Are LGBT K-dramas just queerbaiting? Shows like Netflix’s Vincenzo and Mine are featuring more gay characters but South Korea’s showbiz still has a way to go

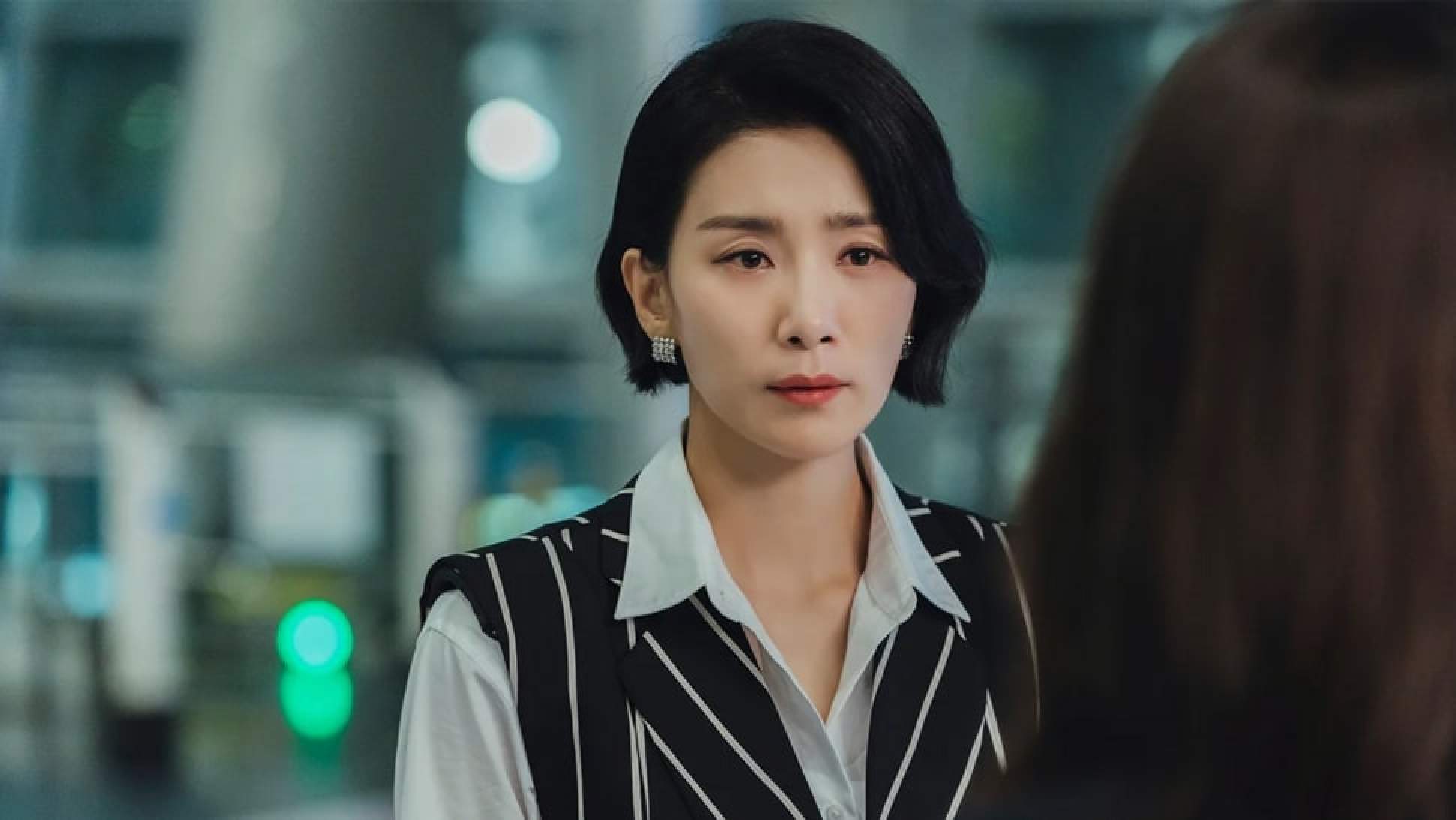

When we talk about LGBTQ+ representation in Korean pop culture, films have fared way better than the small screen. For example, two of 2016’s queer films, In Between Seasons and The Handmaiden, earned rave reviews from critics and audiences alike for their authentic storytelling, but K-dramas surprisingly lag behind. In general, the TV shows still perpetuate tired gender stereotypes and under-represent LGBTQ+ lives in their plots; if there are any queer characters, they are most likely to be token, inauthentic portrayals.

