Text-based art: from Mel Bochner to the ‘King of Kowloon’ to Hong Kong protesters’ Lennon Walls, what is it trying to say?

- For decades American conceptual artist Mel Bochner has been asking questions about language, communication and art with his text-based artworks

- Arguably Hong Kong graffiti artist the “King of Kowloon” did so too, and recent protesters with their Lennon Walls of Post-it notes

If one writes a text, and then superimposes further text over it, repeatedly, until the result – resembling alternately a bad case of astigmatism, misaligned typography, or a child’s scribbled out writing – conceals and confounds any possible literal reading, several fundamental questions arise.

Is it still language? Is there communication? And is it art?

American conceptual artist Mel Bochner – whose work has been shown in numerous Art Basel exhibitions, including Hong Kong – created his “Language Is Not Transparent” text-based works (the first in 1969) to provoke critical reactions about language and communication.

At face value, these images prompt reflection on the opaque nature of words. Or, as with the artist’s 2020 iteration, rendered in 15 languages (a limited-edition art cover responding to the Covid-19 pandemic), the resulting black-and-white image is meant to reflect the chaotic nature of today’s world.

At the same time, such art aims to remind us there are still truths to be found underlying the surface confusion, as well as highlight the presence of hidden agendas and ideologies of language.

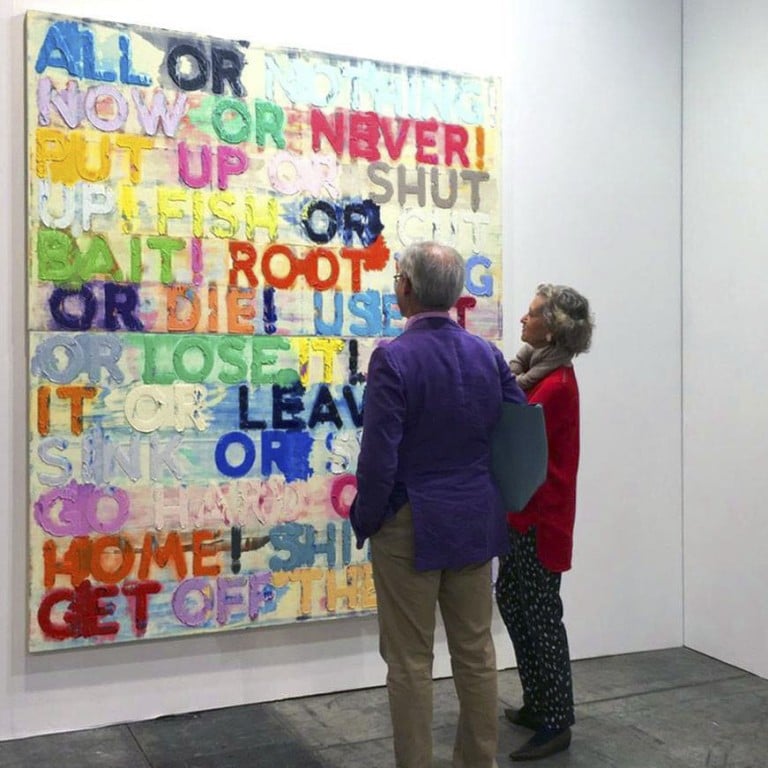

In other works by Bochner, language is conveyed in such a form that its literal meaning is subverted by the physical, visual form. This is perhaps most compelling in his 2013 water-based silk screen Silence.

The word “SILENCE!” is followed by “BE QUIET!”, “CAN IT!”, “COOL IT!”, “GAG IT!”, “ZIP IT!”, “MUZZLE IT!”, “STUFF A SOCK IN IT!”, and the work continues into the realm of the expletive.

While the goal of the literal sense of the words is the cessation of noise, their meanings are shouted in all caps, with increasingly irate force, and the hues, meanwhile, are soft and subdued. Which medium is the message then?

Bochner’s direct painting onto gallery walls – blurring the distinction between work and setting – and various explorations of ideologies, truth and silence cannot help but remind us of comparable expressions in the Hong Kong landscape.