- City state has applied to have its beloved hawker scene, which dates back to mid-1800s, recognised on Unesco List of Intangible Cultural Heritage

- Thousands of owners of food stalls – popular with locals and tourists – form Facebook group to promote their businesses during Covid-19 outbreak

For more than three decades, hawker Melvin Chew has been selling traditional Teochew braised duck and kway chap – flat, broad rice noodles in a soup made with dark soy sauce served with a variety of pig innards – at Chinatown Complex Food Centre, located in Singapore’s city centre.

The 42-year-old Singaporean is one of thousands of hawkers who operate stalls in hawker centres around the city state, which are frequented by residents and tourists alike.

“In a hawker centre, you can see all sorts of food,” he says. “You can have Malay food, Indian food and Chinese food – a mass of varieties which you can hardly find in a restaurant.”

Hawker centres – arguably one of the most recognisable symbols of the Lion City’s culture and heritage – are a delight for dedicated foodies and have long served as a melting pot of cuisines for the city’s multiethnic society.

Official records show that there are currently more than 110 markets and hawker centres in Singapore, and authorities are planning to build 20 more.

Chew is a second-generation family hawker working at Jin Ji Teochew Braised Duck & Kway Chap, which originally was an outdoor street stall started by his parents in 1983.

Food culture is very important because the culture [has been] built up by [our] pioneer batch of hawkers, who are our ancestors

He says food stalls in hawker centres serve authentic food because their owners – who come from different ethnic backgrounds – often use family recipes passed down through generations.

“Food culture is very important because the culture [has been] built up by [our] pioneer batch of hawkers, who are our ancestors,” Chew says.

A melting pot of cuisines

Hawker culture has long been an important part of Singaporean life. Singapore’s National Heritage Board says its origins can be traced back to the mid-1800s, when many new settlers sold affordable meals as a way to earn a living.

Numerous food stalls could be found in areas such as Chinatown and Orchard Road, which served the city state’s most popular dishes, such as laksa (spicy rice noodle soup), satay (grilled, skewered meat) and Hainanese chicken rice.

In the two decades after Singapore declared independence in 1965, authorities began resettling street hawkers into newly constructed hawker centres across the island to improve sanitation.

Despite the move, Singapore’s hawker culture has remained vibrant and gained popularity among tourists from around the world.

Rahayu Rahman, 52, who runs a hawker stall selling traditional Malay food with her 73-year-old mother, Aminah Sanwan – known by their customers as “Mama Minah” – says the appeal of the hawker culture lies in its human connection.

“We still like to maintain the originality of Malay food,” she says, adding she has insisted on using old-school recipes and cooking methods to serve classic Malay delicacies, such as lontong (rice cake served in coconut and vegetable stew) and mee rebus (egg noodles in thick spicy gravy).

The mother-daughter duo, who have been running Makan Food Stall in Sembawang Hills Food Centre for 18 years, have built up a close relationship with their customers.

“When they eat our food, they will tell us that the food reminds them of their late mother or late grandmother,” Rahayu says. “I am happy that some customers will order food to share with their families.”

The role of Singapore’s hawker culture in promoting relationships across ethnicities has started to gain greater prominence on the international stage.

In March 2019, Singapore applied to inscribe its hawker culture onto the Unesco List of Intangible Cultural Heritage – a programme that highlights the importance of protecting cultural practices and knowledge around the world.

We still like to maintain the originality of Malay food … when they eat our food, they will tell us that the food reminds them of their late mother or late grandmother

In the submission, authorities said the culture deserved to be recognised because it embodied culinary practices that reflected the city state’s multicultural society.

The result of the application is expected to be announced by the end of this year.

A sense of unity

Despite the efforts to protect their culture, hawkers have been facing challenges to keep their businesses running amid uncertainties caused by the coronavirus disease, Covid-19, pandemic.

In April, Singapore imposed mandatory stay-at-home orders as it worked to combat the spread of the disease in the community.

Chew says he is heartbroken that many veteran hawkers have been forced to leave the industry because of the drop in customer demand.

“I see a lot of brands, which took them 10, 20, or 30 years to build, but just a few months into the pandemic, they had to close down the business,” he says.

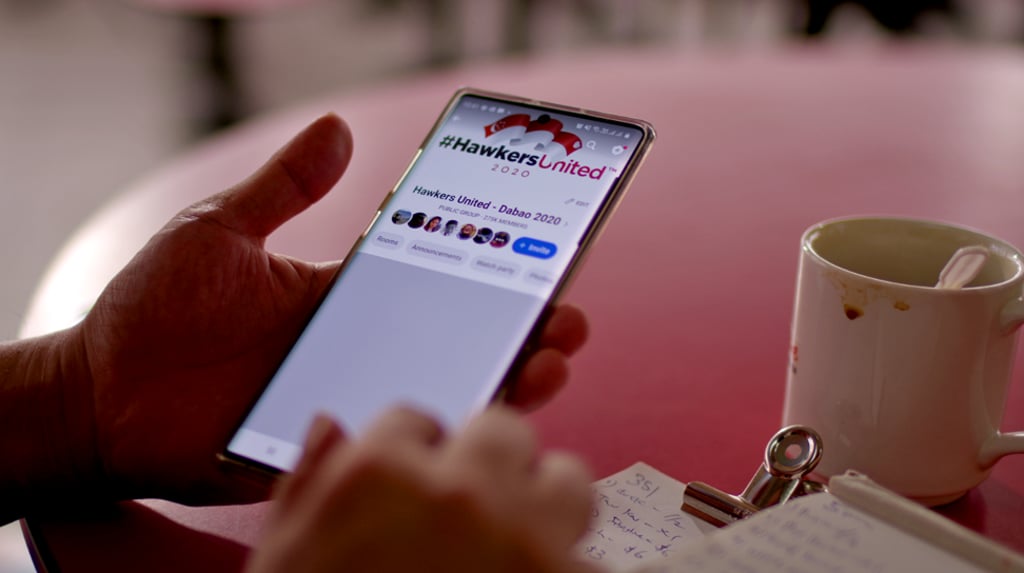

To promote Singapore’s hawker industry, Chew opened a Facebook group called Hawkers United Dabao in early April, when the city state’s authorities announced partial lockdown measures to curb the virus.

The Facebook group, which currently has more than 270,000 members, has enabled hawkers and restaurant owners to tell people about their businesses and delivery options.

There are two things [which] connect people: one is music, and the other is food

“I think Covid-19 started to make hawkers realise that technology is very important, so as we move on, we have to adapt to technology,” Chew says.

At a time when most offices and schools are closed, many users have shared reviews about their favourite hawkers in the Facebook group, thereby earning them new customers.

Chew’s initiative has also benefited the business of Rahayu and her mother.

As most offices are closed, only certain workers can come, Rahayu says. “When they come, they will tell us that they saw the post on Facebook, so they wanted to try our food,” she says.

“Of course, we are very happy and appreciate them very much for coming here.”

Chew says he hopes that as more people realise the importance of the hawker culture in unifying Singapore’s multicultural society, they will work to protect it.

“There are two things [which] connect people: one is music, and the other is food,” he says. “[People] want to support the hawkers, because they love our hawker culture.”

“With or without [the Covid-19] pandemic, hawkers will always do their best. They will always want to serve what they have to their customers.”

Emmeline Ong contributed to this report.