The fantastical adventures of Annie Londonderry, the ‘first woman to cycle around the world’

- In 1895, American Annie Londonderry made headlines by becoming the first woman to cycle around the world. Except she didn’t

- A century later, the devout Jewish wife and mother’s great-grandnephew has revealed her true story

In September 1895, a 20-something American mother-of-three named Annie Londonderry became the first woman to ride a bicycle around the world. Except her name was not Londonderry and she hadn’t pedalled nearly so far as she’d led everyone to suppose. She was a brilliant – and unabashed – self-publicist, who briefly turned herself into one of the first ersatz celebrities of modern times.

Returning to her family in Boston after 15 months in the saddle, she soon faded into obscurity and would have remained there had her great-grandnephew – Massachusetts-based Peter Zheutlin – not decided to investigate her epic story.

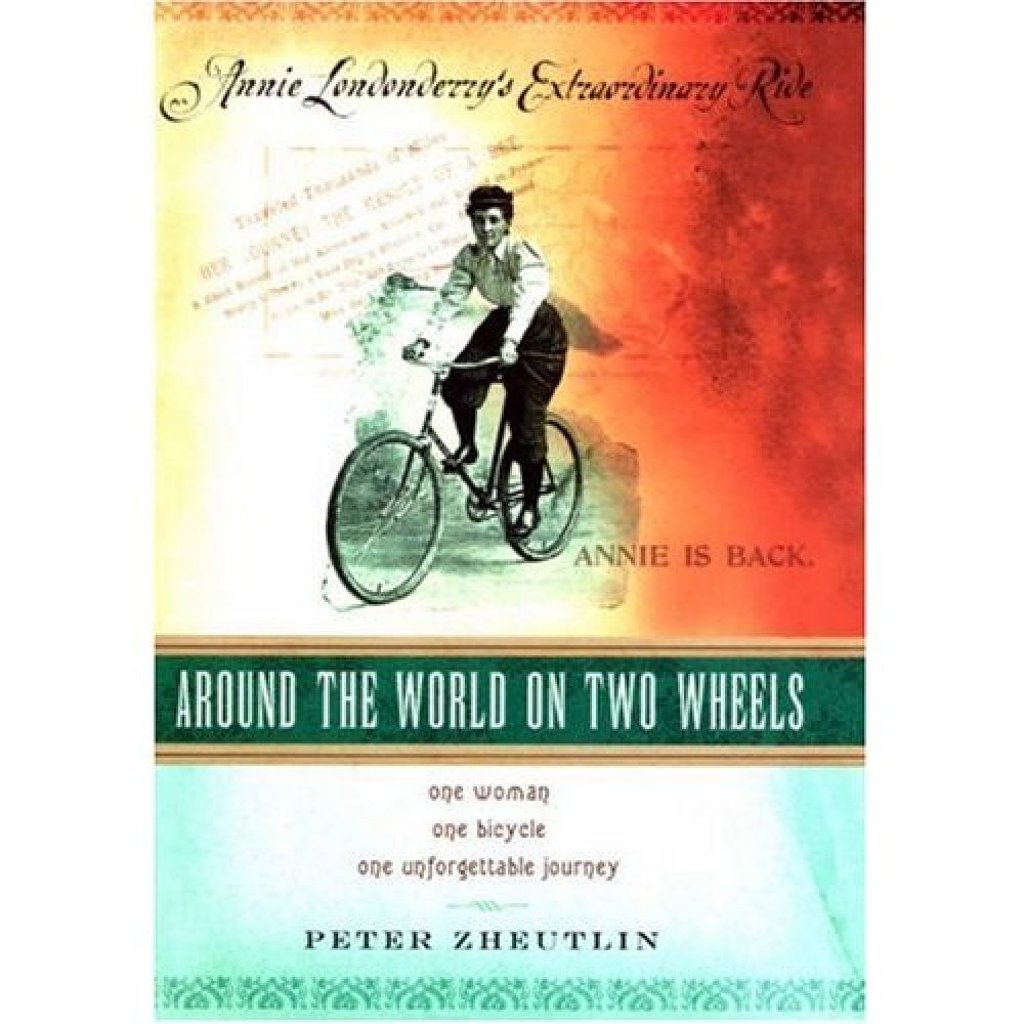

“Annie was an outstanding achiever, but she had a rather casual relationship with the truth,” says Zheutlin, who published Around the World on Two Wheels – Annie Londonderry’s Extraordinary Ride in 2007, three years after embarking on his quest.

“Her accounts of her odyssey were often wildly inconsistent. In a single day she told one reporter she had cycled overland to China from India, and another that she’d gone by steamer. She variously claimed to be an orphan, a lawyer, a medical student, an accountant and an heiress – and she didn’t always own up to being married either.”

Born in Latvia (then part of the Russian Empire) in 1870, Londonderry emigrated to the United States with her parents five years later. Her real name was Annie Cohen Kopchovsky, but she changed it at the start of her cycling trip, after brokering a sponsorship deal with the New Hampshire-based Londonderry Lithia Spring Water Company.