Neil Armstrong’s bag of moon dust may fetch US$4 million on auction

The bag was used by Neil Armstrong on Apollo 11 to bring back the first samples of moon dust ever collected

It’s the Rembrandt snagged at a garage sale, the Apple Inc. shares found in grandma’s desk.

How ’bout some hints of moon dust? The real stuff. Apollo 11 vintage. Neil Armstrong, 1969.

What might have been a monumental windfall for the man who transformed a planetarium in Hutchinson, Kan., into a world-class space museum (and then served two years of federal time for selling some of its artefacts), or for the Cosmosphere and Space Center itself, instead belongs to a rock-loving lawyer who got lucky with a very overlooked online auction for US$995.

Although NASA never wanted lunar rocks or the moon’s powdery surface traded on the open market, sloppy space souvenir record-keeping a generation ago somehow let a prize slip through.

Later, the lawyer wrestled the bag back from the same NASA folks who confirmed it was laced with real moon bits.

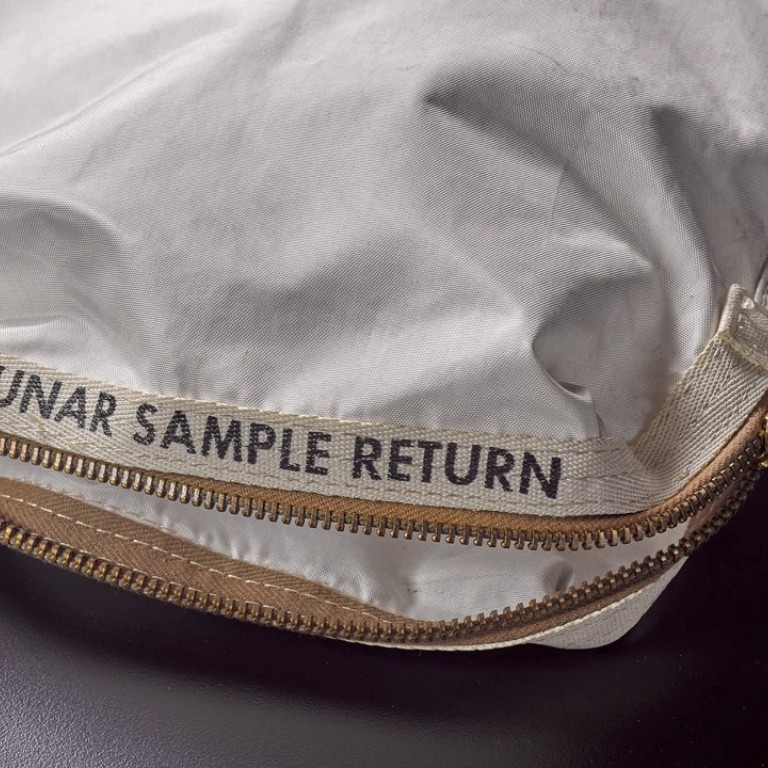

This summer, gilded auction agency Sotheby’s will put that “lunar sample return bag” — an Apollo 11 carrying case still encrusted with moon dust and rocks in its fabric — up for bid. The auction house expects to get north of US$2 million for the moonshot relic.

First-ever moonwalker Armstrong stuck the purselike pouch in a pocket of his spacesuit after taking surface samples following his “giant leap for mankind.”

Scientists back on his home planet would study the dust he stashed away. But the agency that could land a man on the moon couldn’t keep track of everything that was used on the voyage.

The zippered bag would eventually get tossed with other Apollo detritus, work its way to the Cosmophere’s basement and then land in its former director’s garage.

When that museum boss, Max Ary, later was convicted of selling Cosmosphere property and pocketing the proceeds, much of his own space memorabilia was seized, stored for a decade, and then sold to pay his fines and restitution to the Cosmosphere.