Beyond Raffles: seven of Asia’s lesser-known colonial hotels, some gone but not forgotten

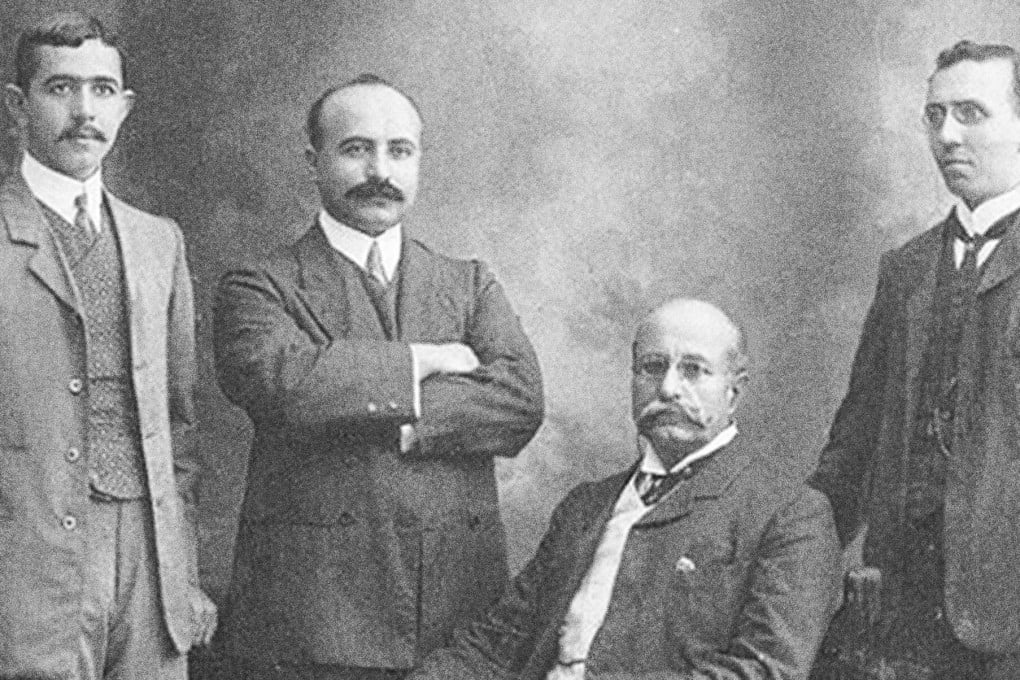

- Around the turn of the 20th century, the Sarkies brothers built an empire of heritage hotels from Singapore to Indonesia

- But the entrepreneurial siblings weren’t responsible for all of Asia’s best boutique properties, some of which still welcome guests

They figured out there was money to be made by bridging the gap between the increasing interest in travel at the turn of the 20th century and the dearth of decent accommodation. Other entrepreneurs were not slow to jump on the bandwagon, realising a healthy profit from clean sheets, taps that gushed water when they were supposed to and dining rooms free of wildlife both on and off the plate.

The Sarkies’ most successful ventures – including Raffles, in Singapore, and the Eastern & Oriental, in Penang, Malaysia – continue to thrive, dollied up and corporate logo’d but still balanced neatly atop the five-star pyramid. Others have languished or disappeared altogether, victims of changing appetites or shifting bottom lines.

And while the likes of The Strand, in Yangon, Myanmar, and Amangalla – formerly the New Oriental Hotel – in Galle, Sri Lanka, can proudly assert their cock-of-the-heritage-walk status, their lesser-known cousins also have a tale to tell.