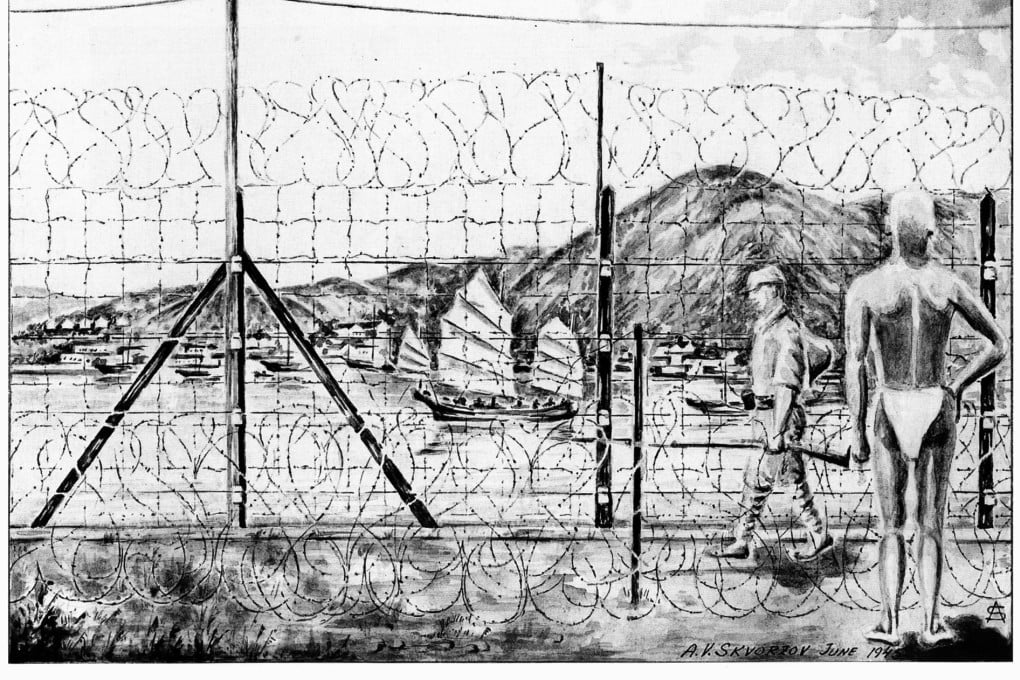

Then & Now | The Hong Kong prisoners of war for whom creating art was a diversion, and one who made it as an artist

- Given unlimited time to indulge latent artistic talent, some of those held prisoner by the Japanese took to drawing and painting portraits and scenes of camp

- Most of these men put their artistic pursuits aside in peacetime, but one ex-POW began a career as an artist, one cut short by his death at the age of 50

Visual art frequently originates and thrives in the most unlikely circumstances. During the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong (1941-45), several promising local artists began to paint, draw and sketch as prisoners of war.

Confined in overcrowded living conditions with almost non-existent personal space, some temporary escape through artwork allowed periodic respite from depressing personal circumstances.

In Hong Kong’s military POW camps, most men had little to do beyond routine daily chores. Time hung heavily, and with soul-crushing boredom ever present, activities that helped maintain morale were vital.

While this specific factor is usually overlooked, the unexpected gift of abundant spare time – essential to any creative endeavour – allowed unexpected creative energies to flourish.

Along with an astonishing array of special-interest lectures, amateur theatrical performances and musical productions, individual drawing, sketching and painting activities were also encouraged – or at least, not actively prohibited – by the Japanese.

Output varied sharply; pen-and-pencil, caricature-style drawings predominated – maintaining a sense of humour was vital in trying conditions.