Discreet wealth: today’s rich show status through elite schools and health care, not designer handbags – why inconspicuous consumption is the true mark of a millionaire

- Elizabeth Currid-Halkett coined the term ‘inconspicuous consumption’ in her 2017 book, The Sum of Small Things: A Theory of the Aspirational Class

- As most consumer goods got cheaper, hospital services, college tuition, medical services and childcare have sky-rocketed in cost – and prestige

Newsflash: showing off your wealth is no longer the way to signify having wealth.

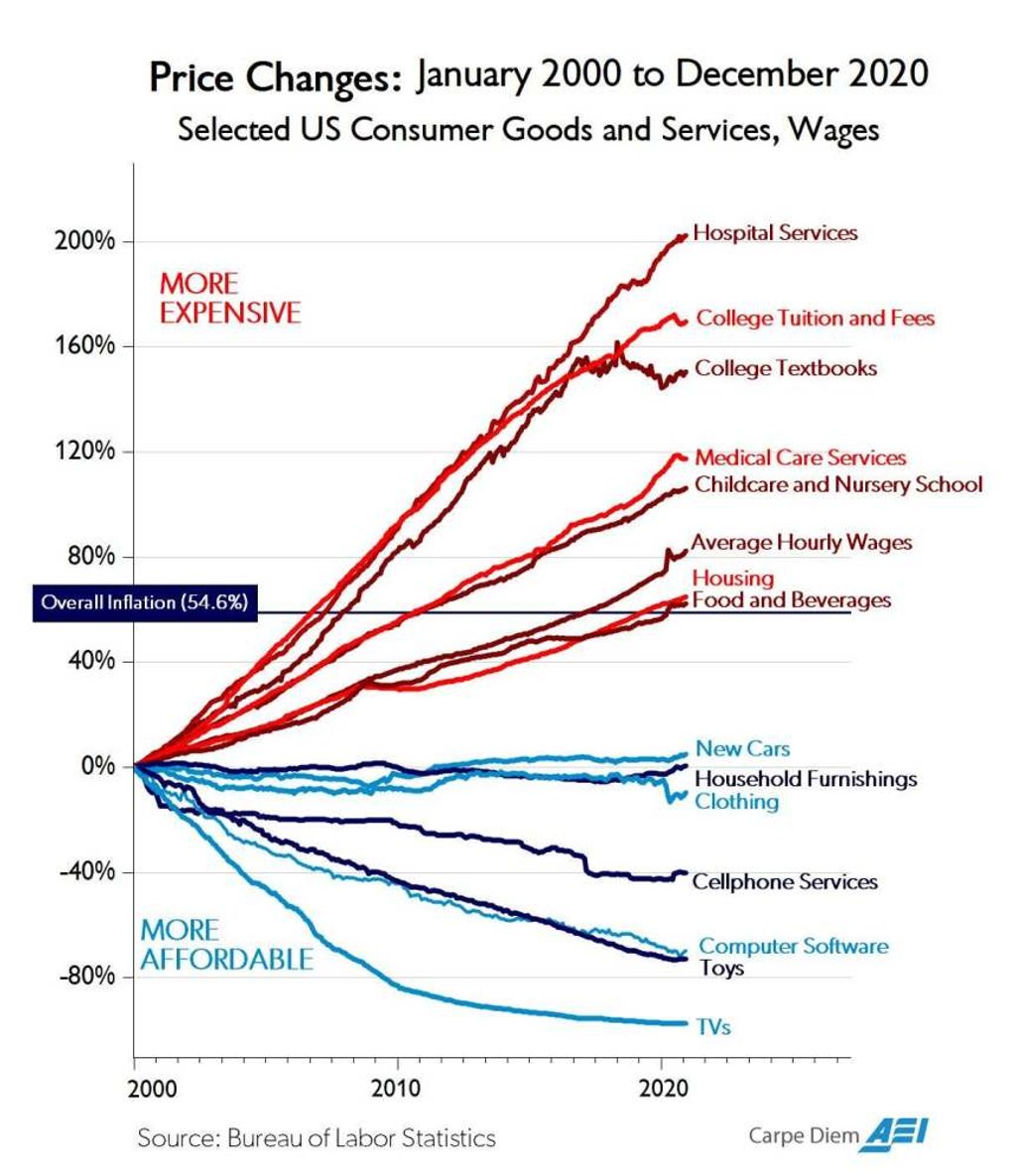

Consider the famous inflation chart by American Enterprise Institute (AEI), which was once dubbed by Bloomberg as the “chart of the century” and has done the rounds on various media platforms throughout the years.

The latest iteration, featured below, shows 54.6 per cent overall inflation over the last 21 years, which works out to an annualised compound growth rate of 2.2 per cent, very close to the Federal Reserve’s stated inflation target.

But as you can see, some services and goods have become way more expensive than others.

Hospital services, college tuition, medical services and childcare have seen disproportionate upticks well above the average 54.6 per cent inflation. Their costs have outpaced the hike in average hourly wages, which have shot up by 82.5 per cent, or 28 per cent more than the average increase in consumer prices.

Meanwhile, consumer goods such as new cars, clothing, computer software, toys and TVs have become more affordable.