styles would be deemed – or otherwise – in their own small community, and seasonal weather conditions.

Ancient Chinese clothing fad: cultural nod or cosplay?

Fabrics were generally selected from sample books supplied by the craftsman; particularly if heavier or more specific materials had to be ordered in, or personally chosen on periodic shopping expeditions to major regional centres with more choice, such as Hong Kong or Singapore.

Along with dress lengths, a selection of buttons, belt buckles, better-quality zip fasteners, elastics and other items were sourced and kept until a new outfit was wanted.

Key considerations were serviceability, along with long-lasting, easily laundered cloth.

In tropical conditions, where clothes soon became unpleasantly sweaty, even with minimum physical exertion, household clothes were often changed twice a day, with a fresh set worn after a midday shower.

Consequently, from Malaya and Borneo to Hong Kong and the Philippines, inexpensive cotton fabrics were preferred choices for everyday house dresses that soon faded from constant washing.

In places with distinct cool seasons, such as Hong Kong, heavier, harder-wearing silk shantung was a popular choice. Long-sleeved summer dresses could be easily teamed up with cardigans, scarves and heavy stockings to keep out winter cold.

How an American revolutionised China’s rug-making game in the 1920s and ’30s

Aprons were universal features.

Worn partly to keep frocks clean throughout the day, they also kept regularly used items handy. Anything from her wallet, coin purse and domestic keys, to scissors, secateurs, pencils and notebook – whatever the individual required during her daily rounds – could be immediately located.