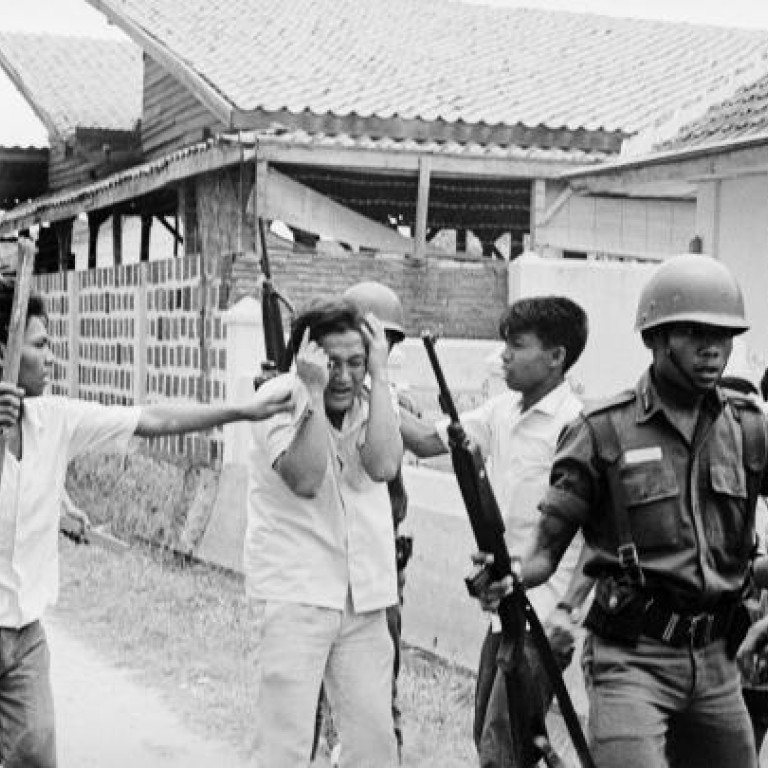

Victims of 1960s communist purges in Indonesia still wait for an apology

Atrocities against suspected communists in Indonesia in the 1960s are finally being addressed, but it is a painfully slow process

At 72, Sri Sulistyawati still remembers the day when two Indonesian soldiers placed a wooden plank across her belly and used her body as a see-saw, before she fainted from the pain.

Her tale is a lost footnote in one of the last century's bloodiest atrocities, when between 500,000 and two million suspected communists were killed in purges in 1965 and 1966 under Suharto, a general who was toppled in 1998.

After being swept under the carpet for nearly 50 years, those atrocities were this year acknowledged for the first time by the government's own human rights body, providing some solace to victims whose pain and disgrace have gone ignored for decades.

In an unprecedented move, Indonesia's official human rights body Komnas HAM said in July that it had found evidence of widespread gross human rights violations nationwide during the purges. The report, based on a three-year inquiry and the testimony of 349 witnesses, urged that military officers be tried for crimes including murder, extermination, slavery, forced eviction, torture and mass rape.

The report demanded the government issue an apology and compensate victims and families - a move it said it intended to make despite resistance from retired military commanders and the nation's largest Muslim body.

Sri lives in a two-storey nursing home in Jakarta with a dozen other survivors, mostly women aged between 70 to 90. "They tied my arms and legs with a rope and dragged me on the ground with my face down for a kilometre to a military post," said Sri, whose crime was being a journalist for a newspaper that backed the country's first president, Sukarno.

"Two soldiers put a wooden plank on my belly, then got on each end and used my body as a see-saw," she remembered. "I fainted from the unbearable pain and had internal bleeding."

The purge had its roots in the tense cold war politics that marked the final years of the reign of Suharto's charismatic predecessor Sukarno.

He fostered the outlawed Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) as a political force to balance the power of mass religious groups and pro-Western generals. This delicate balance collapsed in September 1965, with an abortive coup, blamed on the PKI. Some historians say the military orchestrated the putsch to tighten its grip on power and wipe out communism.

After enduring four years of torture in detention that included electric shocks and nail-pulling for an alleged communist link, in 1969 Lukas Tumiso, now 73, landed in a prison labour camp on remote Buru island in eastern Indonesia. He would stay there for 10 years, together with 10,000 other prisoners.

One survivor of the purge said he was jailed with hundreds of other prisoners in a cramped 5 metre by 25-metre room on an island. "It was a place where prisoners were slowly killed. Many only survived for a few months. About a dozen died every night."

For victims such as Sri, a formal apology would provide some solace, even if it comes decades late. "People must know that we were innocent. We did nothing wrong. We are not human garbage," she said.

Presidential adviser Albert Hasibuan said in April that President Dr Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono intended to make an apology to families and victims of past human rights abuses before his second term ends in 2014.

But retired military chiefs and the country's largest Muslim body Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), which has been allegedly implicated in the purges, have rejected the need for any apology. "We can forgive them but we cannot forget," said NU deputy chairman Asad Said Ali. "For us, this is a non-negotiable price: no apology or compensation."