Explainer / What are the most common gem setting styles in jewellery? From the popular prong to the bezel, flush, pavé methods, and the Tiffany setting seen on most diamond engagement rings – the ancient art explained

- The setting created by Tiffany & Co. founder Charles Lewis Tiffany is a classic, but pavé is one of the most difficult methods, often used by Graff and Van Cleef & Arpels

- There’s also the bead, burnish, rose head, buttercup, halo, cluster and bar settings – but what does the world’s largest diamond, the 530.2 carat Cullinan I in the British Crown Jewels, use?

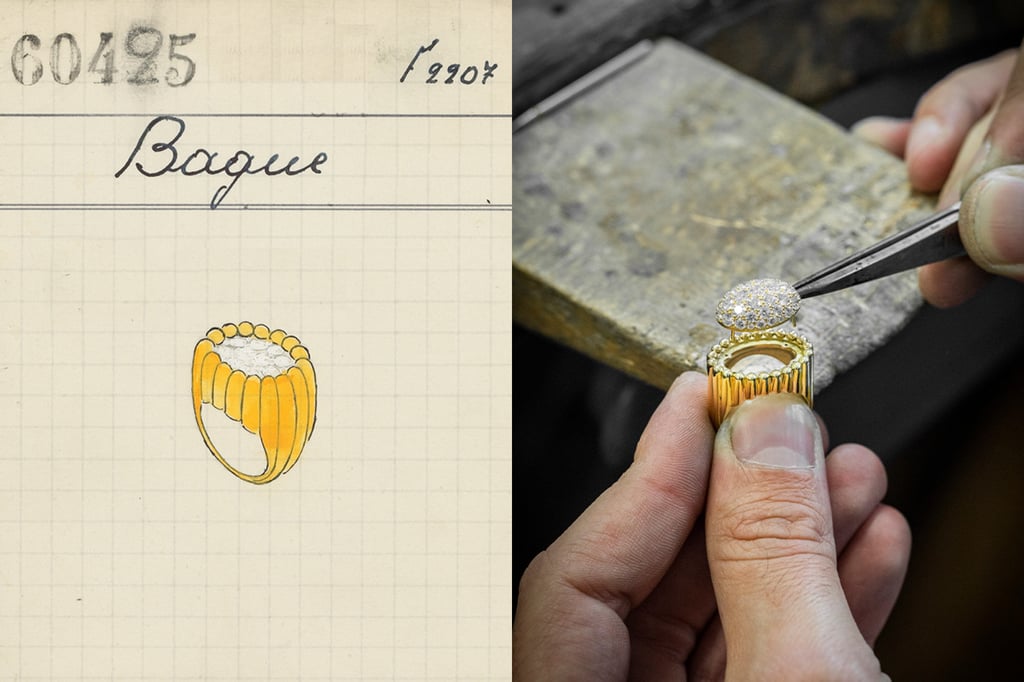

Gem or stone setting is the business of attaching precious stones to metal so that they can be worn as jewellery, and it’s one of the essential skills of the luxury jewellery industry. Depending on the complexity of the setting, the process can take anything from a few minutes to several weeks.

The basic tool of the trade is a rotary cutting device known as a burr, which is used to grind away metal to create the settings. But this is a complicated, technical world full of pushers, burnishers, gravers and bezel rockers, and it takes years of training to reach a professional standard: most stone setters begin their careers with apprenticeships that on average last two to four years before they can work independently.

The tradition of stone setting is a long one: humans have been using gemstones for decoration through all of recorded history, and since the beginning we have mounted these natural marvels on stone and other materials. But sophisticated gem setting techniques, ancestors of the modern day industry, started to emerge around 2,000 years ago, probably on the steppes of Central Asia, with knowledge spreading out both east and west from there.

Among the most difficult of all to create is the pavé setting, which – as the name suggests – seems to pave the entire piece with gems, accentuating their sparkle. It involves laying the stones in holes slightly narrower than they are and securing them with small prongs of metal which are barely visible. The invisible, or mystery, setting takes this even further, with no metal visible at all.

But this is by no means an exhaustive list. There are also bead, burnish, rose head, buttercup, halo, cluster and bar settings, among others.