Britain soon forgot a diplomat murdered in China, but locals in Yunnan remember story of his killing 125 years later

- In 1875, British consular official Augustus Raymond Margary was killed near the backwater town of Tengyue close to the border with then British-ruled Burma

- More than a century later, a writer hunts down the remaining traces of the incident in and around modern Tengchong

On January 3, 1875, 28-year-old Augustus Raymond Margary arrived at Tengyue, a small fortified town in China’s western Yunnan province, close to the border with British-controlled Burma.

Margary was a British consular official from Shanghai and his six-month cross-country journey, by boat up the Yangtze River and then overland through territory he was perhaps the first European to see, was remarkable. His task was to meet a trade delegation from Burma, travelling on passports provided by China’s Qing overlords, and to act as interpreter.

His own Qing passport had been sufficient to cow a hostile populace and provide safe passage, but the British authorities had so little confidence in Margary’s success they sent a backup interpreter by sea.

They were wise. A few weeks later, Margary was murdered on the orders of local officials.

Now long-forgotten, his death had major political repercussions. The British minister in Beijing, Sir Thomas Wade, took the opportunity to demand financial compensation and to press for the opening of more treaty ports to foreign residence.

The British determination to promote trade between Burma and China meant backwater Tengyue (now Tengchong) would become one of China’s more improbable treaty ports. From 1899 it had a British consul and then a foreign-run customs office to manage commerce that never materialised, and Tengyue’s foreign population remained in single figures. Invading Japanese forces closed the consulate in 1942.

In 2000, I arrived in modern Tengchong to see if any trace of the isolated foreign community remained and whether I could find the site of Margary’s death.

Twenty years ago, not all of the ramshackle town’s streets were paved and much of its limited activity happened around a jade market. In 1900, Scottish geologist Robert Logan Jack had passed through on the run from the Boxer rebellion and remarked, “The principal industries of the place are jade-cutting and jade-speculation.” Little seemed to have changed. Members of ethnic minorities who might be from either side of the border accosted me to sell nuggets of soft green.

Few foreigners passed this way after Margary, but most of those who did wrote books. They all reported attracting crowds of the curious, and foreigners in Tengchong were still sufficiently rare that I heard shouts of “Laowai!” (“foreigner”) and “Helloooo!” at every turn.

When I bought some maps at the Xinhua bookstore and asked about the location of the former consulate, a small crowd gathered to discuss the matter. But no one had any answers.

The city walls and gates were long gone, but the map still showed a district called Ximen (“west gate”), so I walked over, taking a muddy street that might have run parallel to the vanished walls. It was a cacophony of light industry, with tiny shops selling coils of wire and steel tubes, and light trucks puffing out black smoke. I was about to abandon the search when I glanced left into an entranceway and did a double take.

Far across a concrete courtyard serving as a grain and oil market was a battered two-storey building. Its steep roof was of curved Chinese grey tile, its eaves supported by a frame of poles surrounding its stone walls. But poking through its ridge were solid rectangular stone chimneys, and the framework encased a sturdy English cottage to which the Chinese roof was clearly a later addition.

Its walls were pockmarked and the remains of now redundant downspouts had been made sieve-like by bullet holes. The interior was being used to store grain, and an upper storey was reached by a rickety wooden outside staircase at the rear.

This was a real find.

Much of the border with Burma was undefined until a treaty of 1886 between the British and Chinese, which left several ethnicities, particularly the then head-hunting Wa, divided between the two countries, a matter of continuing discontent. Towns and villages in the area were mostly referred to by their Burmese names. Manwyne, in various spellings, was, according to several accounts, the nearest settlement to the site of Margary’s murder.

Unfortunately, many places were transliterated on Chinese maps as Mang-something, older ones using a character for “savage” but modern tact later replacing this with one for a type of grass. The problem was solved that evening by old Mr Dong, at a Burmese-style restaurant run by his daughter. Having saved me from the attentions of curious diners, he sat down for a chat. What on Earth was I doing here?

It just so happened he had once edited a local history book, and solved the Manwyne problem immediately, writing down the characters 芒允 for Mangyun.

Next morning, I secured the front seat on a rattletrap bus that headed southwest on a pretty, winding route over high ground through fields of fluffy yellow rape. At Yingjiang, I was told to go to a different bus station to go farther southwest, and there I was sent outside to find a farm vehicle with two rows of seats in its cab and the characters for Mangyun in the window. This was due to leave “immediately”, which turned out to be only 10 minutes later.

