The future of Komodo National Park hangs in the balance, caught between tourism industry and environmental concerns

- Rampant poaching of deer, the prey of the park’s famous reptilian residents, has caused the large lizards to shrink in size

- Local authorities push for year-long closure, but Indonesia’s central government resistant

We are barely more than a month into 2019, and already there has been talk of restricting access to more popular tourist destinations. In the spotlight this time are the 29 islands that make up Indonesia’s Komodo National Park – home to the world’s largest lizards – but, for once, pesky tourists aren’t to blame.

Speaking to English-language Indonesian news portal Tempo on January 18, the governor of East Nusa Tenggara (NTT), Viktor Bungtilu Laiskodat, said the park’s famed reptile inhabitants, “dragons” known for their hulking proportions, were becoming smaller because of a declining deer population, the result of rampant poaching.

“The NTT government will reorganise and improve the Komodo National Park so that it can further sustain Komodo habitats,” said the governor. “We plan to close the park for an entire year.”

Can Indonesia’s Komodo dragons survive Chinese tourists?

According to the World Wide Fund for Nature, Komodo dragons are extremely vulnerable to extinction due to human activity, such as the pinching of their prey, and the any closure aimed at boosting the giant lizard population would be supported by environmentalists.

Not surprisingly, though, Arief Yahya, Indonesia’s minister of tourism, is opposed to the idea.

“Closing Komodo National Park is irrelevant,” he said at the ministry’s main office in Jakarta, on January 29, as quoted by Tempo.

This followed a statement by Siti Nurbaya Bakar, the minister of environment and forestry. “Komodo National Park is a tourist destination where a lot of entrepreneurs, from the tourism ministry and others, run businesses,” she said on January 24.

Any shutdown was the concern of the central government, Bakar asserted, putting the local administration in its place, and Jakarta was collecting information to assess whether it was necessary to implement one. The Jakarta Post reported on January 30 that a meeting to discuss what Yahya describes as “the Komodo National Park polemic” would be held, although there has been no news on when or where.

NTT figures in tourism industry publication TTG Asia state that Komodo National Park received 176,830 arrivals last year, a 48 per cent increase over 2017, and as those numbers have swelled, so too has the local economy. Tempo reports that more than 4,500 people in the region, many of whom rely on tourism for their livelihood, would be affected by a closure.

However, if the plan to repopulate the park with prey doesn’t get the green light, there are fears the dragons could turn to cannibalism, and worst case scenarios see the extinction of the species. Should that happen, tourism to the remote islands would almost certainly dry up, leaving locals who work in the industry with little else to do to make ends meet.

While officials debate how to proceed, travel agencies and tour operators are left in limbo. “This announcement is too sudden,” said Abed Frans, NTT chairman of the Association of the Indonesian Tours and Travel Agencies, speaking to TTG Asia. “There were no discussions with associations, travel trade, or the community [...] 70 per cent of the community livelihood relies on the national park,” he continued. According to The Jakarta Post, Yahya was also concerned with the trouble a closure might cause travel agencies, stressing that maintaining tourism was “more important” than securing the park’s animal population.

For now, the fate of the park, and its fearsome dragons, hangs in the balance, caught between the needs of the environment and an industry that does little to protect it.

