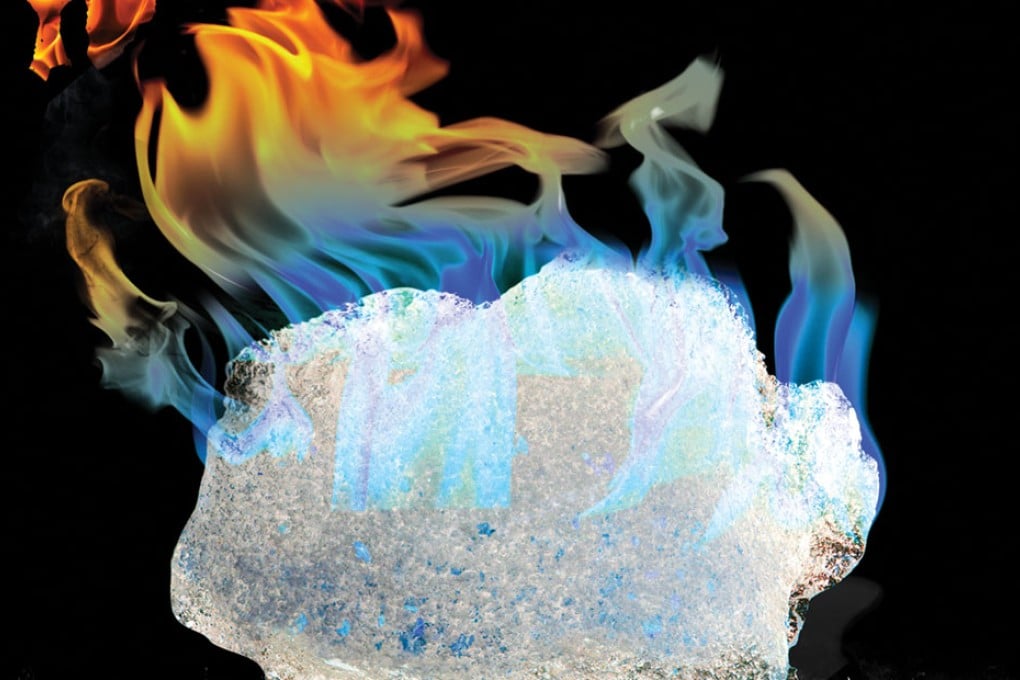

Could 'fire ice' fuel the future?

Japan is aiming to tap potentially vast natural gas reserves trapped beneath the sea floor - including disputed territory claimed by Beijing

During their three-day meeting last month, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe again asked US President Barack Obama to speed up exports of American natural gas to help his beleaguered and energy-poor economy. But the big energy revolution that could ride to Tokyo's rescue may not come on tankers from US ports, but rather from deep underneath the sandy seabed off Japan's own shores.

Other Asian countries facing an energy crunch, including South Korea, India and China, are also hoping to tap into the apparently abundant reserves of methane hydrates, also known as "fire ice." That could help fuel growing economies - but it could also fuel further tensions in regional seas that are already the stage for geopolitical sabre rattling and brinkmanship over natural resources.

Totally unknown until the 1960s, methane hydrates could theoretically store more gas than all the world's conventional gas fields today. The amount that scientists estimate should be obtainable comes to about 43,000 trillion cubic feet, or nearly double the 22,800 trillion cubic feet of technically recoverable traditional natural gas resources around the world. The United States consumed 26 trillion cubic feet of gas last year.

That raises the possibility of an energy revolution that could dwarf even the shale gale that has transformed America's fortunes in a few short years. It could also potentially have big implications for countries, including the US, Australia, Qatar and even Russia, which are banking on unbridled growth in the global trade of liquefied natural gas. The trick will be to figure out exactly how to profitably tap vast deposits of the stuff buried inside the sea floor.