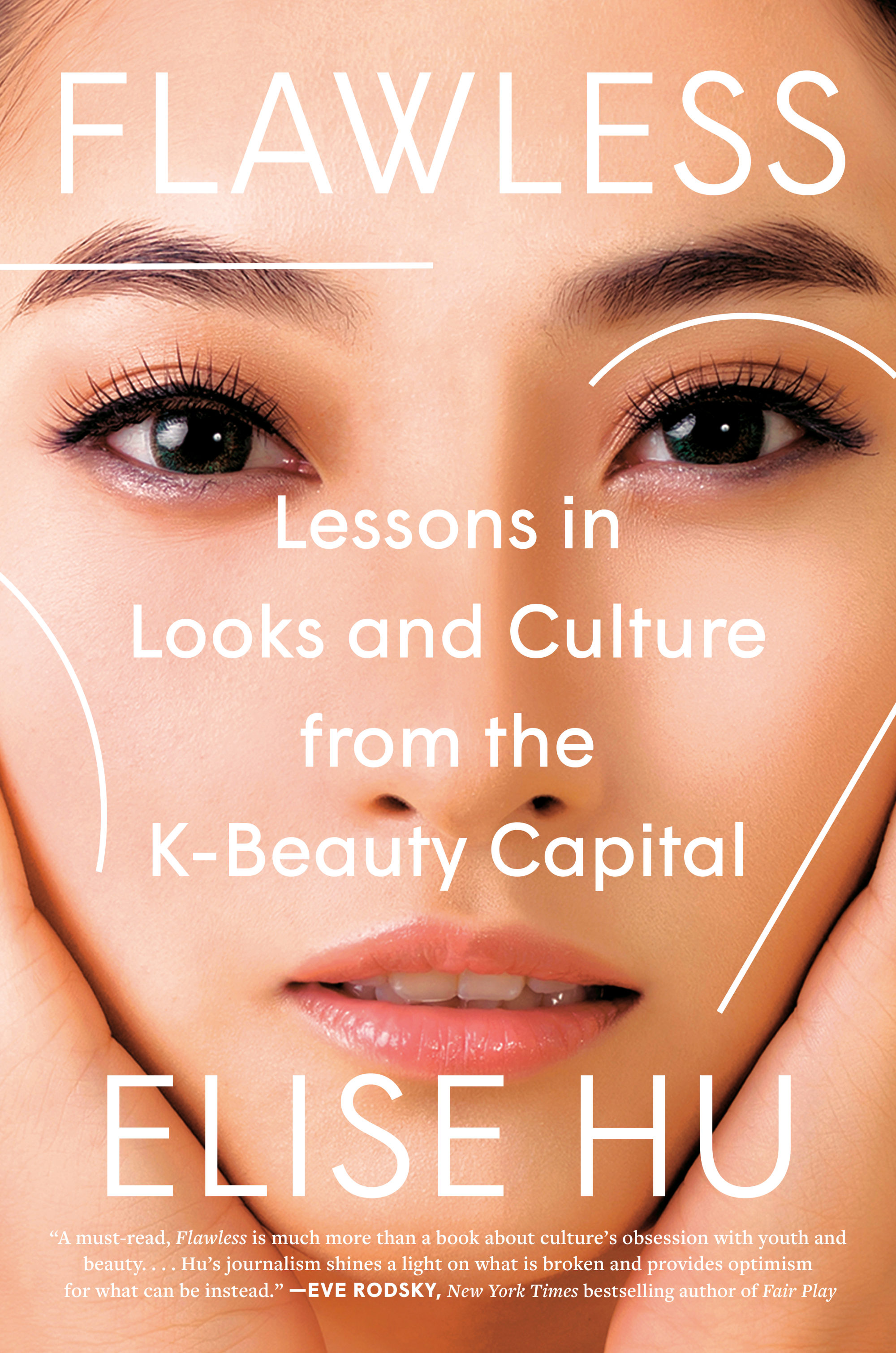

What Elise Hu’s book Flawless reveals about K-beauty: after living in Seoul, the Asian-American reporter holds a mirror up to South Korea’s beauty standards and obsession with cosmetic surgery

Elise Hu landed in Seoul in late 2014 and felt almost immediately that she wasn’t quite good enough.

