Millennial money and virtual technologies fuelled a new boom for Chinese art and antiques in the age of Covid-19 – despite closed galleries and cancelled exhibitions

Pandemic, politics and protests have provoked caution in markets worldwide, but an underlying appetite for Chinese art remains strong and younger buyers are increasingly leading the fray

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought much of the global economy to a skidding halt and that goes for the art world, too. This year’s Art Basel Hong Kong was cancelled, part of a sorry trend that has seen the suspension of art fairs, exhibitions and events all over the world. Together these cancellations have left the future of the global art market uncertain.

Despite its standing as the third biggest market in the world, chances of the Chinese art market’s return to the glory days of 2011 – when it overtook the United States with a US$5.1 billion turnover for fine art and antiques – remain slim. While the Asian giant accounted for 18 per cent of the US$64.1 billion that was spent on art last year, according to the latest Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report, there were also decidedly fewer buyers and collectors making bids in Chinese auctions. Political and economic issues, such as the trade war with the US and the Hong Kong protests, have created what Art Economics founder Dr Clare McAndrew described in the report as “a cautious climate for both buyers and sellers”, resulting to a 10 per cent drop in sales in 2019 – a loss for the second consecutive year. Both the US and UK markets also experienced a decline last year.

Yet appreciation for Chinese art – antiques in particular – continues to rise. The most expensive artwork ever sold by Christie’s in Asia is the 1,000-year-old rare ink painting Wood and Rock by Su Shi, which went for just under US$60 million in 2018. Sotheby’s Asia’s highest-value lot in 2019 was a 300-year-old pouch-shaped Beijing enamelled glass vase, which sold in Hong Kong for US$26.4 million. A more recent piece, Chinese-French painter Zao Wou-Ki’s Juin-Octobre 1985, sold for US$65.2 million at Sotheby’s in 2018, the most expensive work of art to go under the hammer in Hong Kong.

According to Sotheby’s Asia chairman Nicolas Chow, who also serves as the auction house’s international head and chairman for Chinese Works of Art, Chinese art continues to be in high demand among collectors from China, the US and Europe. He points to Sotheby’s US$196 million in aggregate sales for Chinese artworks in 2019 as proof. “Buyers are selective and discerning, but the appetite for top quality, rare and fresh masterpieces continues to be there.”

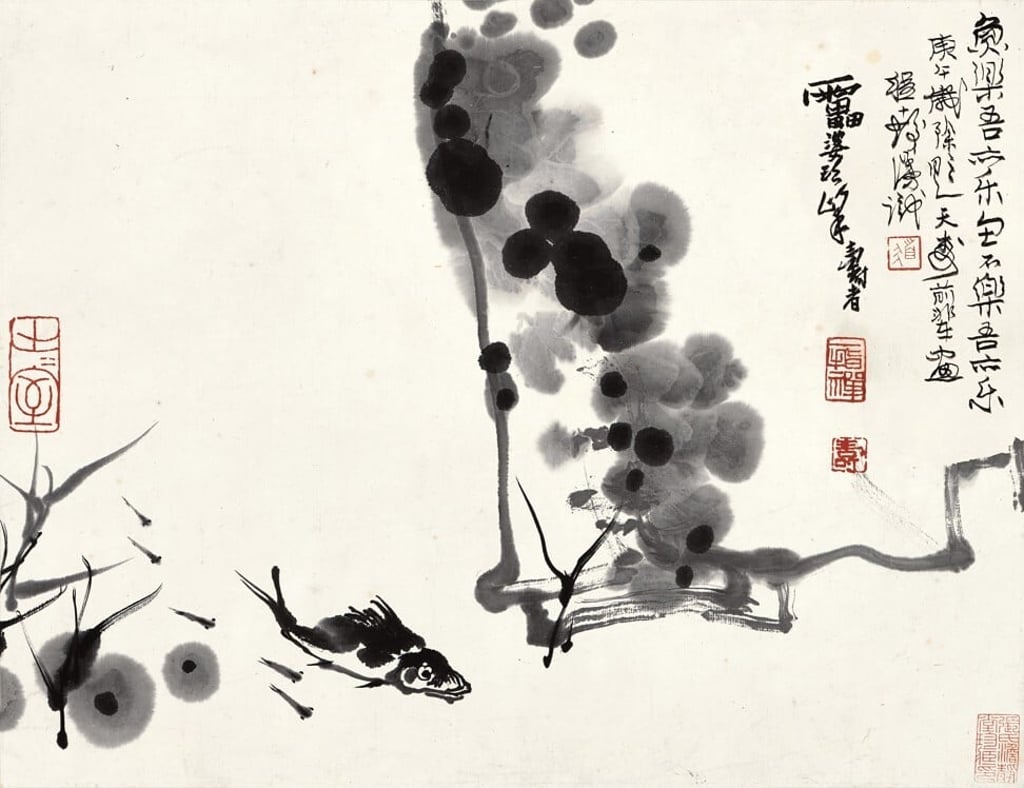

A rising number of these buyers are millennials. “Our latest Contemporary Art Hong Kong Online sale (held in the first half of April) achieved over HK$10 million (US$1.29 million), and almost 50 per cent of the bidders were aged under 40,” says Chow. Aside from being digitally savvy and accustomed to non-traditional bidding methods, these young buyers also “tend to be more eclectic and diverse, going beyond the status quo and supporting artists that align with their personal tastes and styles”. Both interested in art history and exposed to global contemporary art, they’re as likely to buy a Zhang Daqian as a Zao Wou-Ki.

And for some of them, they’re likely to become major players in the art industry as well.