As Korean entertainment has risen to dominate global culture, catering to a wide, diverse range of global audiences, can beloved K-dramas truly promote better visibility for their LGBTQ+ characters, or will they merely capitalise on marginal communities by featuring them, just to be seen as “woke” and internationally appealing?

Here’s a quick look at the history, struggle and changes of LGBTQ+ representation in K-dramas.

14 new Korean films to watch in 2022 – plus 2 actors’ directorial debuts

Media censorship and public backlash

At the recent New Year’s Eve bell ringing ceremony in South Korea, dance group Lachica performed a watered-down version of Lady Gaga’s queer anthem Born This Way, which was met with an uproar from the community that embraced it. This version omitted the crucial lyrics, “No matter gay, straight or bi, lesbian, transgender life”, drawing accusations of LGBTQ+ erasure.

Media censorship is not uncommon in South Korea, especially when it comes to LGBTQ+ characters. In 2010, a romantic vow between two male characters in Life is Beautiful – regarded as Korea’s first drama to feature a gay couple – was censored after the church where the scene was filmed filed a complaint with SBS. The show’s progressive take on gay relationships also angered the public. A national mothers’ group ran a discriminatory newspaper advertisement that said, “When my son becomes gay and is inflicted with Aids watching Life is Beautiful, SBS should take the blame,” according to Korea JoongAng Daily.

Another example came in 2014 when JTBC received a warning from the Korea Communications Standards Commission after it showed two female high school students kissing in the drama Schoolgirl Detectives, saying the scene “broke moral standards”.

However, the censorship received some backlash as well. Life is Beautiful’s showrunner and veteran writer, Kim Soo-hyun, voiced her anger in Korea JoongAng Daily over the censorship on her show. “A cathedral is a place where even a murderer can find sanctuary – but I guess gays can’t. Actually, I was more angry at the television network, because it should be the one doing all it can to alleviate discrimination, not chickening out.”

Meet Cha Hyun-seung, heartthrob of Netflix’s Single’s Inferno

Bromance or queerbaiting? Capitalising on discrimination

While some show writers like Kim have helped promote queer visibility on screen, over the decades we have also seen an increasing number of “queerbaiting” subplots in the form of bromance comedy in Korean shows. Queerbaiting generally refers to strongly hinting at a gay relationship between characters in order to appeal to LGBTQ+ viewers and capitalise on their interest, but without actually following through on the initial depiction – or sometimes even turning it into a joke.

The 2017 drama The Boy Next Door tells the story of two attractive singles (played by Choi Woo-shik and Jang Ki Yong) who are flatmates mistaken for a gay couple. The show featured many comical, suggestive and homoerotic scenes that encouraged the audience to imagine the two characters having a same-sex relationship, but the show never writes them as an actual gay couple. (Although it did feature a supporting role who came out as gay and proud in one episode.)

