Renowned Robert A.M. Stern Architects’ new landmark Hong Kong project – a luxury residential development on exclusive Kadoorie Hill

- Development of St. George’s Mansions, which will comprise three tower blocks that look out on Argyle Street and Kadoorie Avenue, set to be completed in 2022

- American Robert Stern previously worked on city’s high-class developments including Mount Nicholson, on The Peak, and The Morgan, in Mid-Levels

World renowned American architect Robert Stern has no plans to retire, even after his 81st birthday celebration in May.

Stern, educated at both Columbia and Yale University, who was dean of the Yale School of Architecture from 1998 to 2016 and previously professor of architecture and director of the Historic Preservation Program at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation at Columbia University, is almost as well known for his yellow socks as his work as an architect.

“I always wear my yellow socks. I’ve become famous for my yellow socks, so I can’t not wear my yellow socks,” he told The New York Times in 2015. “Sometimes on the weekend, though, I go crazy and wear blue ones.”

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Stern is best known for his designs of buildings in the US, including the classically styled New York apartment building, 15 Central Park West, two residential colleges at Yale University and the modernist skyscraper, Comcast Center in Philadelphia.

Yet, Stern is no stranger to Hong Kong, having worked on projects including Mount Nicholson, on The Peak, which in 2017 was Asia’s most expensive address, and The Morgan, a luxury high-rise block of flats in Conduit Road, Mid-Levels.

Here he talks about his love of architecture and his thoughts on his plans to revitalise the city’s Kadoorie Hill neighbourhood, in Kowloon.

Who were your main architectural influences?

I was a student [at Yale] when Paul Rudolph [known for his spatially complex, brutalist concrete designs] was chairman of the department of architecture. He was the architect of Hong Kong’s Lippo Centre, [a twin-tower skyscraper complex built in 1988 in Admiralty]. I studied with him long before the Lippo Centre.

But I have had many influences. It’s not a person so much as a category of architectural ideas such as the skyscrapers in the 1920s and ’30s, which I got to know when I was a kid.

I would travel from my family’s apartment in Brooklyn to Manhattan on a Saturday morning and wander around with my parents, or sometimes go there by myself on a Sunday morning, when Wall Street was very quiet, to look at these incredible buildings.

How would you describe your style of architectural design?

I’ve used the phrase “Modern Traditionalist”. I like to look back with my design partners to buildings and ideas from the past, to refresh them in order to go forward. This enables us to fit our buildings into established architectural contexts.

What aesthetic elements are unique to Hong Kong’s buildings?

Most of the buildings are light in colour, which gives the city overall a wonderful quality, especially when the sun is out. Yet even on grey days, you see it glows. It’s like San Francisco, in that sense, which is also a city surrounded by hills.

The density [of the buildings], of course, is unique, too. You have very narrow streets with very tall buildings.

What is special about Kadoorie Hill?

I think it is great that Kadoorie Hill is so well preserved. It’s such a surprise coming upon Kadoorie Hill when you go to Kowloon which is so dense. Then you go to Kadoorie Hill and it’s like Beverly Hills in Los Angeles. It has a spaciousness, a suburban quality, which I think is very pleasant.

Kadoorie Hill is one of the rare places in the modern world where a more human scale, a more intimate relationship with the landscape and trees and so forth, is maintained.

It’s a park with houses in it. A “villa-park”.

What are some key features of the Kadoorie Hill project?

In designing St. George’s Mansions with Grant Marani and Bina Bhattacharyya, my partners at Robert A.M. Stern Architects, we chose limestone for the facades [because it] is a wonderful material and also because it blends well with the coloration of most of the [existing] villas and garden walls on Kadoorie Hill, so it makes the building an extension of Kadoorie Hill.

We’ve done research over the past 10 years or so while working in Hong Kong and we know this kind of limestone, which has this wonderful pinkish tan glow, will work well in this kind of place. It will be very beautiful when the sunlight hits it.

I think nothing is better than stone to pick up the sun, to get shadows around windows and openings. Of course, our building has punched windows – it’s not a wall of glass. So, you have the dark of the windows, the light of the stone: it will have a rhythm to it that many contemporary buildings lack.

Can you tell us more about the design elements of the Kadoorie Hill project?

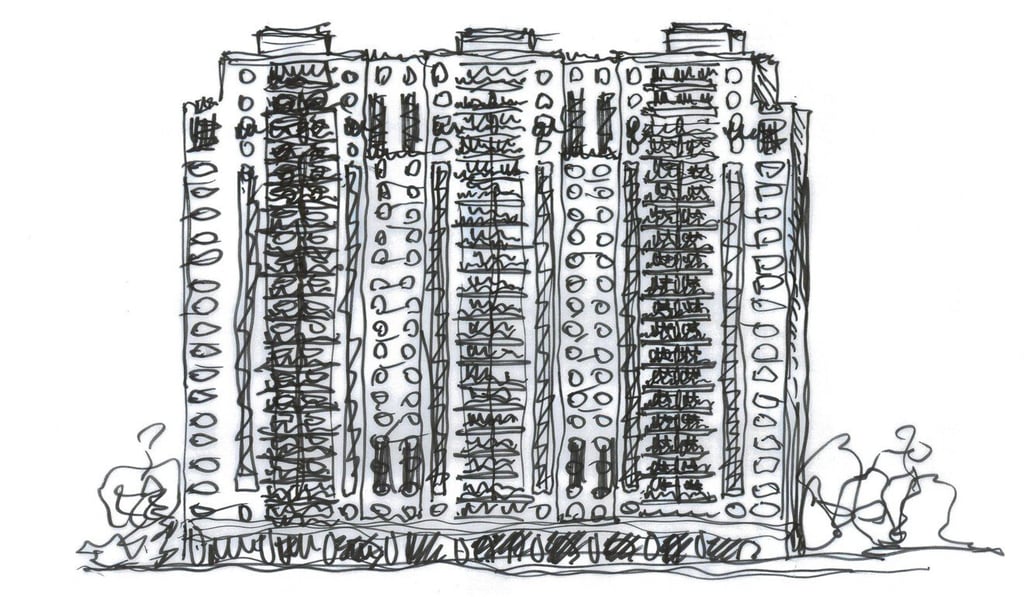

One of our big ideas for St. George’s Mansions was to take a big building and break it up visually into three towers. Another important decision was to make the two principal sides of the building quite different from each other.

Looking out on to Argyle Street, you have the more metropolitan side of the building, which complements the historic CLP tower block, which is quite nice. The other side, looking out on to Kadoorie Avenue, has been designed to blend in with the neighbourhood, and will see people pass through an arrival courtyard area that provides access to parking and leads to the entrance to the development’s three towers.

The bigger apartments are going to be on the Kadoorie Avenue side of the building. I think it will become a landmark building.

What is your favourite part of this project?

Getting it built! I think the towers will be very interesting on the skyline, and also as a kind of backdrop to Kadoorie Hill. But I think also the treatment of the base of the building, on both the Argyle Street side and the Kadoorie Avenue side, will be significant. How we relate to our historic neighbours is a very interesting challenge and it’s a kind of challenge I enjoy.

There’s nothing else that I’m aware of that will rise or has risen to this quality so far. St. George’s Mansions will set a new standard.