Indonesian Instagram influencers swimming with horses gave remote luxury resort hope amid the coronavirus lockdown. With travel ban it’s back to survival mode

- The US$1,500-a-night Nihi Sumba resort on a remote island lost its customers when Indonesia closed its borders early last year

- Nihi Sumba cut back staff, increased recycling and efficiency, and was surviving on a quarter of its usual income until new Covid-19 curbs came in

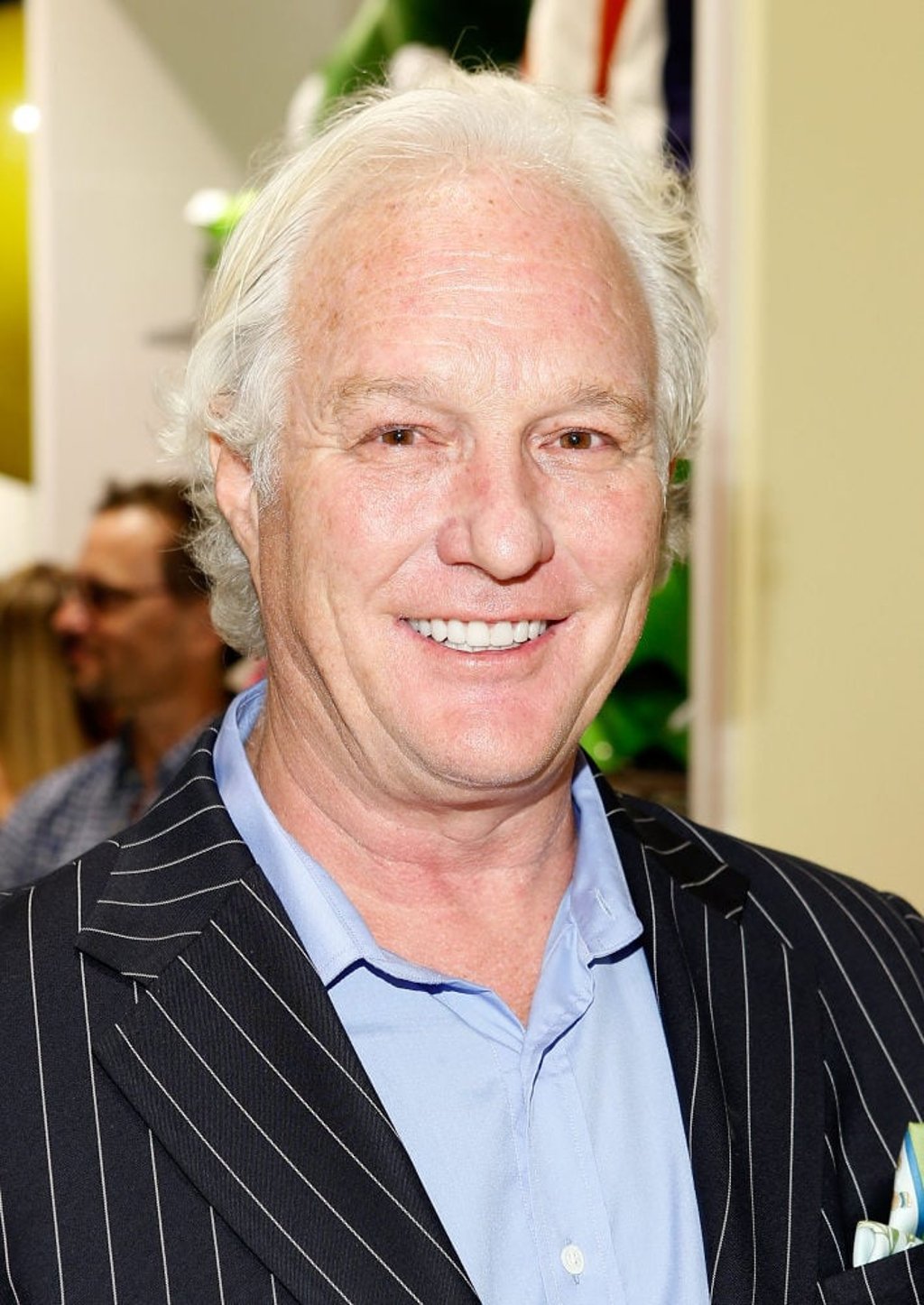

With investments in property, building supplies, phone gadgets, dotcom start-ups, city hotels, fashion and celebrity lifestyle brands, Miami-based financier Chris Burch enjoyed a winning streak in business that earned him a seat at the billionaires’ club in 2012.

But when he bought Nihiwatu, a high-end surf resort on Sumba Island, 800km east of Bali, for US$30 million in the same year and began sinking millions more into expanding it into a family-friendly ultra-luxury hotel, the consensus was that Burch had finally misstepped, with an irrational, emotionally driven investment.

“I bought it to spend quality time with my sons,” he tellingly said at the time.

Anyone who’s stayed at the property, now called Nihi Sumba, can relate to those sentiments. With 17,000 islands, Indonesia has no shortage of beaches, but the 2.5km arc of sand the resort has exclusive access to is something else, backdropped by a ridge of impenetrable jungle, with endless barrelling waves and statuesque rock formations resembling giant discarded chess pieces.

“You can feel it when you come here. It’s a sacred place,” says the property’s founder, Claude Graves, who still lives close by.

Comprising 22 hectares of manicured gardens that conceal 33 pool villas, Nihi Sumba is a tropical maze scented by frangipani blossoms. Add a small army of butlers, a chocolate factory for the children, a stable of Sumbanese horses, jet-skis to chauffeur surfers out to reef breaks and nature-based experiences such as kayaking down a gin-clear river and riding horses in the surf, and one begins to understand how the property, which is nowhere near as fancy as a Ritz-Carlton or the like, was able to charge an average room rate of US$1,500 per night.