Opinion / Does Bruce Lee’s legacy have a dark side? His peerless kung fu paved the way for Jackie Chan and Jet Li, but that violent image may have typecast Asian action stars forever

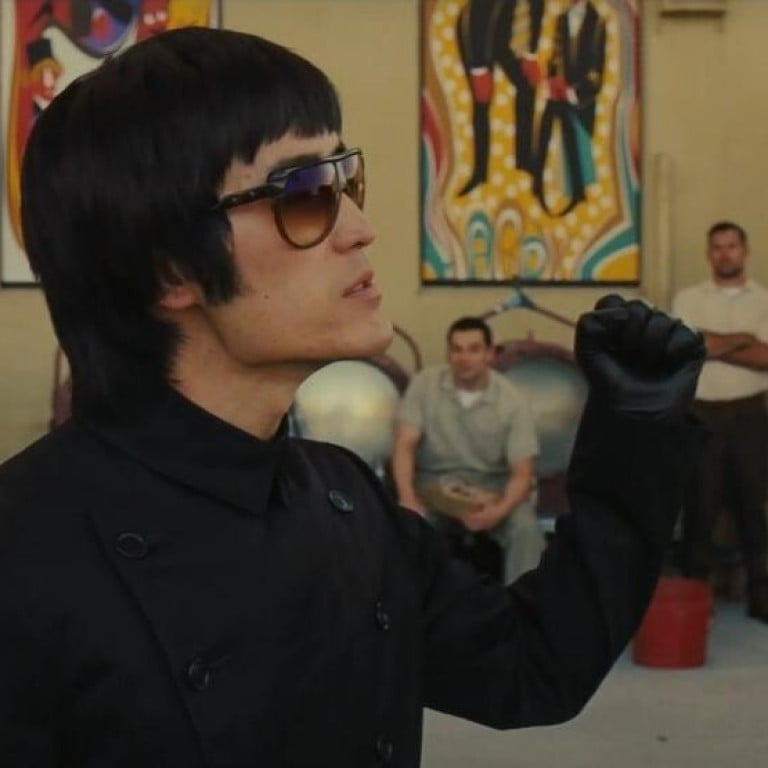

He inspires millions to this day, but Lee’s legend has a dark side probed by Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood – can the martial arts icon’s hyper-violent, highly fetishised image really be blamed for holding Asian actors back in Hollywood?

Earlier this year Shannon Lee, Bruce’s daughter, talked to the South China Morning Post about the film and discussed the pain that Tarantino’s characterisation of her father caused.

“My feeling is the same. I was very disappointed,” Lee said. “I’m not going to say I wasn’t angry at all, but certainly sitting in the movie theatre and having that experience with an audience was not a fun experience for me.

“I was very disappointed to see Quentin Tarantino’s response, which was to continue to say, ‘Oh, Bruce Lee was arrogant, he was an asshole’, and to incorrectly cite my mother’s book as a defence. I really thought it was irresponsible of him to do what he did and have that portrayal.”

Tarantino received widespread criticism for his depiction of Lee – not just from family members like Shannon Lee, but fans across the world. It’s not hard to understand why. For decades Lee has been heralded as an icon. He did untold good in breaking down barriers for Asians in America.

When Lee started working in Hollywood in the 60s, it was normal for Caucasians to play Asian characters – this was the same decade, remember, when Mickey Rooney played the racist caricature that was Mr Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Lee came along and changed that. Suddenly, an Asian character like Kato, in The Green Hornet, could actually be played by an Asian actor. In an era where white folk were always the hero and people of colour were often the first to die in Hollywood films, Bruce Lee stood tall, not only surviving but saving the day along the way. When Lee defeats Chuck Norris in the Coliseum at the climax of The Way of the Dragon, he represented all people of colour still fighting wars against Western imperialism.

Given the hagiographic nature of much of the coverage surrounding Lee, I was surprised to come across a work that suggested there might be negatives to Lee’s legend. The work in question was Paul Bowman’s scholarly text Theorizing Bruce Lee: Film-Fantasy-Fighting-Philosophy.