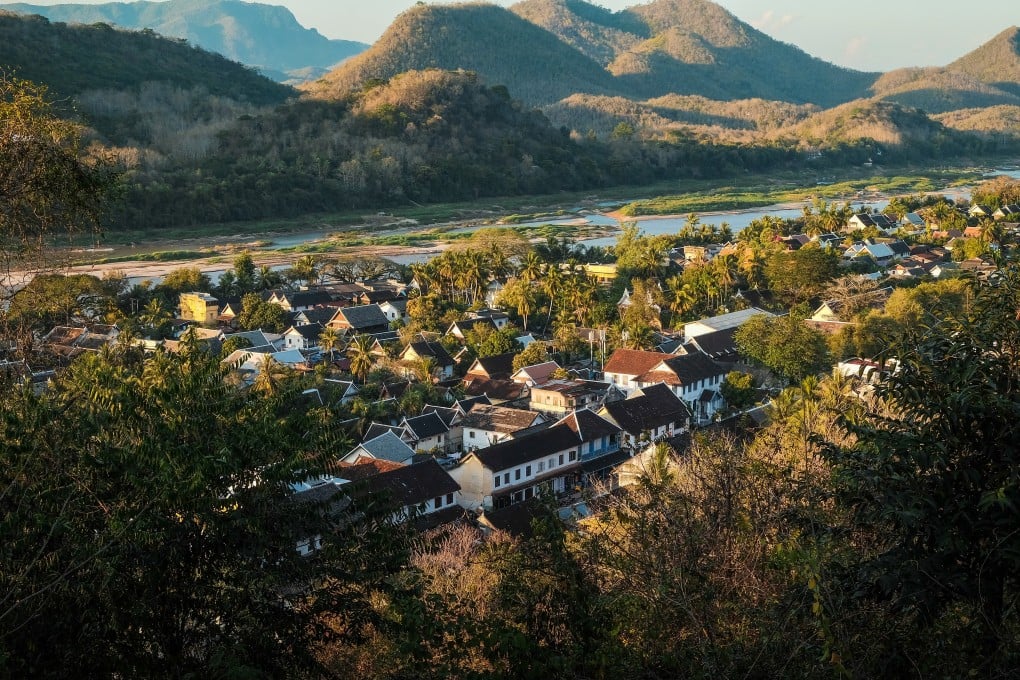

Brief Encounters | A long weekend in Luang Prabang – Laos ancient town where authentic travel experiences still exist, for now

- The daily distribution of alms to monks is evidence of the city’s commitment to tradition, but it is not the only one

- Best explored on foot, a slower pace suits the relaxed atmosphere of the architecturally gifted town

There’s a single overriding reason to fast-track Luang Prabang to the top of any travel bucket list, and that is the railway line that is currently being built between Kunming, in China, and Vientiane, Laos’ capital. It doesn’t take a venerable Laotian soothsayer to prophesy that once the trains are running right past this jewel of a Unesco heritage site – ancient kingdom and an architectural treasure house – it is going to become more than a little tarnished.

Luang Prabang’s fans list the Royal Palace Museum as the prime exemplar of times past, and the daily distribution of alms to monks at dawn as evidence of a thriving tradition. But it’s the town’s timeless, peaceful ambience that is its true intangible heritage.

The rail line is expected to open in 2021 and developers are already eyeing up the potential of sites outside the Unesco boundary. For anyone with a hankering for authentic Asian travel experiences, the next step should be fairly logical.

Where to stay

It was inevitable that the planet’s larger brand hotels should regard Luang Prabang’s attractions, visitor numbers and paucity of upscale accommodation and that their accountants would put three and three together. Rosewood, Sofitel, Aman and Belmond, to name but four, have flung wide their doors in recent years. Without exception, they’re very good. But they’re all just a bit too big for Luang Prabang, with its gentle suggestions of Lilliput.

Elsewhere in the world, entrepreneur and conservation activist Lamphoune Voravongsa might get her own television chat show, but in Luang Prabang she disdains anything so bogus as celebrity to get on with running her hotel, Satri House. Formerly the residence of Prince Souphanouvong, its clutch of 31 rooms and suites have been imaginatively restored (Hmong bed runners, Bakelite rotary dial telephones) to make it one of the most alluring boutique hotels in Asia. Regular rooms start at US$145.

Less pecunious travellers could try dropping their bags at one of a number of clean, comfortable, teak-floored guest-houses in walking distance of the main attractions, with nightly rates around an eminently reasonable US$15.

What to buy