Chinese-born Du Yun’s Pulitzer-winning fantasy opera on human trafficking comes to Hong Kong

Production, focused on dark machinations of human psyche as two angels are exploited after falling to Earth, is part of city’s ninth New Vision Arts Festival

The Shanghai-born composer, multi-instrumentalist, vocalist and performance artist Du Yun is nothing short of a musical maelstrom.

Du, 41, winner of the 2017 Pulitzer prize for music for her opera Angel’s Bone, draws her inspiration from a dizzying range of musical genres – from classical to indie pop, and punk to the music of oral tradition.

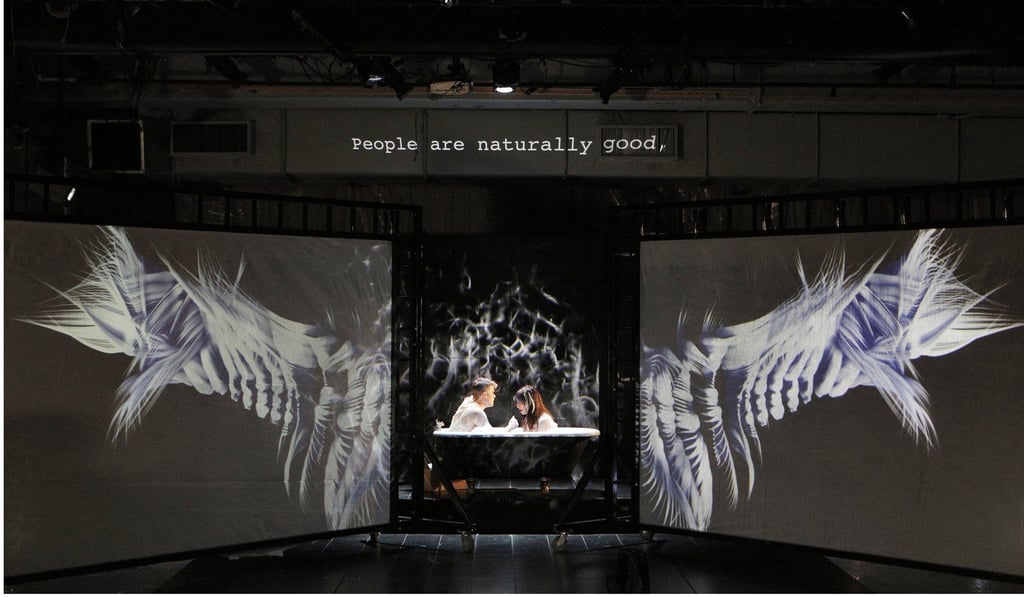

Angel’s Bone, which Hong Kong audiences have the chance to experience on November 10 and 11 at Kwai Tsing Theatre as part of the ninth New Vision Arts Festival – redefines opera, blending chamber music, free-form jazz and theatre with electronica, cabaret, magical realism, punk rock and video art.

The show explores the dark machinations of the human psych through a story of modern-day trafficking when two angels fall to Earth and are held in sexual and spiritual slavery by a suburban couple.

In a downward spiral of greed and moral decay, Mr and Mrs X.E. pimp out these heavenly beings, forcing them to perform perverted acts for money.

Ahead of her Hong Kong performance, we speak to Du about the show, her inspirations and her new project that aims to revitalise Chinese opera.

Human trafficking is not a light topic. Why did you decide to tackle this subject in ‘Angel’s Bone’?

Creating this piece took seven years. I met Royce Vavrek, who wrote the libretto for Angel’s Bone, years ago in New York when he had a work in a new opera showcase.

At first, the story of ‘Angel’s Bone’ was more about angels, but slowly became more about the middlemen ... as human beings, if given the opportunity to exploit, may go to dark places

He had a piece, I had a piece, and we were both taken with each other’s styles. You could say we shared a common taste and aesthetics. We immediately wanted to work together.

He wanted to write about angels, while I was reading a book about prostitution. This book made a big impression on me.

I realised that, even though I’ve not been a victim of human trafficking, I had a preconceived notion of what prostitution and trafficking was about.

But I learned that it’s a very complicated emotional relationship that some of these trafficked girls have with their middleman; some of these young girls refer to them as boyfriends. I was fascinated by this very weighty topic.

At first, the story of Angel’s Bone was more about angels, but it slowly became more about the middlemen – the suburban couple – and especially the wife.

Through her, I could see how I might feel.

I’m not the victim: I don’t pretend I am, and I don’t want to be a spokesperson for the victim. But we, as human beings, if given the opportunity to exploit, may go to dark places.

I can relate to this as a creator, and I think I can be both passionate and objective about it at the same time.

You draw on an unfettered range of musical and artistic genres in your work. Do you do this consciously?