Hu’s personal experience with the unyielding rigidity of beauty standards in South Korea led to her book Flawless: Lessons in Looks and Culture from the K-Beauty Capital, which she describes as “part memoir, part social commentary, part reporting”.

The Los Angeles-based journalist and podcaster – she’s a correspondent for Vice News and a host-at-large for NPR – was NPR’s first-ever Seoul bureau chief from 2015 to 2018. Flawless is the result of that time there, although Hu says she “didn’t realise I had a book in me until after I repatriated to the US”.

10 Asian stars rocking Barbiecore in 2023: from HK’s Grace Chan to Blackpink

“The rigidity of the beauty standards in South Korea and the expectations foisted upon women in East Asia were apparent to me pretty early on,” she said. “It was in the comments people would make, and the prevalence of images and ads and the consumerism around beauty, with everyone trying to reach certain beauty standards.”

Flawless is written in a chatty, candid style, packed with as many anecdotes as hard facts, all pointing to the culture’s obsession with beauty. Hu, who arrived in Seoul with her husband and toddler daughter, visited the teeming Myeongdong shopping district and wrote that there were “so many skin care and make-up stores that I could stand on a corner and see a Face Shop across from a Face Shop across from a Face Shop. It was common to spot women walking around with silicone nose covers and medical tape, following cosmetic procedures”.

She recalls that everywhere she turned, she was “assaulted with an endless barrage of images of women – huge, very zoomed in, floor-to-ceiling images of their faces. That really threw me. Advertisements in the US and Europe feature more diversity just by dint of the population. They also don’t just feature people. But in South Korea, ads feature just celebrities and their faces, and if not a celebrity, then a beautiful person”.

Which face oils should I add to my skincare routine? From baobab to moringa

Hu interviewed hundreds of girls and women – aged 7 to 73 – about their beauty ideals. What she came away with was that the mass obsession with beauty in the culture is “considered normal and natural”.

“The more those beauty ideals get embedded – that to look good equals a good life – the more that notion gets normalised and the more that the idea of trying to fix your face and body goes unquestioned,” she said. “Upgrading and changing your body becomes a personal responsibility, and if you don’t do it then you are lazy and not taking advantage of your economic privilege.”

During Hu’s time in Seoul, she was also exposed to the other end of the spectrum – a rise in feminism after the 2016 murder of a woman who was fatally stabbed by a homeless man because of her gender. The subsequent feminist tide resulted in women cutting their hair short, wearing gender-neutral clothes and crushing their powder compacts.

Hailey Bieber just rocked the brewing latte make-up look – all over her body

“There was a general strike against aesthetic labour, with women saying, ‘I’m not going to be a part of this any more.’” Many were disowned by their families for renouncing femininity, others were bullied, “because the position they take is considered by Korea’s mainstream as radical. They pay a high psychological tax for trying to opt out”.

It wasn’t until Hu returned to the US that the idea for Flawless settled in. She had two more daughters while living in Korea, and she realised that one of the three phrases her girls knew in Korean was ‘you’re so pretty’. That struck a particularly deep chord with Hu, who recalls that growing up in Dallas – an Asian girl in the white suburbs in an red American state – she “never felt particularly pretty”.

“I struggled with feeling worthy,” she said. “The social milieu said that whiteness was pretty.” Although she began modelling as a teenager for catalogues, she developed an unhealthy relationship with her body and food. But she worked her way through it and those feelings subsided … until she got to Korea.

What is skin icing and how does it work? Experts share their tips

“In Seoul, it was as if I was my teenage self again. All those feelings of self-consciousness, of taking up too much space, they all came back,” she admits.

With Flawless, Hu hopes to make the point that how women feel about themselves governs everything … “whether we raise our hands in class, whether we leave our house for parties or meetings, whether we try new things or run for an election”.

“I know I haven’t shown up as my truest self because of my own body image,” she says. “And if you multiply that experience by the millions of women and girls out there, we are talking about a real missing swathe of opportunity, and missing magic that can be put into the world.”

- The Vice correspondent and NPR host was the latter’s first-ever Seoul bureau chief – but felt uncomfortable with the culture’s wide use of facials, lasers and injectables

- Her book draws on personal observations, such as how Myeongdong shopping district is full of skincare and make-up stores like Face Shop, with every ad featuring close-ups of beautiful people