Switch on to electric vehicles: your A-Z to what BEV, HEV, NEV and REEV all mean

- Governments worldwide want to cut urban pollution levels by banning diesel-fuelled vehicles

- Incentives are being offered to people to switch over to electric-powered vehicles

Global environmental challenges and increased pressure on motoring manufacturers to help create cleaner living conditions are gradually helping to increase the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs).

Electric vehicles are here to stay in Hong Kong – and on the charge

On an international scale, China is leading the charge in EV sales to date. Figures gathered in 2018 show Chinese buyers together bought more than 2.2 million EVs – about 7.6 per cent of all estimated commercial and passenger vehicles bought that year.

Acronym glossary

There has never been a more favourable time to consider the potential of EVs, but you may be wondering where to start. For anyone looking into the market, some of the acronyms, such as BEV, PEV, PHEV and other EV terminology can be daunting.

BEV

A battery electric vehicle (BEV) is an all-electric. Other synonyms include “pure electric vehicle” (not to be confused with PEVs) and “only-electric vehicle”. Classed within the PEV subcategory, BEVs rely solely on the power of an internal battery for energy.

Examples of this type of car include the BMW i models, Renault Zoe, Tesla Model S and the Nissan Leaf.

Last year the Leaf was the most popular EV in the world, selling more than 300,000 units.

The two top-of-the-line BEV models in this list are the Nissan Leaf, with a single-charge range and efficiency of 243km (150 miles), and the Tesla Model S Long Range, of 600km.

Other BEVs include motorcycles currently used for professional racing (Energica Motorcycles and KTM), BYD electric trucks and vans, some railcars, and other public transport such as the autonomous, 3D-printed Olli bus in development at Arizona’s Local Motors.

HEV

Hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) are cars that cannot be recharged using an external power source. The vehicles combine a traditional internal combustion engine with electric battery propulsion.

They are also capable of converting other excess energy, such as kinetic energy from braking, into electric power for internal electronics, such as the radio and dashboard lights.

When stationary, these cars often have a start-stop system, too, further reducing emissions.

The Toyota Prius, which began popularising hybrids in 2007, is one example of this type of EV. Along with the Lexus hybrid family, the Prius keeps Toyota at the top for the chart for the highest number of HEV sales in the world.

Other HEV examples are the Honda Civic Hybrid and Toyota Camry Hybrid.

ICE

ICE is the acronym used within EV markets to denote the use of a traditional internal combustion engine. In hybrid vehicles, an ICE complements an electric battery and recharges it.

NEV

In China, NEV refers to a class of new energy vehicles encompassing both plug-in electric vehicles and HEVs. In the United States, however, NEV is the term given to neighbourhood electric vehicles that have legal limitations to speed limits of no more than 72km/h (45 miles per hour).

PEV

PEV, or plug-in electric vehicle, is a blanket term for a subcategory of EVs that encompasses most of the terms listed below. Hybrid electric vehicles that use an ICE to continually recharge are not classed as PEVs because they cannot be connected to a power supply for charging.

PHEV

The Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV, Chevrolet Volt family and Toyota Prius PHV are top-selling examples of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs). Unlike HEVs, PHEVs can be charged from an external source, although they can also rely on an engine and fuel power.

A PHEV’s range, which relies solely on electric battery power, is often denoted by a number after the PHEV acronym, for example, PHEV32km.

REEV

PHEVs with a series power train – the main components that generate power and deliver it to the road surface – are sometimes referred to as REEVs, or range-extended electric vehicles.

The Chevrolet Volt, Fisker Karma and potentially some Tesla cars can be referred to as REEVs.

Many concept models, such as the Proton Exora and Preve and General Motors’ 2018 REEV, are also classed in this category to differentiate them from typical PHEVs.

Charging EVs

One major issue that EV owners face is charging. All PEVs are compatible with standard electricity outlets and can be charged at home.

The standard cable that comes with the car can be plugged into the mains like any other electronic device. Depending on the equipment, charging a BEV using a home outlet can add 3 to 8km of range per hour on a Level 1 Electric Vehicle Service Equipment (EVSE) or 16 to 96km per hour on a Level 2 EVSE. For instance, a 2019 Nissan Leaf with a 40kWh battery can be fully charged in 8 hours on a Level 2 charger.

After a full charge though, users typically “top up” their cars when not in use and rarely have to do a full charge in a single session. For PHEVs, charging times are a lot shorter using these chargers, typically taking between two and four hours.

For faster charging rates, EV owners can invest in a separate power unit. By comparison, these specially installed units can charge between three and seven times faster than a standard home outlet.

Many companies, including Nissan, Peugeot and Tesla, have developed their own home power units for EVs.

One of the first advances the EV industry has made for on-the-go drivers is fast charging, which allows the replenishing of EV batteries by up to 80 per cent after 30 to 60 minutes of charge

Once set up, home charging is simple and effective. However, challenges arise when drivers are taking a long-distance journey or stay away from home for a number of days.

This is where further technological development comes in. One of the first advances the EV industry has made for on-the-go drivers is fast charging.

What is fast charging?

Fast charging solutions are capable of replenishing EV batteries by up to 80 per cent after 30 to 60 minutes of charge. Sometimes also known as rapid charging, the power provided by these units is typically 43kW or 50kW, although there are no industry standards at this point.

Tesla has developed Superchargers for its own vehicles capable only of charging at around 120kW. Fast charging is available only at selected stations and it is not compatible with all PEVs.

Fast charging cars compatible with up to a standard 50kW fast charger include the Nissan Leaf and Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV.

Essential apps for EV owners

Although many EV charging options are available, infrastructural development still does not fully support the change from ICE. But some of the challenges drivers currently experience are being eased by specially created apps.

