Destinations known | Is national security law exactly what Hong Kong’s tourism industry needs?

- Protests and the coronavirus pandemic have caused visitor numbers to slump, led by a decline in mainland Chinese sightseers

- While the national security legislation might lure arrivals from across the border back, what impact will it have on those from further afield?

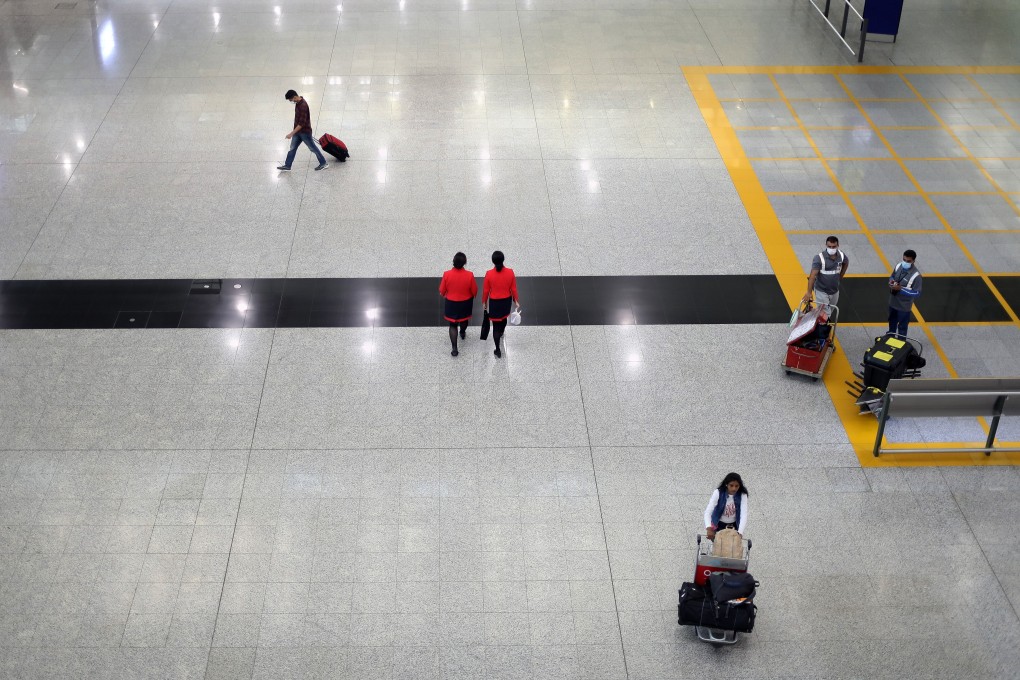

What a difference 12 months make. In June 2019, as hundreds of thousands, maybe millions, of Hongkongers took to the streets to demonstrate against a proposed extradition law – marking the first of not one but potentially three city-changing events to occur within a year – more than five million people arrived in the city. According to the most recent data from the Hong Kong Tourism Board, just 4,125 people entered this April, marking a 99.9 per cent decline on the previous year.

Of course, with the global tourism industry all but paralysed by the coronavirus pandemic and Hong Kong’s borders essentially closed to outsiders, that most recent slump is far from startling. More worrying for those who rely on the city’s tourism industry – which accounted for about 7 per cent of total employment in 2017, according to government figures – should be that visitor numbers started slipping back in July.

That downturn was driven by the loss of mainland Chinese visitors crossing the border, day trippers and overnighters alike, who have long been the bread and butter of Hong Kong’s tourism industry, even if their presence has sometimes been bittersweet. But arrivals from further afield dwindled, too.

A correlation can be seen between the growth in protests and the slump in arrivals. As scenes of violence played out on the streets, in MTR stations and at the airport – and prominently in international media – visitors began to question whether the city was safe. It seems unlikely Beijing’s national security law will convince would-be visitors, at least those outside mainland China, otherwise.

But do those from outside China matter to the recovery of Hong Kong’s tourism industry? Of the more than five million arrivals in June last year, 78 per cent came from across the border. As Benjamin Quinlan, chief executive of consulting firm Quinlan & Associates, told travel news website Skift: “Ultimately, if the [national security] legislation can restore a sense of calm to the city, that would be a big plus for travel […] We could see a decent uptake in the return of travellers from the mainland.”