Virtual reality and blockchain are taking art to the next level

Art is going hi-tech, and virtual reality and blockchain are in, giving viewers a mind-boggling experience

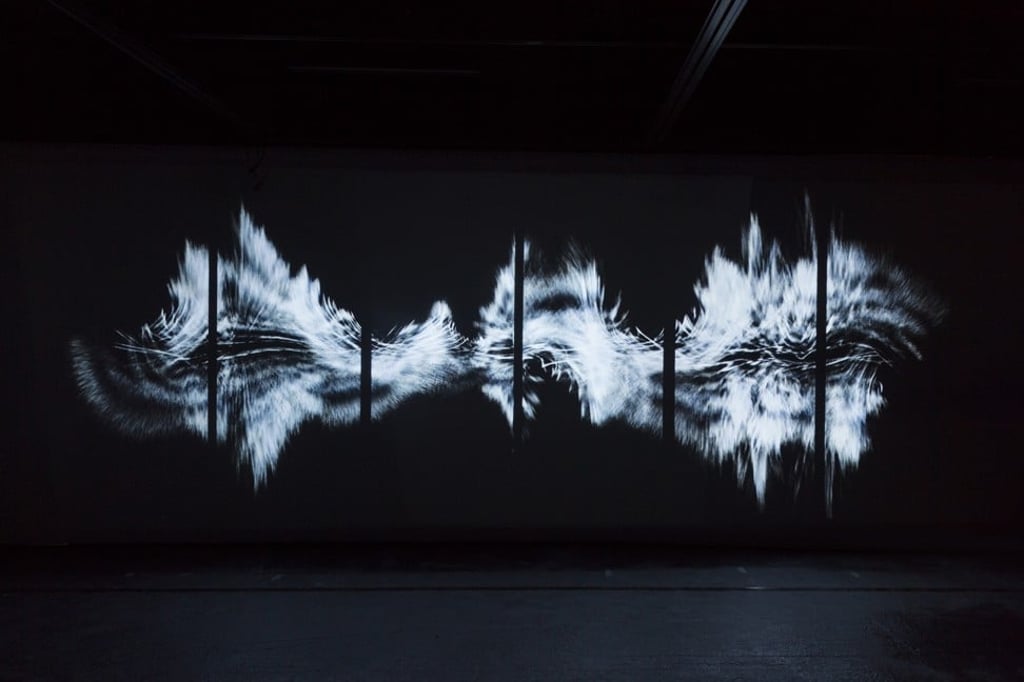

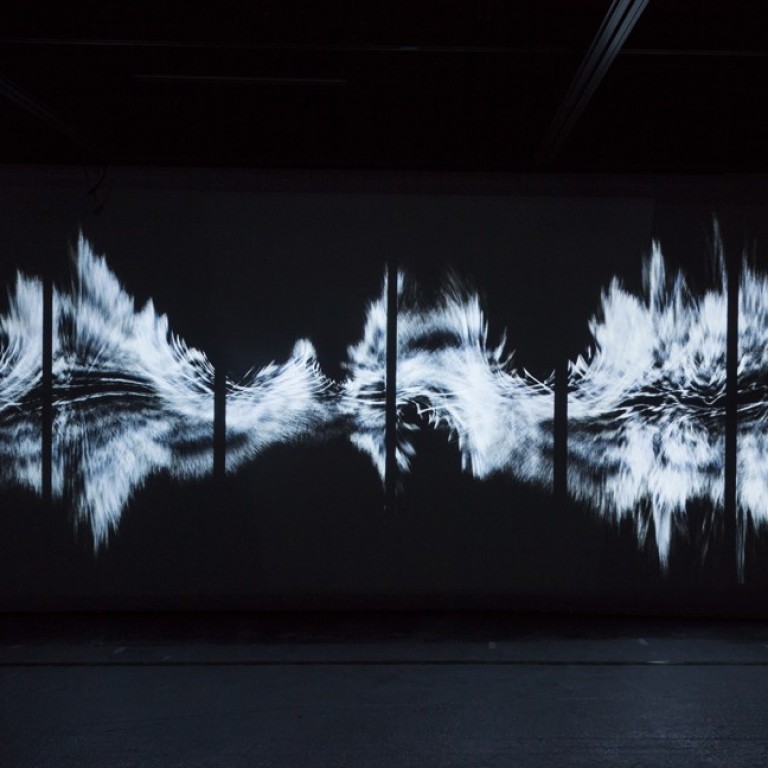

There are strange, sometimes disturbing, new worlds out there. In Jordan Wolfson’s controversial virtual reality (VR) simulation, Real Violence, you’re standing on a New York City pavement watching the artist beat a man to death in front of you. Rachel Rossin takes the opposite tack in Man Mask and leads you on a guided meditation through the video game “Call of Duty: Black Ops” but scrubbed clean of any violence, transformed into a surreal digital paradise.

At Art Basel Hong Kong in March, one of the world’s most respected sculptural artists, Anish Kapoor, reduced viewers to microscopic scale and took them on a tour inside the human body. Other viewers stood by and watched as performance artist Marina Abramovic drowned in the waters of climate change-induced rising sea levels.

Then, of course, there’s the artwork that doesn’t exist at all, neither in this world nor a virtual one: Kevin Abosch, who famously sold a real-life photograph of a potato in 2016 for €1 million (HK$9.65 million), this Valentine’s Day sold the concept of a rose for US$1 million worth of cryptocurrency to a group of 10 collectors. The Forever Rose is an ERC20 token called ROSE on the Ethereum blockchain that is based on Abosch’s photograph of a rose. In other words, the artwork doesn’t physically exist, nor even have a virtual visual representation.

“Potato #345 and Forever Rose pose questions pertaining to identity, existence and value. They are both proxies. The former for the human experience and the latter for love,” Abosch says.

“The Forever Rose, however, is further abstracted from the photographic representation in that it doesn’t exist in a physical sense. It is the result of using blockchain technology to create a virtual proxy of the photographic work.”

So are these technologically advanced works a radical new form of creative output that challenges what we understand as art?

Yes, and no. Dadiani Fine Art in London’s exclusive Mayfair district is possibly the world’s first fine art gallery to accept multi-currency cryptocurrency. When founder Eleesa Dadiani first started accepting Bitcoin, the most well-known decentralised digital currency, she was overwhelmed by the attention – both welcome, and less so.