Yes and no. To me, style isn’t very important.

But, in Angel’s Bone, for the Girl Angel’s voice, I used a punk voice very intentionally. Not because I want to revolutionise opera, but because she is singing about a rape scene.

I have to be honest: sometimes I don’t like opera.

In traditional operas, at theatrical, key moments they deliver an aria. But any victim, any girl being raped, would not deliver an aria. Someone would scream or use their voice in a visceral way.

I didn’t think, “I’ll use a punk voice”, but the story needed it to be this way.

I later realised her voice should be like this all the time, although it does start out more ethereal at the beginning of the story.

Some audiences watching your show have said they had to look away at some points in the opera. Was it important to you to not shy away from the darkness of what happens in the story?

There’s no sex on stage, no nudity, no profane language. The sex scenes are implied.

There’s no sex on stage, no nudity, no profane language [in ‘Angel’s Bone’]. The sex scenes are implied. The explicitness comes from brutal reality

The explicitness comes from brutal reality. There are times when the audience gasps, when they get a look into the dark psyche of the neighbours as they abuse the angels.

They see the faces on stage and the music is intense … it’s a heightened emotional atmosphere and here some people look away.

If there was nudity on stage, most people would not look away, certainly not New York audiences – there’s no shock value in nudity.

But people look away in Angel’s Bone as they don’t want to confront their own dark places.

‘Angel’s Bone’ doesn’t offer up a moral lesson. Was this something you deliberately avoided?

Yes. Not offering a moral lesson is not saying it’s OK: there’s a difference.

Not giving a moral lesson is a strong message in itself. The message is more about trying to understand people’s psychs.

Human trafficking is a complicated topic and each region in the world has its own economic and social dynamics.

Not giving a moral lesson [in ‘Angel’s Bone’] is a strong message in itself. The message is more about trying to understand people’s psychs

In some countries, such as in Southeast Asia, parents may sell off their daughters out of desperate poverty.

In Eastern Europe, there are more examples of girls wanting to be models, who then become strip club dancers.

We created Angel’s Bone originally for the Prototype Festival in New York City and we set the story in rural America because I didn’t want the audience thinking that this was a story far away from them.

New York and New Jersey have huge trafficking problems; the Super Bowl is the biggest trafficking event in the US.

In London, there are often cases of runaway teenagers with addiction problems being picked up by human traffickers. So each place has its own motivations and outcomes.

There’s no clear moral story to be learned or offered here.

You’re now working on a project with Chinese traditional music – tell us more about this

I grew up in China and moved to the US when I was 20.

I grew up in China and moved to the US aged 20. There’s always been a Chinese influence in my work, but I have not composed Chinese music or even Chinese-influenced music

There has always been a Chinese influence in my work, but I have not composed Chinese music or even Chinese-influenced music.

Each of my projects has been distinctly different.

But my new initiative in Xinchang [a county to the south of Zhejiang province in mainland China] aims to revamp Chinese opera.

I’ve been following a regional opera troupe since last summer.

I’ve been learning from them and collaborating with them and I want to take Chinese opera to a new direction.

Chinese opera is very traditional.

There’s a new consumerism in China that says we should only produce what the market needs and wants, but I think the people are ready for a new take on opera.

And artists and producers should lead the way.

Western opera is undergoing a transformation, so do you think Chinese opera will, too?

In America and Europe, the new productions are smaller and more mobile, more amplified, and more so-called transdisciplinary. There’s huge investment in making new works.

But in China there is a dire need for original content. While there have been some attempts at modernising Chinese opera, sometimes they are not done as well as they could be.

It’s not about just taking traditional opera and adding beats or lighting. The story and concepts need to be looked at.

Borrowing or mixing styles to me means using style as a condiment and I’m not interested in this.

One of the aspects of Chinese opera that fascinates me is how women would train from a young age to play the parts of men, especially old men, such as a general who is about to die. Why would a woman want to take this role?

I’m interested in studying elements on a molecular level, asking, “What do I need this molecule for? If I blend this material with that material, what will it create?”.

A good artist should aim to advance a genre. We owe it to the history of the genre to take things at a molecular level.

This is a long process, especially in the case of Chinese opera as it has been around so long and knowledge is passed down by oral tradition and not openly shared.

I’m experimenting with new directions for Chinese opera now and talking to foundations about it. If I can do a work on this in the next few years, I’ll be very happy.

One of the aspects of Chinese opera that fascinates me is how women would train from a young age to play the parts of men, especially old men, such as a general who is about to die.

Why would a woman want to take this role? So I’m experimenting with a young woman singing an aria and, as a key catalyst for the scene, she takes off her beard.

So it’s playing with gender roles. I had goosebumps when I saw this on stage. I think it will be very effective.