Still in its early stages, EV app development focuses generally on helping drivers locate available charging stations for their cars.

The availability of these apps varies between countries, and sometimes by car brand: Tesla, for example, has its own branded charging stations.

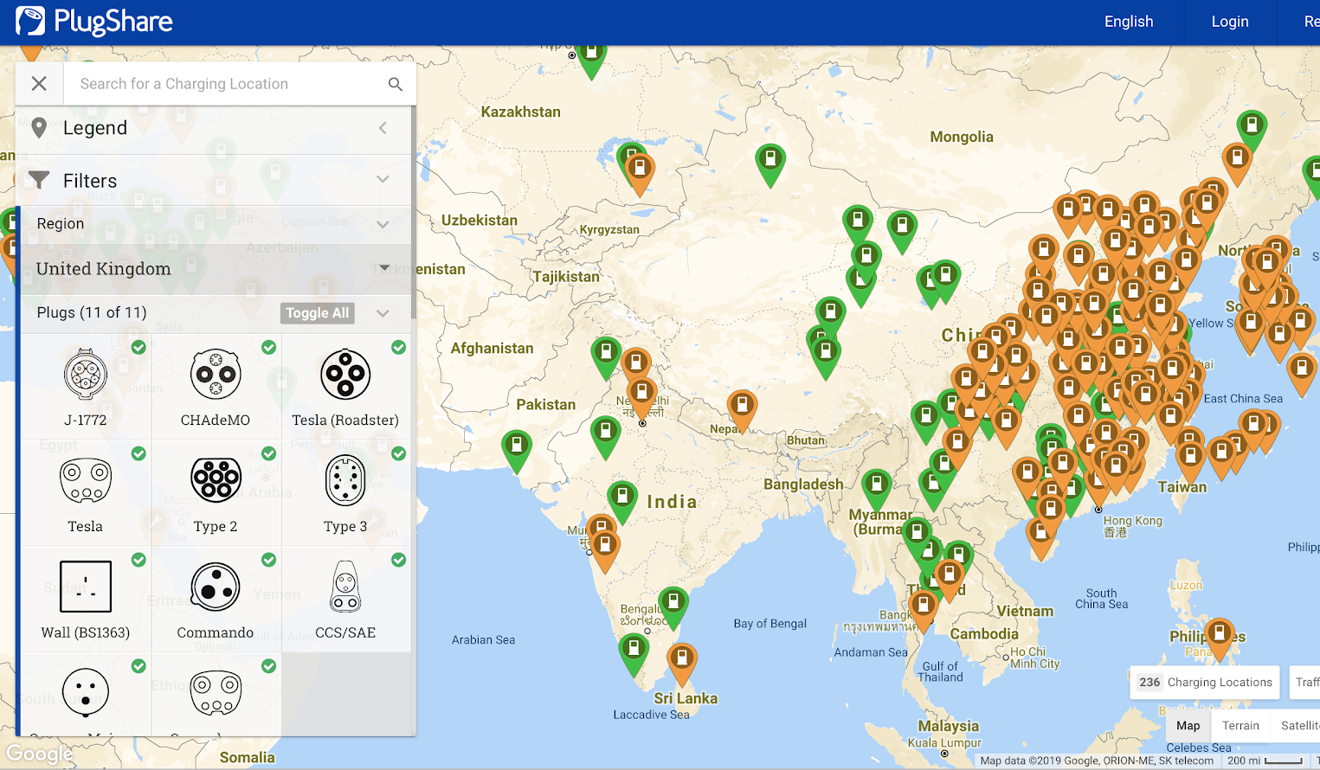

PlugShare is one example of an app working hard to map the local and international network of charging stations. With this app, drivers can make their own home chargers available for use by the EV community, or they can submit data about a public station.

Some apps have also been developed to help EV drivers pay for their charge when using a public station, but there is still a gap in the market for more innovative solutions.

Gradually, a variety of smart charging apps are emerging. The concept behind these apps is that they use power grid data to determine the most green and efficient period to charge an EV within a user-selected time slot.

The apps take into account values such as the available power grid capacity, availability of sustainable energy, and the price of energy within the set time frame to create cost and emissions savings for the customer.

In the Netherlands, Jedlix has developed a smart charging app of this type that also gives users a small reward of 2 cents per kWh when using it.

In the UK, the independent energy supplier, Igloo Energy, has also developed a smart charging app now on trial for Tesla users. Igloo’s app is reportedly capable of reducing EV emissions by up to 20 per cent.

A great deal of research is being carried out to increase the capacity of electric batteries themselves and help vehicles go farther on a single charge

Beyond applications, a great deal of research is being carried out to increase the capacity of electric batteries themselves and help vehicles go farther on a single charge.

Innolith Science and Technology, a Swiss start-up company, is developing an alternative battery with an energy density of 1,000Wh/kg (or Watt hour per kg) – about four times the density of Tesla car batteries.

The secret to Innolith’s technology is a platform based on inorganic electrolyte, instead of traditional Li-Ion, batteries, as used by Tesla and in many common rechargeable devices.

Another aim of the projects such as Innolith’s is to reduce the cost of EV batteries, which will be essential for reducing the cost of the cars and encouraging more consumers to use them.

Autonomous and autopilot functionality are also being considered by the industry. Recently Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla, said that his company would be introducing driverless taxis on roads by the end of 2020.

Around the world, legislation is changing to reduce pollution within urban environments and some governments have even set targets to eliminate at least diesel-fuelled ICE vehicles from the road over the next 11 years.

In response, many of these same bodies are offering financial incentives to help their populations make the switch to EV technology.

Although other solutions are necessary to widen the use of EV, making an EV your car of choice could be a shrewd and secure move for the future.