Meet Cha Hyun-seung, heartthrob of Netflix’s Single’s Inferno

The “boys’ love” era: Korea vs the rest of East and Southeast Asia

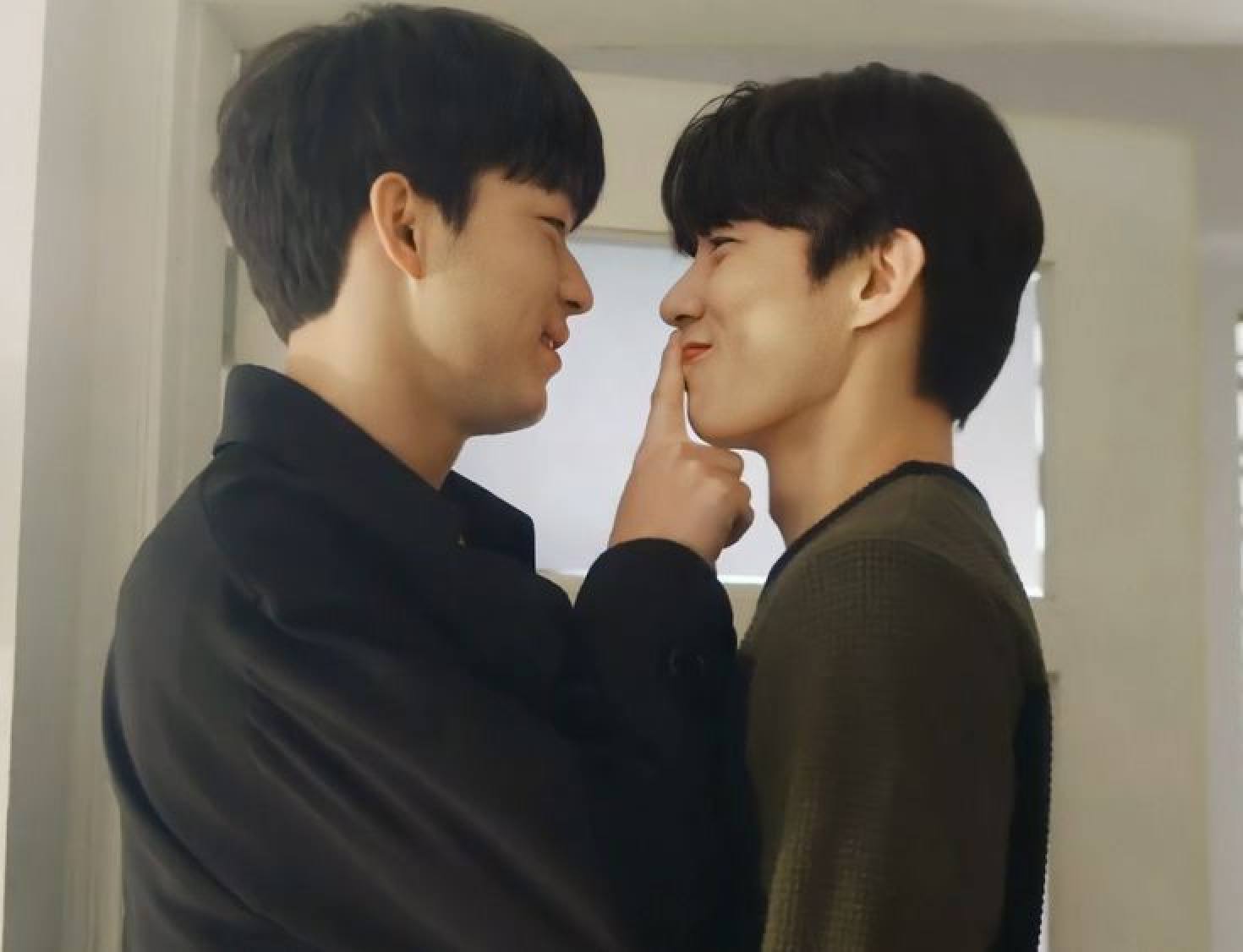

The 2020 Korean web series Where Your Eyes Linger was dubbed the first “real” BL by fans, with its plot centring on the relationship between a young chaebol (conglomerate) heir and his bodyguard. There are also other titles like To My Star, Wish You and Nobleman Ryu that will satisfy fans who prefer more idyllic gay romances set in fictional worlds where being gay is not frowned upon.

Without a doubt, BL brings a breath of fresh air to Korean TV, although not all members of the LGBTQ+ community are in favour of it. The reason? Many BL series are supposedly written and consumed by straight women who enjoy stories about gay male relationships. Some readers and viewers argue that the BL genre results in flat, one-dimensional depictions, while others believe that if straight women create and consume content about gay male characters, the practice is automatically fetishistic. (However, since coming out as LGBTQ+ presents difficulties in many Asian nations, we can’t dismiss the possibility that some of these creators may be closeted members of the community themselves.)

7 Korean stars born in the Year of the Tiger – and how their 2022’s looking

Visible representation and anti-discrimination law

A 2021 Time article reports that, “according to a survey by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea, seven out of 10 South Koreans believe that it is wrong to discriminate against sexual minorities and nine out of 10 support the enactment of a comprehensive anti-discrimination law.”

However, anti-discrimination legislation in South Korea was recently postponed to May 2024 by the country’s National Assembly, even after an online petition in favour of it received over 100,000 signatures last year, and various other bills have been tabled since 2007.

“I don’t think the problems have been solved, but I feel there is less of a comical depiction of sexual minorities. However, this might be caused by society being more cautious about stereotyping genders, rather than the underlying hate for sexual minorities diminishing,” said one gay rights activist to Korea Herald.

- Korean films In Between Seasons and The Handmaiden earned rave reviews for authentic queer characters, but many K-dramas feature token or even negative portrayals – like Squid Game

- But media censorship is still a problem – a dance group performed a sanitised version of Lady Gaga’s anthem Born This Way for the New Year – and so is the lack of anti-discrimination laws