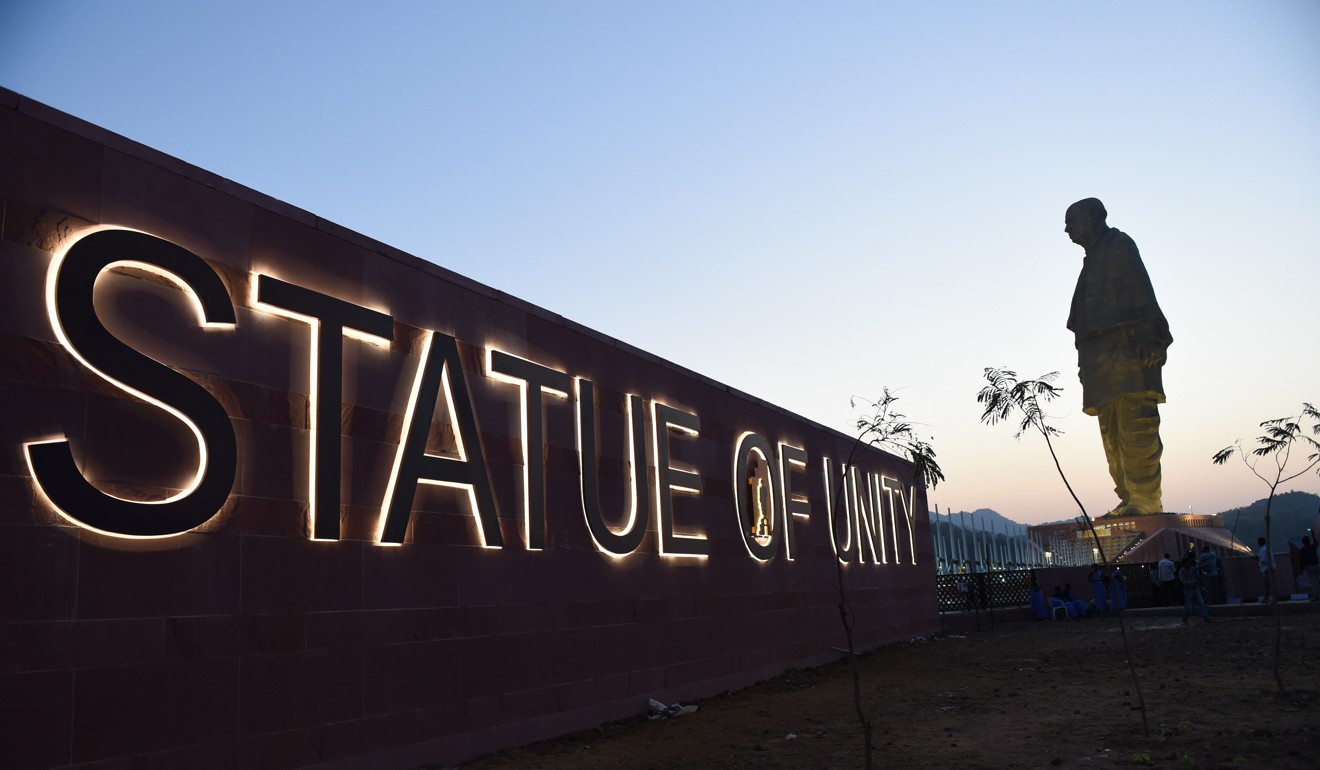

Crocodiles snapped up at India’s Statue of Unity

The Statue of Unity, in the western Indian state of Gujarat, is the loftiest in the world. Standing 182 metres tall, it was built in honour of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel (1875-1950), who played a prominent role in uniting the nation post-independence.

It is also rather remote, located as it is in Kevadiya town, in the Narmada district. The city closest to the monument, Vadodara, is almost 100km away, and Unity is about 200km from Ahmedabad, the state capital.

Most visitors make the long journey by bus. However, the government is hoping to make the statue more accessible by operating flights from four cities by seaplane, the aircraft landing in one of the lakes close by. The only problem is that the body of water is home to crocodiles, which will have to be moved.

India’s billion-dollar battle to build the world’s biggest statue

Forestry officials charged with the relocation estimate that there could be as many as 500 of the long-jawed creatures in the lake, according to The Times of India newspaper.

“We don’t know how much time it will take to make the pond free of crocodiles […] We have just been told to make the pond crocodile-free,” said K. Sasi Kumar, the deputy conservator of forests, Narmada district.

Naturally, the plan isn’t particularly popular with environmentalists, who argue that it is being executed without proper consideration or scientific analysis. “Have we collectively lost our minds?” tweeted Bittu Sahgal, editor of wildlife magazine Sanctuary Asia.

AFP reported that about 12 crocodiles have been removed from the lake to date, although there is no news on where (or even if) they have been released.

Hopefully for them, their new home will be a significant distance from any other tourist hotspots.

Pakistan is ready to receive tourists

In a bid to revive its tourist industry, Pakistan will soon offer e-visas and visas on arrival for international travellers. According to a report in the Dubai-based Khaleej Times, citizens possessing any one of 175 passports will be eligible for electronic visas, while those from 50 of those territories, “including the US and Europe”, will also be able to get a visa when they land in Pakistan.

Once a part of the hippy trail, Pakistan’s tourism industry has suffered in recent decades, largely because of safety concerns. Cricketer-turned-prime minister Imran Khan is keen to attract travellers, though, and the economic boost that they bring.