‘Russia leather’ is coveted by luxury brands like Moynat and Hermès

For centuries, one of the most sought-after secrets within the fashion and historian community alike is an age-old leather tanning process that rests at the bottom of the English Channel as part of an abandoned shipwreck from 1786. Hours after the 53-tonne brigantine Die Frau Metta Catharina set sail from St Petersburg with bundles of leather, a storm sank the ship to a depth of 30 metres off the southwest coast of England.

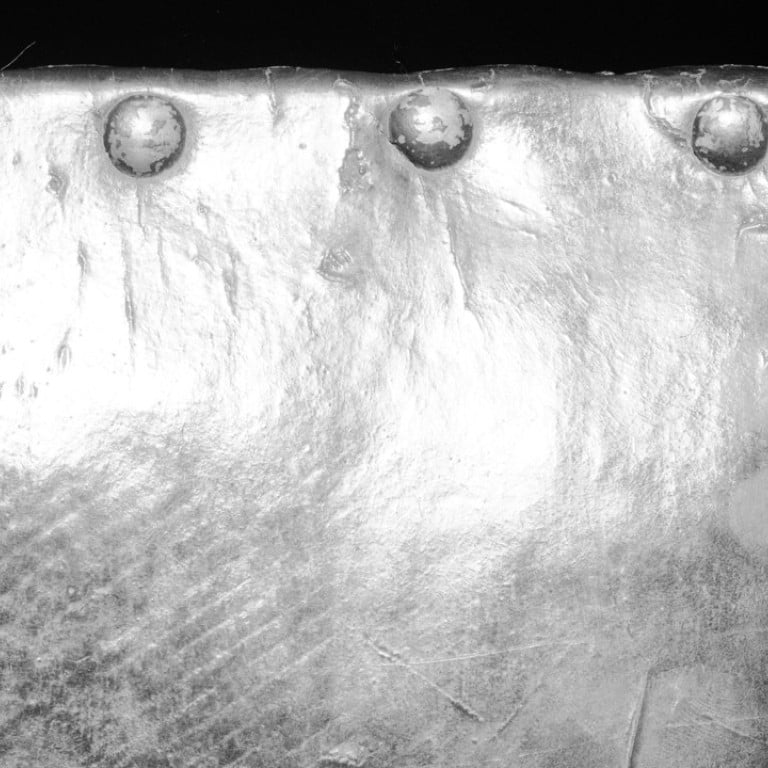

The wreck, along with the leather, remained undiscovered at the bottom for close to 200 years. But in 1973, when a team of archaeologists came upon the Genoa-bound ship’s remains, local tanneries and museum curators flocked to gather the pristine hides uncovered with the ruins known as “Russia leather”.

Native to 17th century Russia, the hides were created from a meticulous three-step process that involved months of tanning, oiling and dyeing. Its distinctive characteristics, such as a specific shade of dark red, supple texture, resistance to water and insects, and a diamond cut hatching, turned it into a must-have luxury item back in the 17th century.

Over the years multiple failed attempts were made at replicating the stealthy process once used by Americans to upholster seating furniture, create luxury footwear, belts, and even a specific perfume.

Sadly, all that remains is the small batch salvaged from the shipwreck and sold to museums and brands for preservation as well as recreation of new styles.

Winterthur Museum of Delaware is among the few lucky procurers of whole hides preserved as artefacts and also cut up and used for historic upholstery. “Production of the 18th century type leather seems to be a lost art. Following closely-guarded secret processes, Russian tanners made Russia leather from reindeer hide, soaked for many weeks or even months in a tannin bath extracted from the bark and leaves of willow, birch, chestnut or oak tree,” say Mark J. Anderson, Elizabeth Terry Seaks senior furniture conservator, and Joshua W. Lane, Lois F. and Henry S. McNeil curator of furniture at Winterthur Museum.

Moynat – the historic leather goods creator acquired by LVMH – announced late last year that they were working to “update” the old formula as part of a new collection. The new line included the label’s iconic “Gabrielle” handbag created in collaboration with Tanneries Roux, a tannery belonging to the LVMH Group, using what they called the “Imperial calfskin”.

“Faithful to its values, Maison Moynat has marked the renaissance of Russia leather with an updated version of this mythic material.

Did it succeed? Although there is no sole authority on this, critics and experts have their doubts.

Emmanuel Guegan, head of accessories at James Purdey & Sons, the British gun maker that specialises in high-end bespoke shotguns as well as clothing and accessories, has worked with the original skins from the shipwreck since its rediscovery in 1973. He explains why whatever little remains is all that is truly authentic and recreation of the technique is impossible.

“Oak bark tanned leather is only produced by a handful of tanneries in the world. It is a very lengthy and chemical-free alchemy-like process,” he says. “Recreation is out of question. You cannot replicate history and provenance. That’s what makes it so special, rare and desirable.”

Smaller brands have since followed in Hermès and Moynat’s footsteps. While some are said to have reinvented the technique, others continue to create pieces from the remains. Marked interest for the material among mainstream luxury is unexpected

and new.

Re-creation is out of question. You cannot replicate history and provenance. That’s what makes it so special, rare and desirable

While both Moynat and Hermès claim it stems from a fascination with heritage and rarity of the technique, a few other factors are seemingly at play.

Luxury revenues took a sharp hit in the aftermath of the terror attacks across Europe amid reduced consumer spending and a radical decline in tourism from China. Luxury brands have employed a number of techniques to recover from the sluggish growth. Renewed interest in Russia leather seems curiously timed though it has generated a lot of consumer interest. In 2017, a little over a year after debuting its “Sac a Depeches” Russia leather briefcase, Hermès reported a 7.6 per cent revenue boost in its fourth quarter sales, fuelled by its mainstay leather goods business.

Likewise, LVMH, which has reportedly committed itself to the “sustainable procurement of skins and leather as well as in-house development of finishing and protective techniques”, also saw an increase in sales this year not long after Moynat launched its Imperial calfskin bags. Much like Hermès, the luxury conglomerate’s most profitable sector apart from apparel is leather or “soft luxury” products.

This isn’t to say that Russia leather alone is responsible for this rise in sales, but luxury’s sudden tryst with the rare material appears to be part of a strategic marketing plan focused on heightening consumer inquisitiveness in leather goods.

The power of history and heritage is what draws people to it

LVMH and Hermès have been in fierce competition with each other and over the years, adapted growth strategies as an attempt to gain leverage over each other. It’s why Hermès’ rare “Sac a Depeches” briefcase preceded Moynat’s Imperial calfskin collection so closely.

Athene English, owner of the online leather goods store The Great English Outdoors, claims to be one of the true admirers of the art and has worked with Russia leather for more than 30 years. The saddler is unfazed by the renewed interest in it. “I have not ‘just’ come upon this leather. I have had the pleasure and privilege of working with it for over 30 years, she says. “However, it is now sadly at an end. I guess it is why people have become so fascinated by it.”

English and Guegan, are among the many Russia leather enthusiasts devoted to its preservation and hope the renewed interest, however fuelled by profitability, can lead to the restoration of the lost art.

“The power of history and heritage is what continues to draw people to it. The emotions triggered by owning a piece of history or relic are part and parcel of the modern luxury industry,” Guegan says.