A narrow road of corrugated brick ran along a broad valley, pink-turbaned people working in fields of corn on either side. Mangyun turned out to be little more than a crossroads. The few other passengers – heavily tanned, blue-jacketed farmers – looked at me expectantly. “You won’t know,” I said in Mandarin, “but over 100 years ago an Englishman was murdered near here.”

To my astonishment one farmer turned to the driver: “Does he mean Ma-jia-li?” The others also chanted, “Ma-jia-li, Ma-jia-li.”

“I know where that is,” said the driver and at no extra cost dropped me 2km further on, at a bend in the road as it ran down to a river. A plain stone in a field to the left, erected in 1986, was carved with large characters: “Site of the Margary incident”. Margary might have been forgotten in England, but he was remembered in China.

British explorer William Gill, passing by in 1877, said the site of the murder was down by a river, but most others, including Australian G.E. Morrison in 1894, later to become Beijing correspondent of The Times, said the spot was under a large banyan tree.

There was indeed a big banyan across the road, sheltering a collection of larger and more elaborate monuments that dwarfed the one to the dead interpreter. Some were memorials to the local people’s struggles against the Japanese in World War II. But another, erected in 1998, was dedicated to the incident.

What was commemorated on the newer marker was not Margary’s death but a subsequent attack some hours later on the small force accompanying the trade negotiators. Sikh and Burmese soldiers, led by three British officers, drove their attackers off, but according to the inscription, “the masses of every ethnicity” united in confronting Margary, “who was leading an invasion force”.

Margary shot first, claimed the inscription, filling the masses with moral outrage so they drove out the invading forces. Some 125 years after his killing, Margary was being made part of a fictional anti-foreign narrative aimed at uniting the ethnic minority groups in Yunnan behind the Communist Party.

When I returned to tell Mr Dong of my success, he showed me his Tengchong history, which told the same story.

Before leaving the area, I visited the well-preserved brick courtyard houses of prosperous Heshun village, whose inhabitants had ventured overseas and made good, sending funds home. Everywhere there were ornate entrances, attractive winding lanes and picturesque views. An elegant library smacking of Victorian England had walls lined with photos of tour groups of returnees.

When I asked a librarian about the building’s origins, he gave me directions through the winding lanes to the home of kindly, retired Mr Zhang, whose father owned the village’s first photo studio.

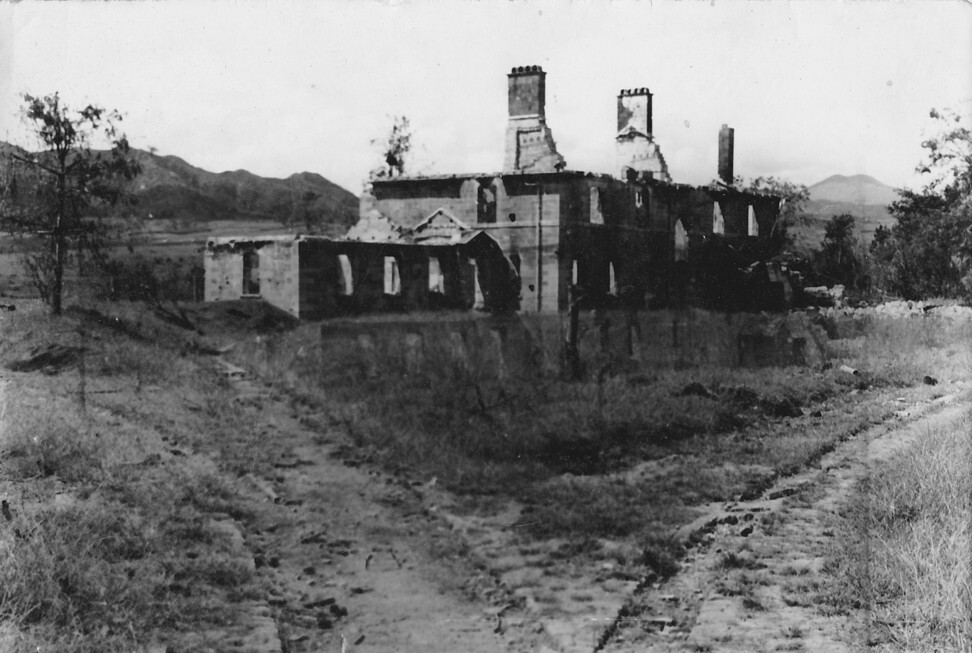

Among the many ancient images he showed me that afternoon, one particularly caught my attention: the burned-out, roofless shape of the former consulate, chimneys and all, sitting amid long-vanished fields, and photographed after intense fighting against the Japanese, who had made it their local headquarters.

This was the building I had chanced on in Ximen – and to my delight, Zhang made me a gift of the print.